Pope St. John Paul II began his 1998 encyclical Fides et Ratio (“Faith and Reason”) with two words: “Know Yourself.” Knowing yourself is a “minimal norm” for human beings, says the pope. It is a “fundamental question.” which should engage all persons.

Popes and philosophers sometimes say things like this. But how important is it really for regular people living regular lives?

An interesting answer can be found in Walker Percy’s great book, Lost in the Cosmos. In his discussion of “the amnesiac self,” Percy notes that many people seem intrigued by the notion of waking up one day not knowing who they are. Why would this be tempting? Is it because they are so uncomfortable with who they are that they would rather be someone else, almost anyone else? Do you daydream about living an entirely different life as a different person?

So too in the section on “The Self as Nought,” Percy asks why so many people are subject to fads and fashion. Is it because we sense we are a “nought” or “nothing,” and so we buy things like clothes or cars to fill the void and provide the identity we think we lack? After a while, the things we purchase to “change” us become “normal.” We’re left with just ourselves again. So we need to dispose of the old thing and find a new one to create a “new me” different from the “tired-old-me-as-I-am-now.”

Or consider Percy’s “The Promiscuous Self.” Why are people so often tempted by sex with a new person, even an unknown person, even when the relationship with their current mate is rewarding and pleasurable? Surely not all those who cheat are merely seeking something thrilling or dangerous. Is the problem more often that sex with a spouse or long-term girlfriend or boyfriend is like wearing last year’s coat: it has become too much “me,” and now I want to become a “new me,” a “not-me”?

And for that to happen, the old coat, though it is still perfectly good, is now too comfortable for me to feel “new” in. So I cast it aside, though perfectly good, and get a “new me” coat, which, when it becomes associated too thoroughly with “me,” will also have to be cast aside.

If the person you get bored with in a relationship is ultimately yourself, then you may have trouble keeping any relationship going for long. In the end, you’ll be stuck with yourself anyway. Then who will you blame for your dissatisfactions?

Speaking of boredom, why do we get bored? As Percy points out, other animals don’t get bored; they just go to sleep. Do we get bored because other people just aren’t that interesting? Or is there a certain implicit wisdom in the French expression for “I am bored,” je m’ennuie, which literally means, “I bore myself”?

Some people like science and find it fascinating; others don’t. Some can sit through an entire baseball double-header riveted; others are bored out of their minds. Some people actually love watching golf on television. And yet we still might wonder about someone bored by everything.

How does it happen that a human being can be bored by everything in the entire cosmos – not the slightest bit curious about the fact that the whole improbable thing exists at all, with the most improbable thing of all, namely human beings who get bored?

If you are not fascinated by the fact that you exist and exist as you do, doesn’t this mean that, as the French expressions suggests, you are “boring yourself”? Does your existence bore you? Is that everyone else’s fault? Is the world to blame for boring you?

Have you ever wondered what it would be like not to be bored by things and people and instead find each thing fascinating and interesting? If your first reaction to the suggestion is, “Wow, what a nerd I would be!”, this is understandable, but does it tell you that you would rather be bored than be interested in things because of how you fear you might look to others? How many women do you suppose pretend they read and know less than they do in order not to be thought of as an odd “brainiac” by men? You might ask them.

And finally, what about Percy’s “The Envious Self”? Why are so many people attracted to magazines and television shows about the scandals in the lives of celebrities? Are we to think these people hate celebrities and wouldn’t want to be a celebrity themselves? That seems unlikely.

Why is there so much fascination with assassinations, mass murders, and “true crime” shows? Is it because we want to “get to the bottom of the mystery” and see that “justice is done”? If that were true, “true crime” shows would only show stories of “solved” mysteries, not “unsolved mysteries.” But they don’t.

Why is the good news of our friends or neighbors not always “good news” for us? Does their good news make us feel smaller and less significant? Why? If what Percy suggests is true, then we should expect constant conflict, wars, and struggles. But why, then, do we all say we want peace and good things for others if, deep down, part of us really doesn’t? Are we being honest with ourselves? Do we really understand ourselves?

If we don’t really understand ourselves, and our freedom depends upon knowing ourselves, what does this say about our freedom? Either we just don’t want to do the hard work of being free or we are game to work at it, but don’t know where or how to begin. If peace and justice in society depend upon peace and justice in our souls, where must we begin?

Perhaps we need to begin where St. Augustine in his Confessions found he had to begin: in the deepest recesses of his own soul, in that place where God is and we need to find Him.

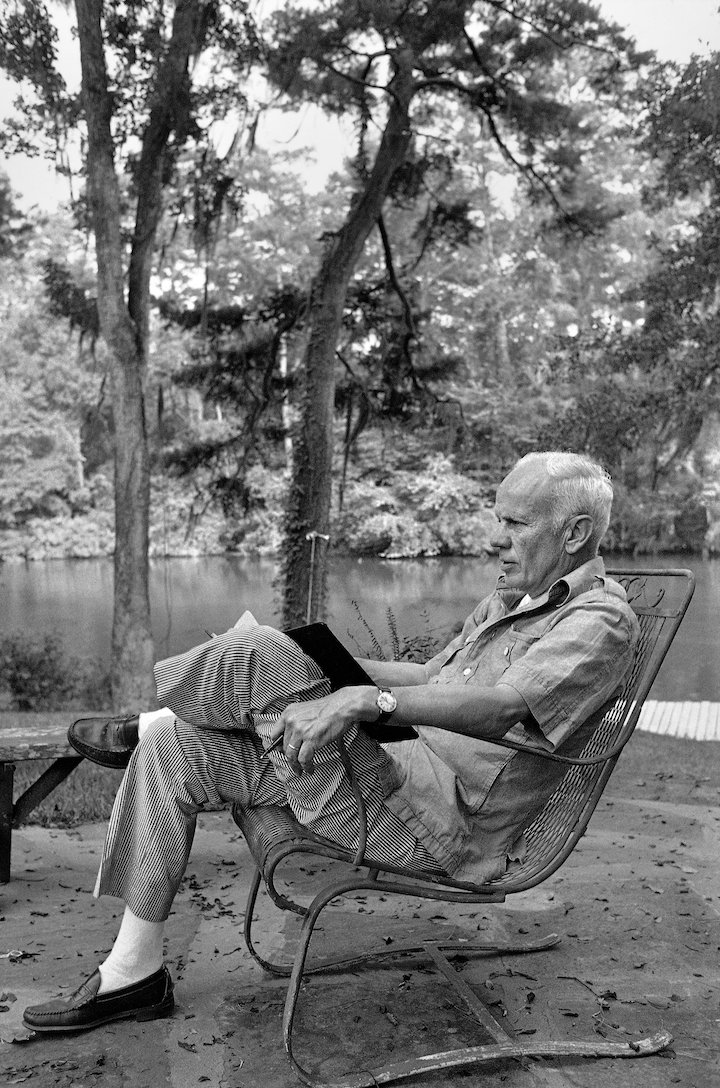

*Image: Walker Percy in his yard, Covington, Louisiana, June 1977 [photo by Jack Thornell/Associated Press]