An article in a military journal recently reported that the U.S. Army concedes that it cannot determine the attributes of good character. The author of writes: “In general, good character is determined by what is required for humans to live well, which can be understood as realizing potential.” He then goes on to say that in a diverse force of about a million soldiers and civilians there are many competing ideas about human purposes.

He suggests that one approach to this moral bewilderment is to concentrate on practical attributes of a good soldier: particularly honor, competence, and commitment. A footnote cites Alasdair MacIntyre’s 1981 book After Virtue, as if he were accepting of our current chaos.

No mention is made, however, of MacIntyre’s championing in the same book of the Aristotelian thesis about the unity of the virtues, nor of his repudiation of relativism, nor of his conversion to Catholicism and to the Augustinian-Thomist convictions that underpin much of his subsequent distinguished work.

In Catholicism, there are three theological or supernatural virtues: faith, hope, and love (1 Cor 13:13) and four natural or cardinal virtues: wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance. (Wisdom 8:7) “Life,” we read there, “can offer us nothing more valuable than these.” From these primordial virtues spring corollary virtues, enabling us to discern and to do that which is Good, True, Beautiful.

Given the secular and pluralist environment of the military services, those concerned with inculcating virtue are doing the best they can. An article in a military journal is not a paper to be read at an academic conference on virtue ethics. Moreover, one also understands that it is not, and cannot be, the task of the Army to train recruits in a given faith tradition or its moral fruits.

The idea that “there are many competing conceptions of what the purpose of a human being is” reminds us, though, of the famously muddled comment of Justice Kennedy in Casey: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

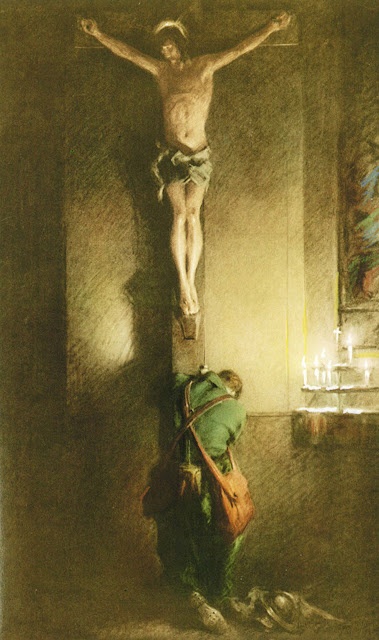

By contrast, St. Gregory of Nyssa taught: “The goal of a virtuous life is to become like God.” (CCC 1803) We become like God by knowing, loving, and serving Him; we accomplish those ends through unswerving fidelity to the settled teaching of Christ’s Bride, (CCC #2037)

Bishop Fulton J. Sheen once put it, succinctly: “If you don’t behave as you believe, you will end by believing as you behave.”

This does not mean Catholics should shun military or other public service. It does mean – emphatically – that when loyalty to God clashes with loyalty to Caesar, one must choose obedience to God. (Acts 5:29) The soul is never the property of the state.

The heart of the military legal system is that all actions and orders must be reviewable by experienced peers and justiciable, if necessary, by courts-martial. In other words, every military decision is, in that respect, public. Appeal to the need for secrecy must be entertained only rarely and only when there is clearly compelling military necessity (as in the case of an immediate military strike).

Beyond “publicity,” however, there is another, and higher, criterion in militarily doing good and avoiding evil: it is the soldier’s conscience, formed in and by at least rudimentary recognition of the principles of the natural moral law.

During the My Lai trial, the judge asked the jury to determine if the murderous actions of U.S. troops at My Lai in Vietnam would have been committed by men “of ordinary sense and understanding.” All soldiers are responsible for disobeying illegal orders, including, most certainly, the order to open fire, intentionally and even exclusively, on unarmed and unresisting men, women, children, and babies.

Good men would refuse to obey such a depraved order.

Now, where does such knowledge come from? “Honor” is a relative concept, for it depends upon judgment of a given group; “competence” can mean the functional ability to carry out even immoral orders; similarly, “commitment” may be to nefarious purpose.

All groups have “values.” Virtue, though, “is an habitual and firm disposition to do the good.”(CCC #1803). Good men strive to be virtuous – to do well what they know and to know well what they do.

As it is not the task of the state to inculcate Catholicism, neither can military training be thought of as the teacher of virtue. It is, though, the task of the Church – and of us Catholics – to teach and model the virtuous life (CCC 2044), so that those embarking upon military or public service will have thereby sharpened the inchoate sense of right and wrong which is written on the human heart.

Virtue education inoculates against both mental and moral confusion.

The wisdom to do good and avoid evil is, or should be, the wellspring of Catholic education at every stage, from grade school to graduate school. Then, when Catholic school alumni approach their adult jobs, they will bring with them, by the grace of God, consciences virtuously formed, enabling them “to discern, in every circumstance, our true good and to choose the right means for achieving it,” (CCC #1835)

Catholics should, in fact, be trustworthy soldiers (CCC #2310), as Catholics ought to be sterling citizens because their virtuous fidelity to what is supernaturally Right ought to provide them the principled light to discern and do what is legally right but refuse to do what is morally malignant.

This is not “values clarification,” but the cultivation of virtue, by the glow of which faithful Catholic soldiers and public servants do their duties, “glorifying the Lord by their life.”