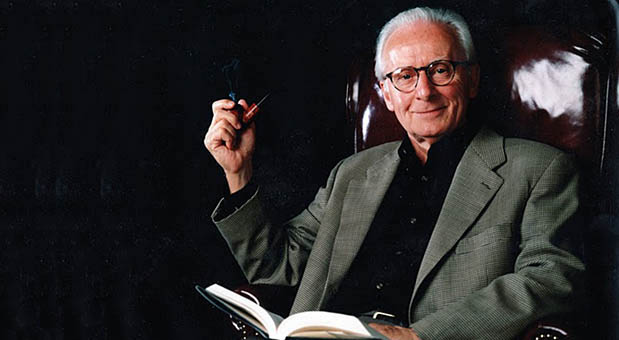

In his book Adventures in Philosophy at Notre Dame, Kenneth Sayre chronicles his philosophy department’s change from scholasticism, to pluralism, to professionalism. In his telling, the bad old days of Thomism, represented by the punny but dogmatic Ralph McInerny, gave way to the golden years of vibrant pluralism, its chief advocate found in the charismatic and farsighted priest Ernan McMullin.

Finally, in pursuit of higher rankings, the department embraced a sterile professionalism, after which came a loss of Catholic identity in faculty and course offerings, trouble recruiting and retaining distinguished faculty, and a drop in rankings. Some aspects of Sayre’s book are informative, persuasive, and constructive. Unfortunately, Sayre also frequently misfires, especially when aiming at longtime ND philosopher (and TCT founder) Ralph McInerny.

According to Sayre, “Ralph at first seemed to take the Council in stride. By the end of. . .[the 1960s], however, his attitude toward Vatican II began to change dramatically. A distinctly negative attitude prevails in his What Went Wrong with Vatican II: The Catholic Crisis Explained.” In fact, Ralph thought so highly of the Council that he led a nighttime series of evening seminars for students (in addition to his normal teaching load) on the documents of Vatican II. Ralph supported the Council; he opposed fanciful interpretations of the Council. His book would be more accurately entitled, What Went Wrong After But Not Because of Vatican II.

In accounting for McInerny’s Thomism, Sayre writes, “The popes had spoken and Ralph obeyed. Obedience to ecclesiastical authority was ingrained in his very nature.” But as one of McInerny’s columns in the Wall Street Journal about the death penalty made clear, Ralph did not simply adopt as wisdom whatever the pope said. After immersion in secular philosophy when getting his M.A. at the University of Minnesota, Ralph’s considered judgment was that Thomism is rationally superior to its rivals.

Sayre writes, “Ralph’s uncompromising opposition to any form of modernity remained a force in the department until the year of his death (2010).” Odd then, that McInerny regularly offered a course with a sympathetic take on John Henry Newman (d. 1890) and Soren Kierkegaard (d.1855), neither of whom is any kind of Thomist. Ralph also chose to participate in a faculty reading group discussing philosophers such as Strawson, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Husserl, and Wittgenstein.

When Ralph organized the Perspective Series in 1967-68, he invited one Thomist, Joseph Pieper, and three representatives of modern philosophy. Even a casual reading of McInerny’s Characters in Search of their Author, the book that came out of his presentation of the prestigious Gifford Lectures, reveals an appreciative engagement with modern and contemporary figures of all kinds.

Sayre’s continues, “As far as traditionalists like Ralph McInerny and Herman Reith were concerned, being a Catholic philosopher was tantamount to being a Thomist.” In fact, Ralph respected that other Catholic philosophers took their lead from figures such as Augustine, Scotus, Newman, and Husserl. Ralph greatly admired Catholic thinkers, such as Joseph Ratzinger, who did not share his appreciation of Aquinas.

Sayre consistently casts not just his beliefs but Ralph’s actions in an unflattering light, “in later years Ralph devoted less and less time to his academic duties.” Allegedly, Ralph didn’t pull his fair weight with the students. “With his growing prominence as a spokesman for conservative causes, Ralph spent less and less time at the university. From the mid-1990s onward, his standard teaching load was an easy two courses per year along with a few directed readings. He also spent substantially less time directing graduate theses.”

By contrast, Al Plantinga rightly earns high praise from Sayre for his dedication to directing students. From 1985 to 2010, Plantinga directed or co-directed 20 dissertations. “In terms of theses per year,” writes Sayre, “this level is exceeded only by Yves Simon.” But from 1985 to 2009, McInerny directed or co-directed 24 dissertations, contributing to a career total of 48 dissertations, a Notre Dame record. (Since coming to Notre Dame in 1958, Sayre has directed 12 dissertations, the last in 1991).

Those who worked with Ralph as a dissertation director in the 1990s (as I did) can attest that Ralph was more available than any other professor we knew. Virtually every afternoon, any of us could come to his office without appointment and spend as much time as we needed talking about our work.

“All in all,” claims Sayre, “he probably spent more time working with young Thomists from outside the University than with students enrolled in ND’s own Ph.D. program. A case in point was his work with the Thomistic Institute, financed by the Saint Gerard Foundation and the Strake Foundation, which convened each summer under his directorship for well over a decade. Participants spend a week together in campus housing, attending daily Mass along with morning and evening prayers, and spent most of their time discussing St. Thomas and the life of the Church.”

Far from being neglected, graduate students and recent grads from ND were at the center of these summer meetings. We spent even more time with Ralph during these weeks than we normally did. Sayre praises McMullin for organizing conferences that were “a great place for young philosophers to meet leading scholars in their discipline.” The Thomistic Institute served the same purpose. If it was an accomplishment of service for McMullin to bring “young faculty into fruitful contact with senior members of their profession,” how can it be a dereliction of duty for McInerny to have done the same thing?

Sayer’s book includes many charming anecdotes. Years ago, early on one Saturday morning, Ralph, Hal Moore, and David Solomon arrived at Sayre’s half constructed house. These philosophy professors offered their manual labor to bring the structure closer to completion: “Ralph McInerny spent the day chipping mortar off old bricks.” I wish that Sayre had extended a similar charity in his portrayal of McInerny rather than throwing bricks at an old friend.