Usually, we consider consistency to be a good thing. Consistency means that we can be relied on to do what we are expected to do. We speak of consistency in a liquid or in batter. We mean that all parts flow smoothly together. In logic, a conclusion follows consistently from its premises without contradiction. All real parts of wholes must be consistent and fit in with the overall object under construction. One piece of a crossword puzzle does not fit. Or the deck of cards has five aces.

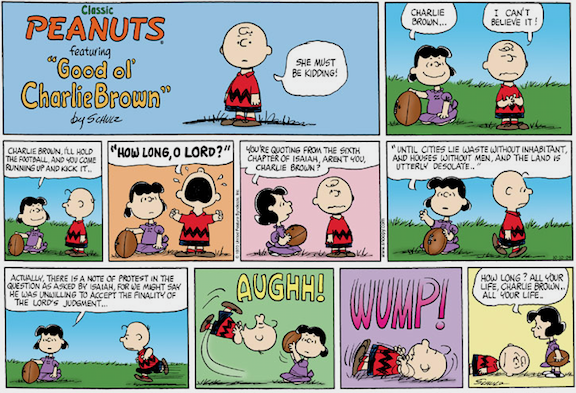

Since this fall is the season of protest, the San Francisco Chronicle the other day reprinted an appropriate classic Peanuts sequence. In the first scene, a befuddled Charlie Brown says to himself: “She must be kidding.” But no, Lucy is there holding the football for him to kick-off. But he is not about to buy this chance for glory after so many times she deceived him. Lucy yet again promises: “Charlie Brown, I’ll hold the football and you come running up and kick it.”

To this dubious assurance, Charlie cries out, “How long, O Lord!” Not fazed in the least, Lucy tells him: “You’re quoting from the sixth chapter of Isaiah, aren’t you, Charlie Brown?” As he walks away with a grim look on his face, she quotes the rest of the passage: “Until cities lie waste without inhabitant and houses without men and the land is utterly desolate.”

In the following scene, Charlie bites. He runs to kick the ball as Lucy holds it. In the meantime, she comments on Scripture: “Actually, there is a note of protest in the question as asked by Isaiah, for we might say that he was unwilling to accept the finality of the Lord’s judgment.” Once the Lord has decided, the issue remains decided.

We keep these words “protest”, “promise”, “finality”, and “judgment” in mind as we see Charlie flip over. Lucy, consistent with her character, at the last moment pulls the ball away from him. He lands on his back with “Aughh! Wump!” Before a prostrate, miserable Charlie, the final words belong to Lucy: “How long? All your life, Charlie Brown. All your life.”

Lucy is consistent. She tormented Charlie with the same scene year after year. We love to watch this struggle between promise of change and the enduring presence of no-change. The scene is a brief summary of Aristotle’s tract on virtue, on good and bad habits. Our character is revealed in our acts.

Charlie is ever trusting, too trusting, naïve, while Lucy is impervious to Charlie’s plight. She cannot resist pulling the ball away even when she assures him that she will change this year. In the last scene, she simply implies: “Look, Charlie, wake up! I am not going to change.”

Thus, consistency, like sincerity, mercy, and compassion, can lead to opposite conclusions. The habits of vice lead us consistently to do the wrong things. We can have sympathy for those who do wrong. We can sincerely embrace evil or praise it.

This ambiguous capacity is in line with the freedom in which we are created and given being. If we have a life or a society filled with people who do vicious things, it is not enough to say that they are consistent. For that is precisely what they are. Virtue means rather to be consistent about the right things. We cannot, in other words, avoid the question of the end to which our consistency points.

A virtuous person remains free to do an evil thing, just as a vicious person can, occasionally, do a good thing. In other words, we can be surprised by either case. We deplore the one and praise the other, provided there is an objective standard by which we measure or estimate the difference between what is good and what is not.

In many ways, however, the most interesting thing about the Charlie Brown sequence was the citing of the passage from Isaiah. God’s decrees will last “until cities lie waste without inhabitants.” When Lucy comes to expand on this unchanging aspect of the divine consistency, she notices that Isaiah may, in fact, be protesting. He did not want to accept “the finality of the Lord’s judgment.” In the last scene, Lucy actually takes this judgment to herself: “All your life, Charlie Brown.”

The “finality” of the Lord’s judgment is consistent with what He is. Mercy, sincerity, compassion, and charity are not tools whereby what is wrong becomes what is right. What measures our actions is not going to change. We can surprise ourselves and others by changing for the better or for the worse. What we cannot do is to surprise the Lord by making what He established as good to be bad, or what is bad to be good. It is on his truth that we are finally and consistently to be judged.