My friends and family sometimes berate me (gently) for my longstanding habit – since my teen years – of reading the New York Review of Books. And, true, many other things might lay greater claim to your attention. Though it’s America’s premiere book review, NYRB is very ingrown. (It could be called the New York Review of Each Other’s Books.) Mostly Jewish, secular, New York liberal – and almost always pushing a point of view you can predict without having to read. There are days when I wonder myself if NYRB and most of the American intellectual class are merely fretting and fiddling with frivolous secular obsessions while our whole civilization burns.

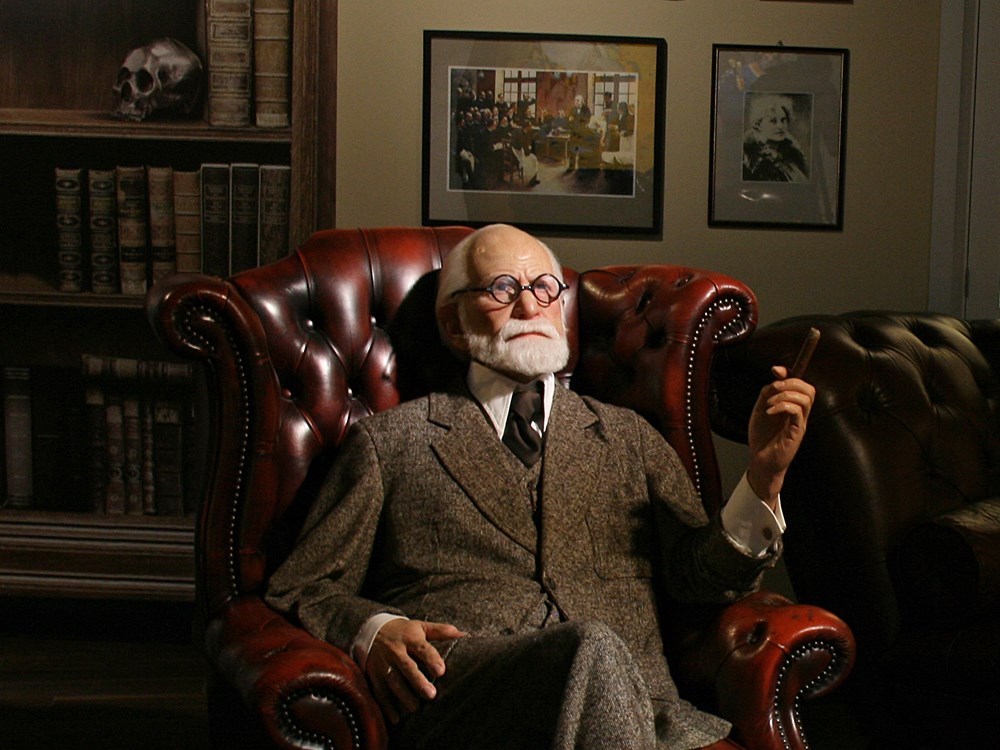

But in addition to reviews of books you might not otherwise hear about, NYRB is a convenient way to take the temperature of the culture. And sometimes there’s a surprise, as in a recent article by Frederick Crews about the scholarly demolition of Sigmund Freud. No one talks much about Freud these days. But he’s a prime example of a much bigger phenomenon in modern culture: the way that some dead intellectual, as John Maynard Keynes once famously said, continues to enslave even practical men and women of the world, despite the fact that his theories, once thought the last word in rationality and social revolution, have proven false.

Freud famously wrote about God as the psychological projection of a great big Father in his book The Future of an Illusion, and he’s responsible for no small part of modern secularism – and the sexual revolution. But as is often the case with people who are themselves psychologically disturbed, it was Freud who was doing the projecting – projecting a whole raft of notions he claimed were scientific but have increasingly been shown to be peculiar to a certain sector of Vienna in his time and, even more telling, to his own peculiar psyche.

Several biographers, even some who want to continue defending Freudianism, have noted the inconsistencies and outright contradictions in Freud’s work, beginning with his lack of careful observation or real insight into the people and world around him. Though he worked hard to make his daughter Anna his intellectual as well as physical heir, for example, he never noticed that she was lesbian.

But that’s just for starters. Crews says of the most recent biographer that she documents how, “Freud was slow to recognize the Nazi menace to Jews in general and psychoanalysis in particular. She tells how the ailing patriarch, obsessed with his privately chosen enemy, the Roman Catholic Church, blinded himself to the greater threat and then, when it materialized, failed to take a principled stand against it – even acquiescing in the purging of Jews from the German branch of his movement, which was surviving in name only.”

But what of the theory – Oedipus Complex, id-ego-superego, sublimated sexuality, the Freudian “slip” (revealing secrets) – that college-educated people have been taught and often swallowed since the early 20th century? (A large number of NYRB’s writers and readers give the impression of being personally invested, as shrinks or patients, in psychoanalysis.) Far from being the result of careful empirical observation of facts that were then assembled into an explanatory scientific framework, Freud basically made it all up: “[Freud’s theory] is best understood not as an accurate picture of the mind but as a serving of warmed-over Romanticism, spiced with a misleading dash of determinism.” The Oedipus “template,” for example, “was imposed on Freud’s patients rather than deduced from their cases.”

It’s no wonder that, in clinical settings, lengthy and often ineffective psychoanalytical talk therapy has largely given way to treating people with drugs. Or even worse, to the sometimes dehumanizing reductionism of neuroscience. Ironically, since Freud, we’ve embraced so shallow a view of ourselves that, even if it was largely a fantasy, Freud’s approach looks almost humanistic by comparison. At least he knew who Oedipus was, and enough Latin to think in terms of id-ego-superego. How many “scientists” would know even that much now?

This whole history reveals how stubborn cultural myths are – even after they have been factually discredited. You could easily produce a theoretical demolition of Karl Marx, too – to say nothing of the evidence of horrors that were visited during the twentieth century on the populations in every nation where his theories were actually tried. But somewhere in the background, for us all, Freudian and Marxist vestiges continue to warp our view of ourselves and the world.

In a scientific culture like ours, we rightly value the way we’ve developed agriculture, medical science, the Internet. And it’s only natural that we look to the scientific paradigm to help us with understanding ourselves and our society. But since scientific verification doesn’t seem to count for much against popular theories, the Gulag and the endless, fruitless hours on the couch by Manhattanites don’t seem to have much reduced the influence of Marxism or Freudianism.

The common element of the two ideologies – and the thing that arguably makes them both so attractive to a certain kind of person – is that they both take the view that you are the victim of “false consciousness” (Marx) or dark subconscious forces (Freud). In other words, your views and actions are false and driven by disreputable motives that you hide from others – and even from yourself. Meanwhile, they (Freudians and Marxists) have the real truth about you and the world. In our day, they now make common cause in what’s sometimes called “cultural Marxism,” which has become so much a part of our social assumptions, that few can detect or resist it.

Any Christian, merely on the basis of self-examination, should readily admit how often we conceal from ourselves our greed, lust, selfishness – all the deadly sins. The difference is that we believe that the remedy lies in the proven paths of repentance, conversion, and grace. The old Marxist/Freudian approach has shown its bankruptcy, not only in theory, but in all its now notorious works and pomps.