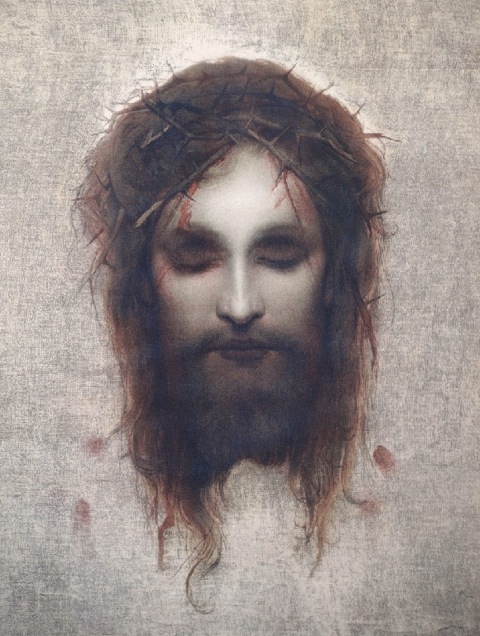

There is an old image of Jesus, solely of his face. His features are pale, worn, and haunting, with dark, penetrating eyes that sear into a man’s soul. Though once quite popular in Catholic homes, it is now rarely to be found. The painting is Gab Max’s “Jesus Christus,” completed in 1874. It is a shame that contemporary Christian culture has developed a bit of revulsion to such paintings, which reflects what I would argue is a tendency among Christians in our day to want only a happy, joy-filled Jesus, rather than the man who died a terribly brutal death upon the cross.

I have a deep familiarity with this particular rendition of our Lord. It was a print that hung at the bottom of the stairs, between the office and the guest room, at my Catholic grandparents home in the mountains of western Virginia. I first encountered it as an elementary schooler. As a young boy (whose parents had traded the Catholicism of their own upbringing for a vibrant, less severe evangelicalism) the painting terrified me. I had come to expect and envision a loving, tender Jesus, not one whose hollowed eyes seemed to follow me through the darkness of the house on my way to the bedroom. I would practically sprint past it, afraid to encounter such a disturbing image of Christ, and maybe even a little afraid He would come and get me!

It now, ironically enough, sits in my garage, one of many items bequeathed to me by my grandparents, something my wife and I had forgotten about while abroad in Asia the last three years. When my wife saw it, she was, like my boyhood self, a bit unnerved. She pressed me to get rid of it. Yet I think the message that visage proclaims is one all Christians need to hear and absorb into the recesses of their devotional life.

Christian – and frequently even Catholic – culture has become intensely focused on the Savior as the loving, welcoming, joyful Jesus who bid the little children come to him, who healed the sick, and loved the sinner. These are all true, important aspects of Christ and His ministry. Yet it is incomplete, and if we narrow our focus to these archetypes, our own faith will accordingly weaken.

We must remember, even apart from the Lenten season, the role of Jesus as the suffering servant of Isaiah 53:

He was despised and rejected by men;

a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief;

and as one from whom men hide their faces

he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

Surely he has borne our griefs

and carried our sorrows;

yet we esteemed him stricken,

smitten by God, and afflicted.

But he was wounded for our transgressions,

he was bruised for our iniquities . . .

As Mel Gibson’s “Passion of the Christ” so brutally portrayed, before the resurrection that brought us new life, Jesus’ flesh was ripped apart by nails that bound Him to a cross, where He bled for hours, mocked and scorned by those He came to save. The words he spoke on Golgotha do not evince a man full of light-hearted joy, momentarily suffering before entering into heavenly joy. Rather they are those of someone experiencing the deepest pangs of grief: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” It is the eyes of a man speaking those words that stare out from Gab Max’s portrait.

In our day, we prize those who are light-hearted, ever-able able to dissipate an awkward moment with a joke. We evade awkwardness like the plague, especially sorrow expressed in public. We call people who are too serious “killjoys.” Moreover, just about every Christian religious group – with the exception of the Westboro Baptist loonies – wants to be viewed as accepting, tolerant, and welcoming. Churches constantly re-brand themselves as non-judgmental and open to all visitors. Bring your coffee into church, wear shorts or flip-flops if you like! One wonders why we continue to emphasize non-judgmentalism so loudly, when nobody is much interested in judging anybody. Even some Catholic leaders succumb to this mentality, bending over backwards to avoid offending people, even if those individuals are public, unrepentant sinners.

This is why we need the Jesus of Gab Max. We need images of our Lord that aren’t warm and fuzzy, the kind of feel-good art provided by such Christian painters as Thomas Kinkade. We need representations of Christ that make us uncomfortable, that haunt our memories, because the price He paid on the cross for our sins is an uncomfortable reality that should haunt us. Every time we sin, every time we return to the confessional, we are in need of a reminder that Jesus, as much as He loves us, as much as He yearns for our fellowship and communion, also suffered dearly to purchase that communion. Anything less trivializes sin. Such truths may also help in moments of temptation.

Many days, I want the loving, all-embracing Jesus who accepts me in spite of all my faults. Sometimes, when our consciences are being pounded like an old punching bag by Satan, that’s what our souls most need. But other times, perhaps many times in our current day, where our culture worships at the altar of happiness, tolerance, and non-judgmentalism, we need a Jesus whose wounds, whose very face, shakes our souls to their depths. Such images are arresting. Indeed, they are terribly uncomfortable.

Then again, the same can be said of the Christian life: “Whoever does not bear his own cross and come after me, cannot be my disciple.” (Luke 14:27)