It has become a kind of drumbeat in debates concerning moral issues to hear that “it’s the 21st century, get over it!” Or: “it’s 2017, not the Middle Ages!” Those who assert such things seem to think that they have made a point that cannot be rebutted; a veritable killer blow to an opponent’s position. This attitude has also seeped into our political discourse. Politicians seem to greatly enjoy castigating the Church, demanding it “keep up with the modern world” on a variety of moral issues.

As a so-called “millennial,” however, I look around me and find this line of thought to be absurd. There is no reason at all why living in the year 2017 should automatically confer upon us moral superiority. The reality is that individual men and women are just as good or evil as they ever were. And we have good evidence to back that up. As G.K. Chesterton once opined, to discover the truthfulness of original sin, all we have to do is step out of our front door. To my eye, this truth hasn’t changed a jot.

History is a crooked path, in part cyclical, rarely and only in short bursts linear. All the easy talk of the progressive “arc of history” has to ignore the most obvious evidence. Great civilizations – including our own – rise and fall. The horror and mass-murder of the twentieth century should have dispelled the naïve belief in constant moral and material progress. Ideologies replaced faith, men forgot God, and both peacefulness and refinement have been in retreat. Yet the drums of the “progressives” beat on, though what we are progressing towards, no one can exactly say.

The disparagement of Western history and culture is at the center of this unexamined modern worldview. It is unnerving to consider that our forebears may not actually have been as ignorant or corrupt as is often claimed. We’d much rather pretend to admire the latest architectural monstrosity than admit that classical structures might reflect admiration for certain public virtues or that the medieval cathedrals are actually effective in raising the soul to heaven. Indeed, it has become passé or downright offensive to speak about the glories of Western civilization. We don’t want Augustine, Dante, Shakespeare, or Bernini anymore; that would be too “Eurocentric” and “elitist.”

The impulse to believe in constant moral and social progress is partly psychological. We like to think that each generation is improving in some way over the last, whatever the evidence in front of us. Along with enhancements in medicine, cell phones, and the internet, we like to think that we’re also becoming better people.

But we’ve seen that, ironically, the common utopian belief in the possibility of creating heaven on earth usually results in mass graves. Thinking of the human being as malleable is intrinsic to this worldview. The Soviets believed they were going to create a “new man;” Western radicals seem to believe it’s possible to teach human beings to be “woke,” and to never offend one another via the slightest “microaggression.” Of course – even allowing that such changes to human nature are even possible – it would take a tremendously repressive apparatus to achieve either. And the dream of such new forms of man and society inevitably must become a new type of religion.

It hasn’t helped that the way in which we perceive morality has undergone a major shift. In a world of NGOs and Twitter, the idea of individual moral improvement – or moral decline –has been almost completely eclipsed and replaced by abstract gestures. Our moral standing is now thought to be assured if we make anti-Trump statements on social media or agitate about boycotting Israel.

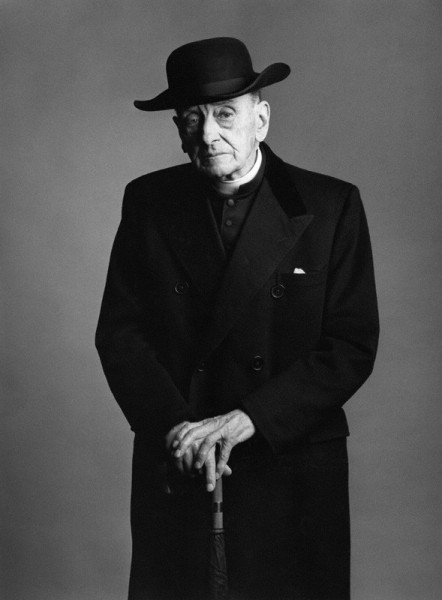

Monsignor Alfred Newman Gilbey, the one-time Catholic chaplain to Cambridge University, understood this change well. He once remarked to the British philosopher Roger Scruton that “we are not led to undo the work of creation or to rectify the Fall. The duty of the Christian is not to leave the world a better place. His duty is to leave this world a better man.” Most of us may still hope that what we do will benefit those whose lives we touch, but the internal struggle is already a heavy enough task.

Gilbey knew that a large part of modern politics is anti-Christian in nature and a danger to the Church. It is not vague reforms of institutions, the family, or society that lead to salvation; it is only through the Blood of Christ. As it says boldly on the façade of the glorious Westminster Cathedral, Domine Jesu rex et redemptor per sanguinem tuum salva nos – “Lord Jesus, King and Redeemer, save us by your blood.”

There can ultimately be only rage and frustration for those who seek to build a utopia in this world. The Christian knows that, in the words of St. Augustine, “you have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” It is only by looking beyond this life that, even in this life, we may find some peace. The post-Enlightenment project of “rationalism” and the disparagement of the Church has not led to moral progress, particularly in my own generation, only to greater anxiety and confusion.