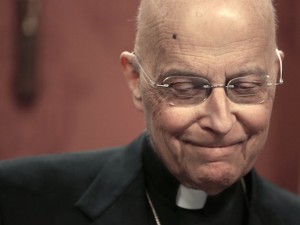

Francis George – retired cardinal archbishop of Chicago, former vicar general of the worldwide Oblates of Mary Immaculate, and past president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (2008-10) – died yesterday morning. It would be hard to praise, even to list, his many gifts and achievements, as a churchman and as a man.

I spent a fair amount of time with him between 2008 and 2011, helping with his books: The Difference God Makes and God in Action. But to be clear: there has probably never been an American bishop less in need of “help” with a book. In the obituaries, he’s being called the “American Ratzinger.” There are several important ways in which that’s true.

He had a remarkable intellect and applied it to a wide variety of subjects. All he really needed was someone to organize production of the books. Thomas Levergood, director of the Lumen Christi Institute at the University of Chicago, had the crucial insight: we should gather the material – mostly chapter-length lectures that the cardinal had given over the years – and schedule a series of meetings on the cardinal’s “free” days for editing and re-writing.

Like Ratzinger, the cardinal had such a fertile and dynamic mind that it was quite something to work with him. Usually, in editing, you cut repetitions, clarify murky passages. Most of the time, this means shortening and sharpening because the language is vague or meandering. With Cardinal George, that almost never happened. When you drew attention to a problem – and you had to be careful because you were inviting the sequel – it almost always meant that he would take another shot, meaning he’d have a half dozen further thoughts at each point. Good thoughts.

He would wander down to the university or over to the Mundelein Seminary to comment on papers by figures like the bioethicist Leon Kass or the French philosopher Jean-Luc Marion. And contrary to what many thought about him, he was quite an extrovert: he loved conversation. Some of his best ideas came from interacting with others.

He didn’t have an easy path to the Chicago see and it wasn’t easy for him being there. He was born in Chicago, but had polio as a child, which left him with a limp. He didn’t let it hamper him much. But I recall, maybe ten years ago, when we were walking to a board meeting at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, he took a hard fall on an icy sidewalk. It shook up the rest of us; he took it in stride.

There were academic obstacles. He studied theology at a seminary in Ottawa, and philosophy at the Catholic University of America. But when the OMI’s assigned him to Louisiana as a young priest, he wanted to do a PhD in philosophy during his “free” time. As he often told it, the department there first rejected him because, it said, Catholic priests, being subject to Church authority, couldn’t really “do” philosophy. He convinced them that was not so. But they imposed a condition: he couldn’t wear priestly garb in class.

Ironically, he wanted to study American philosophy. He’d received a solid foundation in the usual Catholic thought – Plato and Augustine, Aristotle and Aquinas – but he wanted to know what there was to American philosophical figures – Dewey, Royce, James, etc. – and what it meant for the Church in the United States.

Later, he did another doctorate at the Urbaniana University in Rome on inculturation of the Gospel, a useful subject for the head of a global missionary order, but also for someone who wanted to think deeply about how the Church could evangelize American culture.

Chicago was a tough town for him, not only because his theology and morals were traditional and vigorously defended. As a native Chicagoan, he used to laugh telling about meeting Cardinal Bernardin (at one point probably the most prominent member of the American hierarchy) casually at a reception. Not thinking he would ever return to Chicago, he asked Bernardin:

“Joe, how do you govern a place like Chicago?”

Bernardin started laughing: “Govern? Govern? You can’t govern a place like Chicago because it’s by nature ungovernable.”

This from a “liberal” Church leader.

Cardinal George was traditional in faith and morals, but contrary to what many people believe, not particularly conservative in political terms. He disagreed, at times, with articles we ran on this site about immigration. He thought the Church and American society should be welcoming of the stranger among us.

I also tried to get him just to raise the question among his brother bishops, when he was USCCB president, of what could happen once the modern state took complete charge of American medicine via Obamacare. He understood, of course, but like the U.S. bishops for almost a century, he favored universal medical coverage despite the risks.

None of this, of course, won him any good will in the heavily Democratic milieu of Chicago – and Illinois. When he just mentioned in passing, at a conference, that it was an embarrassment that Notre Dame had decided to give President Obama an honorary degree, William Daley (of the Chicago Daleys and later White House chief of staff) absurdly attacked him for “dividing the Church.” And then there was Illinois Senator Dick Durbin, another troublesome Catholic, of whom the less said the better.

He recognized the personal charisma of Barak Obama and spoke of it, but also described the president’s habit of summing up a meeting by saying, “Well, then, we’re agreed,” when in fact they were not.

Among other talents, Cardinal George was a good pianist. I like to play myself and one day, at the piano in the residence, I asked why he didn’t play anymore: “I don’t have the time, and my taste now has outrun my ability.”

If true, it’s one of the few areas in which his talents fell below his very high standards. He was a great leader, a great mind, a great friend. Probably the remark he will be most remembered for is: “I expect to die in my bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square. His successor will pick up the shards of the ruined society and slowly help rebuild civilization as the Church has done so often in human history.”

I’ve been receiving messages from friends, here and abroad, about their affection for him and worries about what happens next for the Church in America. All that is, of course, uncertain, and Cardinal George – who did much in life for both the Church and the nation – would likely say: that, now, depends on us.

Requiescat in pace. Et in paradisum deducant te Angeli; in tuo adventu suscipiant te martyres, et perducant te in civitatem sanctam Ierusalem.