The Autonomous Monastic State of the Holy Mountain is one of the most unusual places in the world. It’s a civilization of monks, by monks, and for monks. This craggy peninsula off the east coast of Macedonia has always been remote and wild. Mt. Athos sits in the middle of it, soaring to 2000 meters. Before and behind are very steep foothills, making travel by land truly arduous. There is no getting to the monasteries from the mainland; all must travel by sea.

Nestled along the shore are the great monasteries, monk towns with numerous chapels, churches, and residence halls, enough to give each monk his own cell and, in the larger establishments, to house the thousands of pilgrims that come each year seeking enlightenment. In their heyday, the larger monasteries had as many as 500 monks, and the big ones like the Great Larva and Pantokratoros created small offshoots, called sketes, a name that comes from the place in Egypt where the Desert Fathers began Christian monasticism in the third century.

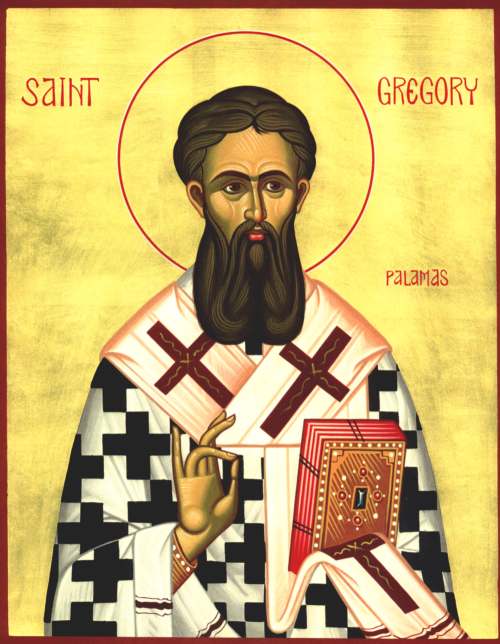

I came to Mt. Athos with a group of Orthodox scholars from Greece and Romania with whom I had been in Veroia (St. Paul’s “Berea”) at a conference on one of the most famous theologians associated with the way of prayer followed by the Athonite monks, St. Gregory Palamas (1296-1356). Palamas spent his formative years in the monastery of Kallipetras, living in caves along the Haliacom River in central Macedonia, not far from Veroia. Kallipetras was never a huge monastery, but Gregory was its abbot for several years.

Today there are only three monks living there, all under 40, one a physician, another a computer scientist, who tell not of Palamas’ skill as an administrator (he later became bishop of Thessaloniki) but of his prayer life. For two days a week, he would leave the monastery and climb into a cave on the cliff. Legend has it that Gregory would spend the entire weekend in the back chamber. There was a small hole that the monks would use to lower in bread and water. The inner chamber, even at noon, is pitch black and silent: virtual total sensory deprivation for 48 hours straight.

Why? Gregory claimed he was practicing the prayer of the heart. He was taking literally the advice coming by way of the psalmist David: “Be still and know that I am God.” (Ps. 46:10) In the stillness, the hesychia in Greek, God speaks to us, he claimed. The darkness did not lead to blindness. In fact, it was “a dazzling darkness.” The light that shown was like the light that the Apostle Peter, James, and John saw on Mt. Tabor when Christ was transfigured.

The light was not just a metaphor for spiritual insight, but an actual participation in the divine nature. God shares his energies with us out of his ecstatic love, through which we are transformed into a Christ-like nature. In Christ, as Athanasius said, God became man, so that we might become God.

Yet this sharing in the divine nature is not pantheism, nor is it a self-exaltation in which we claim, as in the temptation of Eve by Satan “to be as gods.” It is a sharing in common, a koinoneia, a partaking together in love.

God still retains his transcendence. His essence, his divine being, he does not share. That remains unknown and unknowable. The divine darkness takes us beyond our knowing to an illumination, but unknowing cannot ever be totally eclipsed. God is both essence and energy, both known and unknown, both present and transcendent, both action and the fundament of being.

Saints have that experience. That is why they are depicted with haloes, light, Taboric light, which they have seen and which emanates through them. Their experiences are not peculiar to saints.

In Western Christianity, mystical experiences are thought to be limited to special saints. They are not to be sought and they do not save us. The average person would just be confused, so we should not focus much attention on them. In the East, this is different, especially for those like Palamas who insisted that the experience of participating in the divine nature, theosis, was open to all and should be sought by all.

Today hesychasm is practiced in Russia, Romania, and Serbia, but nowhere does it live on more strongly than on the Holy Mountain. All of the Athonite monks are dedicated to it.

The monasteries of Mt. Athos came into existence under the Byzantine Empire. Monks have lived on the peninsula continuously since 800. Tradition states that the Virgin Mary, while traveling with St. John the Evangelist, visited Athos and declared it a holy paradise in which her Son was well pleased.

Out of respect for her, the monks decided 1000 years ago to allow no women on the Holy Mountain. Over the years, there have been assorted women adventurers who have dressed up as men and, like Aliki Diplarakou, a former Miss Europe, snuck in during the 1930s (but didn’t tell her story for twenty years).

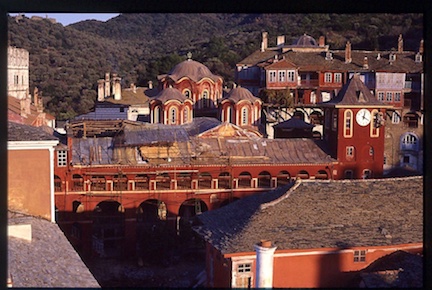

We take the big ferry that sails daily from Ouranoupolis to the port of Dafni in the Athonite State. As we disembark, we run past lines of pilgrims to catch a bus to the capital of Karyes. It’s a tiny place with mostly unpaved roads, a handful of cafes – like Star Wars, but without the bad guys. There’s a municipal building, a couple of churches, and – of course – monasteries. Then another bus, which, like the first, travels slowly over impossibly steep dirt roads. We go through a border crossing, manned by a lay guard employed by the Athonite State, who grabs a teenager from Ukraine with no visa or passport. As the gate finally opens we enter the lands of the Vatopedi Monastery.

In the 1980s, the vast campus of 500,000 square feet of buildings was inhabited by only seven aged monks living in the idiorhythmic style. Then a new group came headed by a Cyprian monk named Joseph who had come to Athos in 1946 and become a disciple of a famous ascetic, Joseph the Hesychast, who died in 1959. From then until 1987, the younger Joseph gathered a group of idealistic disciples. In 1987, they saw an opportunity to invigorate Vatopedi and moved their whole community there. These guys had different ideas from the old monks. The first thing they did was to change the whole monastery to the coenobitic system. This made them less independent, but better able to work together to achieve practical goals.

One of which was the restoration of the physical plant. Phaido Hagianthonious, first came to Vatopedi in 1983 as an architect, employed by the Greek government. A married man who had to leave his family behind on weekdays, he was charged with restoring the decrepit buildings that dated back over 600 years. The old monks did not understand why he was taking so long worrying about the historical character of the structures; they just wanted roofs without holes in them, whether or not they were repaired using authentic materials and techniques.

He had no staff and a small budget. One day early in his time there, he was in the second story of the central church, where he was doing a repair of the roof. As he and his small crew opened the ceiling, down came hundreds of medieval manuscripts, which the monks had hidden there to elude the many pirates and invaders who over the years plundered Vatopedi and the other monasteries, all sitting by the sea, isolated, with only their own walls and defenses.

It was a career-defining moment for him. He knew he would not just be plugging leaks but excavating an important archeological site and restoring priceless treasures. By the time the new group took over a happy coincidence occurred. The European Union started pouring money into historical preservation. UNESCO named Athos a world heritage site, and the new monks were totally with the program. Phaido retired after thirty-two years during which almost 40 million Euros were invested in restoring the vast campus. Today it sparkles.

The campus of churches, residence halls, refectory, and walls sits on a steep seaside hill, surrounded by gardens, where the monks grow much of their own food. From the sea they take fish, from the fields vegetables and fruits. They eat no meat. About half the year, they abstain from fish and oil. Their meals are plain, served on thousand-year-old marble tables, where they eat in silence as a monk reads a spiritual reading from the elevated lectern. They drink water and wine. There’s plenty of the plain but nutritious food. Among the monks, there is a low incidence of cancer and heart disease, and most live well into their 80s.

There are about 120 monks at Vatopedi. There are the grey beards in their 60s and beyond, but relatively few. More numerous are the scores of young men in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. Vigorous and intense, always in the long black robes of the monastery and always with beards. The beards here are as wild as the countryside. Orthodox monasticism is centered in the wilderness.

Its heroes are not statesmen, not scholars at the university of Paris, or leaders in the political centers of Rome or Constantinople, but wild men like Palamas who lived in caves. The whole church reverences these monks in a way that is lacking in the West.

But more about this subject another time.