“Drink from the spring and wash in it,” said the beautiful Lady. At her command Bernadette Soubirous, the little shepherdess of Lourdes, looked around for a spring. There wasn’t one. So she scratched at the loose gravel. Then from the murky water that appeared she first drank and then washed her face. She must have looked ridiculous. But in the following days the puddle became running water and then a stream. Since that day in 1858 countless pilgrims have bathed in and been healed by the waters of that spring. These waters and their healing power (sixty-nine documented miracles) are some of the most immediate and enduring fruits of our Lady’s appearance at Lourdes.

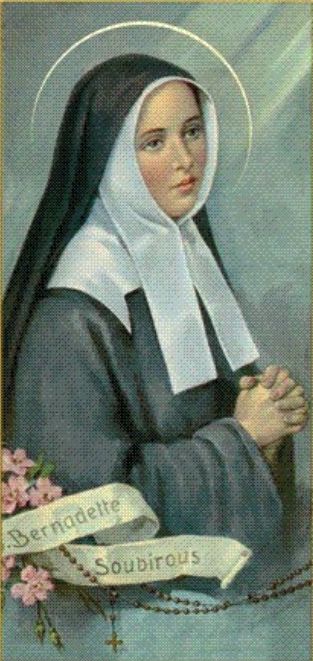

So it is somewhat ironic that we observe the World Day of the Sick today, on the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes. After all, her apparitions are more renowned for healing than sickness! Likewise, there is an irony in the fact that Bernadette herself never benefitted from the healing waters she had uncovered. Always a sickly child, she was prevented from entering the Carmelites because of her weakness. Becoming a Sister of Charity instead, she died of tuberculosis at the young age of thirty-five. Nevertheless, the observation of the World Day of the Sick is well placed. Our Lady of Lourdes teaches – and Bernadette understood clearly – three lessons for the sick: presence, healing, and sacrifice.

First, presence. The first thing to note about our Lady’s appearance at Lourdes is that she appeared. She was present to that ignorant, poor shepherd girl who considered herself so unworthy of the visitor that she dared not call her Mary but always “the beautiful lady.” In the first apparition, nothing was said. Just Mary’s presence – a loving smile, an approving look. Likewise in other apparitions, either little or nothing was said. Presence was enough. Our Lady’s appearance in Lourdes is in the pattern of her Son’s public ministry. The solicitude she shows by her presence reflects that of her Son. He always gravitated towards the suffering – the blind, the lame, the sick, and so on.

The sick suffer not only physically but also emotionally, in the thought that they have been forgotten, become useless or, worse, a burden. We all like visitors when we are sick. We welcome that reminder that we are not alone, forgotten, or a burden. Likewise, we visit the sick – yes, to do good things for them, as we are able – but also to assure them of our love by our presence. His simple presence gave expression of that divine solicitude and care. Our Lady’s visit reminds us of that – and that we need to extend it.

Second, healing. In Lourdes’s miraculous spring, our Lady reminds us of her Son’s healing power. Saint Luke wrote of Him: “Everyone in the crowd sought to touch him because power came forth from him and healed them all.” (Lk 6:19) That healing power continues to break into the world. Not every instance of healing is cataloged as a miracle or announced to the world. But every one of us can point to some recovery or healing that requires more than man’s medicine to explain. Jesus continues to work little miracles of healing still. And He does so for the same reason as back then: not to entertain, not merely to astound, but to show that the kingdom of God has come upon the world.

Third, sacrifice. Our Lord did not heal everyone. Not everyone who prays for healing receives it. Not every visitor to Lourdes departs cured. This brings us to what are in many ways our Lord’s greater gift and more profound miracle: the ability to suffer with Him – that is, to sacrifice.

Suffering is not optional in a fallen world. In our fallen human nature, the body tends inevitably toward death and the sufferings that announce it. Everyone suffers. How we respond to our suffering makes all the difference. We can and should use the natural, medical means at our disposal to bring about some cure and relieve our suffering. But we know that those are limited and cannot grant perfect or permanent relief.

Everyone suffers. But not everyone sacrifices. Suffering is the simple experience of physical illness, injury, disease, and so on. We all encounter that. Sacrifice, on the other hand, is the offering of this suffering in union with Christ. Saint Paul was the first to articulate this theology of suffering: “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ on behalf of his body, which is the church.” (Col 1:24)

What has come to be called “redemptive suffering” begins with the awareness that Christ suffered first and most of all, that all our suffering must be seen in light of His. Then we recall that He is present to us in our suffering such that He shares our suffering and we share His. He is not a mere observer but has drawn close, taken our suffering upon Himself, and remains with us in the midst of it. Finally, our suffering becomes a sacrifice when, conscious of this union with Him, we offer it to Him.

As Saint Paul told the Colossians that he offered his sufferings “for your sake,” so also we should offer ours for specific intentions. As He hung upon the Cross, enduring the extreme of suffering, our Lord saw each and every one of us. . . every struggle. . . every wound. . .every hurt. . . .every need. . .and He offered His sufferings for us. Attaching to our offering a particular person, group, or situation helps to give meaning to our suffering and to unite it more perfectly to His. When we do so our suffering ceases to be merely that and becomes through, with, and in Christ an offering to the Father.