There is a little coffee shop I often work at, which serves wonderful chocolate with its coffee (or decent coffee with its wonderful chocolate, take your pick). It’s what’s known as a “chocolate café” – a marvelous invention of modernity testifying to the endless ingenuity of mankind and to the fact that modernity isn’t all bad. Good espresso and good chocolate, all in one place, and free Wi-Fi to boot. It’s like a little slice of heaven.

And yet even in my little slice of heaven, there are reminders we live in a fallen world. It is not the people eating banana splits or sundaes as big as their heads. Life is too short not to enjoy such treats in moderation. The problems arise from the occasional violations of the basic, unwritten codes of public behavior.

So, for example, in this little coffee-and-chocolate shop, the owners graciously used to leave out a glass full of chocolate-covered espresso beans to which customers could largely help themselves – that is, until a small subset of customers abused the privilege. The people who work at the counter told me that some people would come in and dump half a glass of chocolate into a bag and walk out.

One day a young man took the spoon with which everyone carefully spoons out one or two beans into their hands, plunged it deep into the glass of chocolate, shoved it directly into his mouth, and then plunged it down again into the common glass. Needless to say, the workers had to throw the entire glass away.

It is distressing to see the degree to which more and more people in American society think it is acceptable behavior to treat any public good with contempt. The result is that all of us have fewer and fewer nice things in the public realm, and our public spaces have become less and less congenial to civic life. The particular indignity visited upon the public sphere is often not great – a bit of painted graffiti here, a broken lamp post there, some crushed flowers in a flower bed somewhere else. But the coarsening effect on the public ethos and the cheapening effect on our public life is great.

As I write, there is a gentleman across the way using his computer to scroll through music selections. As one song gets going – loudly – he’ll decide that’s not what he’s looking for and click to another one.

Then there are the people who hold loud conversations on their cell phones in public – sometimes about the most private matters. A student of mine reports she had a roommate who would take calls at 2 a.m. Such people fail to recognize the difference between behavior appropriate for civic spaces and behavior appropriate only for private spaces.

This isn’t about Victorian etiquette of the “My Fair Lady” type. It’s about preserving a public space everyone can enjoy, where everyone feels safe and secure, and which remains both beautiful and welcoming for all. When basic rules of public etiquette break down, one can tell instinctively that what has been lost is an appreciation for the common good.

Indeed, the very notion of the common good has become increasingly inconceivable to our culture of radical individualists for whom the most common interpretation of “the common good” is to insist it is nothing more than the aggregate sum of individual goods. On this view, the more raucous fun I am having, the more I add to the aggregate sum. That’s like saying if I scream or talk during a movie, everyone enjoys it more. But they don’t.

I enjoy public places. I couldn’t imagine writing without human beings around me. But when someone treats our common, public spaces as though no one existed in the world but him or her, everyone else suffers.

You can always go make what you want of your own home: paint graffiti on your own walls, play music as loud as your neighbors will tolerate, talk to your sister about her sex life there. When you exit those doors, you need to think about being courteous to other people, just as they will need to think about being courteous to you.

The philosopher Immanuel Kant created an ethics based on what he called “the categorical imperative,” which went something like this: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” In other words, do something only if you think everyone should do it.

I’ve never found this version of Kant’s categorical imperative all that helpful, but I find myself wishing sometimes that the people would stop and ask themselves of their public behavior: What if everyone did what I’m doing right now? Will the nice environment I am now enjoying continue to exist if I break this lamp or leave graffiti on this wall? Or will this place become just like the other ugly places I came here to escape? What are the inevitable consequences of my actions? How would I like it if someone did this to me or to my home?

Etiquette and courtesy are the oil that lubricates the social engine. A peaceful, harmonious, diverse civic space is a gift that keeps on giving. It allows all of us to feel as though, in some important sense, we are living among friends and fellows, rather than struggling against intractable competitors in a Hobbesian “war of all against all.”

When people treat our common civic spaces with scorn and contempt, they should be gently scolded to teach them what sort of behavior is appropriate. And if they don’t learn, they should be thrown out – gently, but firmly. Those who can’t appreciate a gift shouldn’t have it. And they shouldn’t be allowed to destroy the enjoyment of it by others.

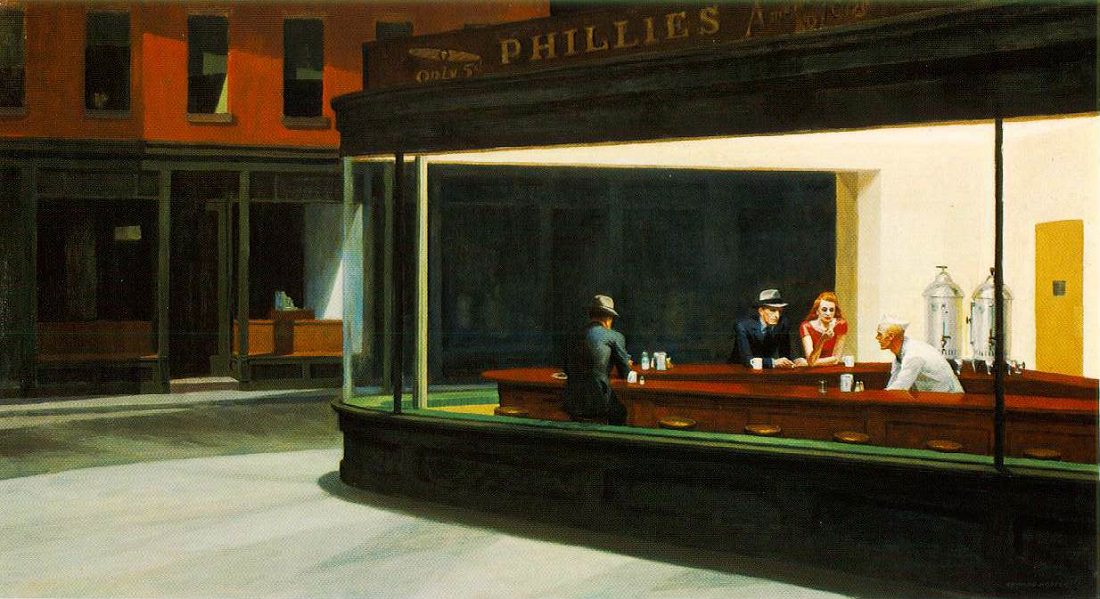

*Image: Nighthawks by Edward Hopper, 1942 [Art Institute of Chicago]