I have just finished correcting the manuscript of my next book, which tells the story of the Catholic intellectual tradition in the twentieth century and will appear in the fall (of which, more very soon). One of the things that struck me, as I went through its large number of pages – much larger than I’ve ever put into a single book before – after some time away from the material, is how often some of the greatest names in recent Catholic life came to the Church because it was either Catholicism or suicide.

Thereby hangs a lesson. Perhaps several. Certainly one large one.

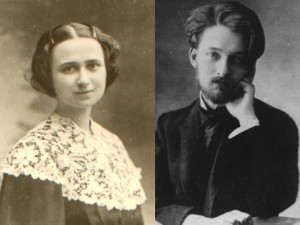

Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, for example, were science students at the Sorbonne at the beginning of the twentieth century. They found science an interesting and worthy discipline, but they soon realized that if the world was only what science said it was at the time – ever-changing configurations of matter and energy – then life was not worth living. They swore a mutual suicide pact, to be consummated if they couldn’t find some reason to live. Thank God they did, or the world would have been deprived of one of the most creative Thomist philosophers in Jacques, and a valuable spiritual writer and poet in Raïssa.

About twenty years later, Evelyn Waugh left Oxford without a degree and had to take a job teaching in a prep school to make ends meet. (You can get a drop-dead funny version of what that meant in his first novel, Decline and Fall.) The teaching job didn’t work out, and another job with C.K. Scott Moncrieff, a Catholic convert who was the translator of Marcel Proust into English, didn’t either. Waugh seems to have decided to do away with himself by swimming out to sea, but was prevented by a swarm of stinging jellyfish. He returned to shore – and to delivering well-placed stings of his own. But also turned to the Church, thanks to conversations he had with the famous convert-maker Fr. Martin D’Arcy, S.J. of Farm Street Church in London.

Fr. D’Arcy was so well known in his day that in the first pages of her novel The Girls of Slender Means Muriel Spark (another convert) presents a character who – bewildered by modern life, as many people were in the twentieth century and still are today – confesses that things had come to such a critical pass that he could “never make up his mind between suicide and an equally drastic course of action known as Father D’Arcy.”

Muriel Spark was a protégé of Graham Greene’s, an even more complex figure who wrote profound novels about sin and salvation (if you haven’t already, look into The Power and the Glory, The End of the Affair, The Heart of the Matter, A Burnt Out Case). But Greene was so bored with ordinary life that he used to play Russian roulette as a young man, and risked death in various hellholes later. Even conversion to Catholicism only kept him, at least in his great period, just this side of what he called “the dangerous edge of things.”

It would be easy to go on at greater length, but the point is clear. An awful lot of highly intelligent and cultivated people not that long ago believed that their decisions about Faith were life-and-death decisions. Literally. As in: I will blow my brains out or jump off a bridge or take poison unless there’s something more to this life – or at least to my life. And they weren’t about to accept mere happy talk. They wanted something that was real and could stand up to real challenges.

I imagine that still happens often today, though it seems to me we’re hearing about it less. What we do hear about – usually only in small Catholic publications – are people who have turned to the Church because they discovered that only the Church is defending some moral position like the indissolubility of marriage or the sanctity of life in the womb, or the truth of Scripture.

There’s nothing wrong, of course, and a great deal right with recognizing the Church as a truth-telling institution. And in a time like ours where “What is truth?” is a rhetorical question not only for cynical politicians, but for large segments of the population, specific truths may themselves be a kind of vehicle for larger revelations.

But we do not live by moral theology alone – indeed are often caught up in passions and problems far beyond ordinary daily life. It seems we may be losing those larger dimensions of Faith because we’ve lost the larger dimensions of lack of Faith.

It’s odd because the secular culture is awash in stories of people lost in drugs, alcohol, sexual problems, aimlessness. Some, we’re told, “find Jesus” or in Twelve-Step-Programs turn to “a higher power.” Those remedies, partial though they be, are at least something. The storms that hit people’s lives are like the high winds that strip away the dead branches from trees. What remains is purer, more evidently alive, less weighed down by dead-ends. And potentially more open to greater truth.

What I’m trying to suggest, however, is that something more, what John Paul II called a use of reason of “truly metaphysical reach,” has to be behind it all – as the Maritains and some of the others I’ve mentioned found – or Christianity is only a twelve-step program or a therapy or a philanthropy. In other words, there’s an ultimate question behind all the penultimate ones. And that question needs to be answered to keep the intermediate and partial answers from becoming what, the great spiritual writers warn us, may be yet another way of refusing the way, the truth, and the life.