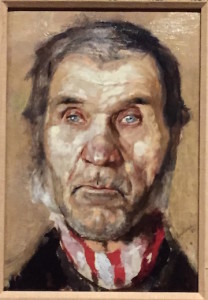

I had just turned from one face when my eyes fell upon another. The first face was that of a poor peasant gentleman (“Study for a Portrait of an Old Man”) painted by the great Norwegian artist Edvard Munch nearly two decades before his most famous work, “The Scream.”

I was privileged to be walking with my wife and a good friend through the wonderful exhibit on Munch and Van Gogh in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. One feature that stands out immediately about the early work of both of these great artists is their interest in the lives and faces of simple peasants, such as the one pictured here.

But as I turned from Munch’s poor, old peasant gentleman, my eyes did not light upon the famous angst-ridden face of “The Scream” – that would come later. Instead I saw a face even more amazing, given where I was. It was the pure, simple face of a teenage boy with Down syndrome, staring up at these wonderful paintings in awe and wonder just like the rest of us, in a country and among so many people who would have assumed that he didn’t possess a sufficient “quality of life” to exist at all.

Standing before me, not far from the house where Anne Frank hid from her persecutors because she was considered “genetically impure,” was a young man whose supposed “genetic impurity” has marked those of his type for extermination.

We all know that children with Down syndrome have that particular look. It’s more identifiable than being Jewish. How many of the artistically sensitive folks walking through this Dutch museum, one has to wonder, would be likely to act upon the desire not to have to look upon that face or faces like it? Some 92 percent of children with Down syndrome are currently aborted. Some have predicted that if current trends continue, Denmark, for example, may see its last child with Down syndrome by 2030.

What were these devoted Dutch aesthetes thinking when they saw this plain, simple face in their midst? What would have prepared them for this sight in a nation that had long ago lost its grounding in a culture that mattered – a culture that used to value in a special way, in its greatest art, the lives of the poor and dispossessed?

More important to me in that moment, however, was what my friend was thinking, since he and I caught sight of the young man with Down syndrome at roughly the same time. For my friend, you see, has a son with Down syndrome, and like any parent, I knew he would be even more sensitive to and protective of this particular child. He would have seen those distressed, disapproving looks a thousand times before, and I knew that at that moment he would want to scream.

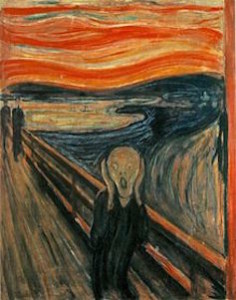

Munch once described the original inspiration for “The Scream” in the following way:

I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.

Genetically unfit? Or God’s beloved?

The original drawing and subsequent paintings Munch produced based on it are widely taken to represent the angst and anxiety of a modern world stripped of its moorings in faith and tradition.

People once thought they could replace “religion” with the spirituality of art. You would have thought that the Holocaust should have done away with any such foolishness. Great art was prominently displayed in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam barely a fifteen-minute walk away from where Anne Frank and her family were hiding in the secret annex during those dark years of World War II. And now we find ourselves once again defending the lives of the “genetically impure” against the ravages of the barbarian elite who style themselves as great doyennes of culture.

Those who are ignorant of history are doomed to repeat it. And too often even those who know history refuse to allow themselves to be judged or warned by it. “We’re not Nazis, after all,” people say, as though our aspirations should rise no higher than that.

When we start seeing “great artists” once again looking for the face of Christ in the faces of the poor and in the faces of children with Down syndrome rather than expending all their energy on their sexual libido, we’ll have a culture of art worth paying attention to again. Until then, it will be mostly more of the same self-indulgent artistic masturbation.

Above: $120,000,000 Below: Priceless

A culture should be judged on how much it values and how well it takes care of the weakest members of society, not on how much money it spends on its paintings and museums. Ours is a culture in which the 1895 pastel-on-board version of the painting, pictured here, sold at Sotheby’s in London on 2 May 2012 for a record price of nearly $120 million. It is also one in which 92 percent of children with Down syndrome are aborted. We’re not Nazis. But no decent person in a hundred years will look back upon this period with any sense of pride.

If Pope Francis is looking to set up a “field hospital” in the midst of a raging battle, then he need not look much further than the killing fields of Europe and America. It is as useless to ask a seriously injured culture whether its carbon offsets are in order as it is to ask a seriously wounded person lying on a battlefield whether he has high cholesterol. Protect the children first. Then we can talk about everything else.