The December 30, 1996 Ripley’s Believe It or Not contained the following item: “The SkyDome in Toronto uses over ten miles of zippers to fasten its artificial turf.” Off hand, I cannot imagine anyone asking someone else: “By the way, George, how many miles of zippers are in the stadium in Toronto?” But, of course, if I were the manufacturer of zippers or of artificial turf, the information would not be so irrelevant.

The caps on Snapple drinks contain numerous bits of relatively useless information. “Plain Fact #887” tells us: “‘The Valley of Square Trees’ in Panama is the only known place in the world where trees have rectangular trunks.” That information, I confess, does make me wonder: “Why square not round?” Indeed, any instance of useless information can arouse in our minds the same “Why?” curiosity. Some connection between any fact and mind seems evident.

Totally “useless” information does not exist. Today, over half the world’s population carries around a little device. In a moment, it enables them to find the current temperature in Perth, Australia, the winner of the 1934 World Series, or when the Great Wall of China was built.

Table conversation frequently comes down to who can look up what piece of information more quickly. The answer to the tricky question of who was Millard Fillmore’s vice president is right there in our very hands. We carry about with us information that could fill most libraries. Such instruments make us wonder if libraries are obsolete.

And yet, when we have our heads (or hands) full of “facts,” do we really “know” much? Is there a difference between a “fact” and a “truth”? The word “fact” comes from the past participle of the Latin verb facere, to make or do. A “fact” is what is made or done. In this sense, even the world itself is a “fact.” There it is, like it or not. Facts are things we “run up against,” things that cannot be otherwise. Things, being what they are, can also change. That too is a fact. But they change according to some order. Acorns do not produce toads.

Is the primary purpose of education to learn “facts”? Most scientific books will tell us that a human being’s life begins at the moment of conception. It’s a fact, not much sense in denying it unless we choose to deceive ourselves about what is, something we are free to do.

Initially, a fact is something we contemplate. A fact becomes a “truth” only when it is affirmed in a mind to be what its being indicates it is. Truth looks at reality from the point of view of the prior “emptiness” of our minds over against the abundance and variety found in the universe.

We are born with minds. Nothing is in them (tabula rasa) until it is put there, until we affirm or deny some fact to be what it is. Truth does not just mean that something is out there, something that we did not make or put there.

Truth means that what is out there is now also within us. We “become” what it is in a knowing way. We possess it because we know it and affirm what is there as true. Unless we act on it, our knowledge of something does not change the thing known. It merely beholds it as it is. But knowing does change us by making us aware of the existence of what is not ourselves. Knowledge of what is true gives the world back to us.

Interestingly enough in this context, Christ, who is designated as the Word in the Trinity, made two memorable statements about truth: 1) “The truth shall make you free.” 2) “I am the truth.” Our freedom follows truth; it does not constitute it. If Christ is the truth, what follows is a relationship between what He is and what his Father is.

“In the beginning was the Word.” All truth as truth is connected with the “I am the truth.” All freedom as freedom is connected with the truth that makes us free.

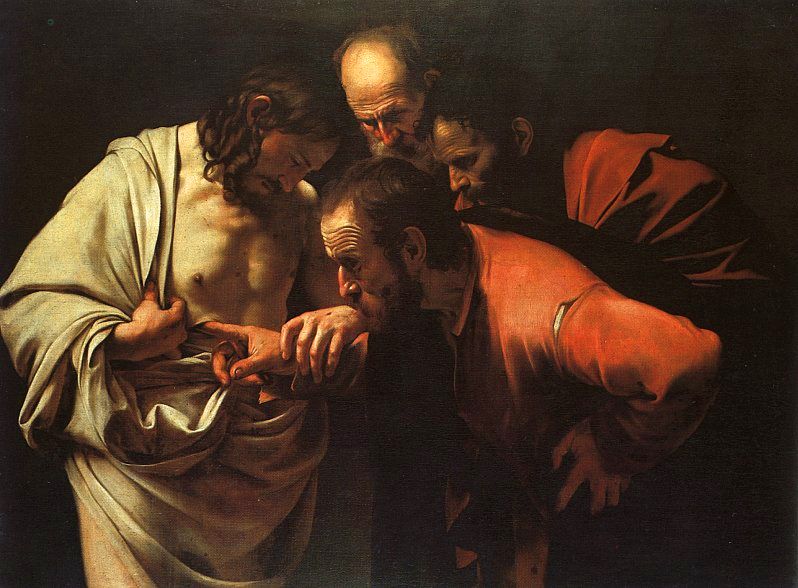

Ripley’s series called itself “Believe It or Not.” Facts can also be known from belief or trust. That Socrates died in 399 B.C. is a fact based on trust in witnesses. We only “believe” facts when we cannot ourselves verify or test them. “Blessed are those, Thomas, who have not seen but who have believed.”

We hear the expression “Seeing is Believing.” Seeing means that we trust the testimony of our senses to tell us the truth of what they behold. If we doubt our senses, we can only speculate about what, if anything, is out there. Many think that the modern world began with this “doubt.” By so doing, it lost contact with what is. “I am the truth” is also a fact.

*Image: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Caravaggio, c. 1601 [Sanssouci Picture Gallery, Potsdam, Germany]