George Orwell said that there are some ideas so absurd that only an intellectual could believe them? And he could provide whole busloads of names from the English-speaking world.

There may also have had in mind a Frenchmen or two. Jean-Paul Sartre, for instance, who could be counted on to believe the most absurd ideas, such as “Hell is other people” – from No Exit, his widely acclaimed 1944 play.

But Hell isn’t other people. Hell is being alone, absolutely and forever – when the soul says to God, “I don’t want to love. I don’t want to be loved. I just want to be left alone.” And God, who paid us “the terrifying compliment,” as C.S. Lewis put it, of taking our freedom seriously, will not destroy it, not even to spare us from taking ourselves straight to Hell.

When I was growing up, it was widely supposed that we were in an Age of Anxiety (a phrase of W.H. Auden’s), which meant that we were expected to feel continuously threatened by The Bomb. But at some point, there appeared another age, even worse, the Age of Absurdity, in which the question became: what if The Bomb doesn’t explode, and the world still remains wretched?

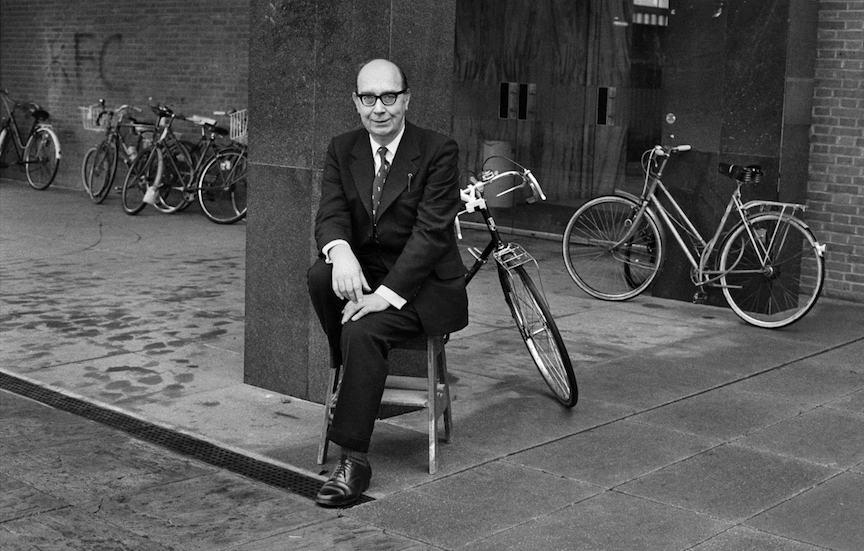

Not since T.S. Eliot, who gave us “fear in a handful of dust,” has anyone expressed that particular preoccupation, the sense of life bereft of sense and galloping towards the grave, better than the popular British poet Philip Larkin, who died in 1985, aged 63, having anatomized absurdity in pitiless detail.

But with a certain wit, as in the last lines of “This Be the Verse,” where he distils a vintage despair so pure that to drink it means no human relation could possibly survive:

Man hands on misery to man,

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can

And don’t have any kids yourself.

Larkin certainly took his own advice. He never married. Though he had a lively interest in women, it never evolved into anything approaching a lasting love. “How will I be able to write,” he complained to the woman he was engaged to in his twenties, the first of many entangling affairs, “when I have to be thinking of you?”

Best to keep your distance lest an attachment spring up that would complicate things. As he put it into a poem whose very title (“Love”) reveals the sad irony surrounding his life: How can anyone possibly be satisfied,

Putting someone else first

So that you come off worst?

My life is for me.

As well ignore gravity.

But what if the true story of love involves a very different sort of gravity, one that finds its fulfillment precisely in the act of falling over and over in love with the same person? What if, in other words, you were really to live the logic of love?

Poor Philip Larkin. That was a paradox he was unable to parse. “(M)y trouble,” he once told a friend, “is I never like what I’ve got” – the predicament of every self-centered person, a subject on which Larkin was an expert.

“He married a woman to stop her getting away,” he writes in “Self’s the Man,” to cite a characteristic example, “Now she’s there all day.” Or this from a notebook: “Not love you? Dear, I’d pay ten quid for you: / Five down, and five when I got rid of you.”

“Deprivation,” as he used to say, “is for me what daffodils were to Wordsworth.” “Doubtless he was sad,” declared his friend A.N. Wilson, recalling the one poet of our time who “found the perfect voice for expressing our worst fears.”

Especially those that come with death, a horror and calamity from which there was no escape. No exit indeed. For Larkin, death brought only the certainty of extinction. “It was a fact,” reports Wilson, “which filled him with terror and gloom.”

Not even the consolations of religion could avert the nothingness that awaits us all. “That vast moth-eaten musical brocade,” he called it. “Created to pretend we never die.”

Nowhere does death appear more fearfully certain than in “Aubade,” a poem written near the end of his life. The title suggests it ought to be a song about dawn, full of hope and promise. But it isn’t. A man awakens at four in the morning, and looking about the room sees “what’s really always there: / Unresting death, a whole day nearer now, / Making all thought impossible but how / And where and when I shall myself die.” Nothing can deflect that fear, not even courage. “Being brave,” he insists, “Let’s no one off the grave.”

According to A.N. Wilson, it was the one poem “written in English in my lifetime of unquestionable greatness.” And yet, you might argue that another of Larkin’s poems, “Church Going,” shows that his whole generation could not rest in his bleak vision, that intimations of something remained beyond that time and place and mentality.

“Church Going” recounts the abandonment of the churches in Britain, but ends:

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognized, and robed as destinies.

And that much never can be obsolete,

Since someone will forever be surprising

A hunger in himself to be more serious,

And gravitating with it to this ground,

Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in,

If only that so many dead lie round.

Who can disagree? Which leaves the necessity of commending his soul and similar souls to God, to the One who also feared death, then vanquished it upon the Cross.