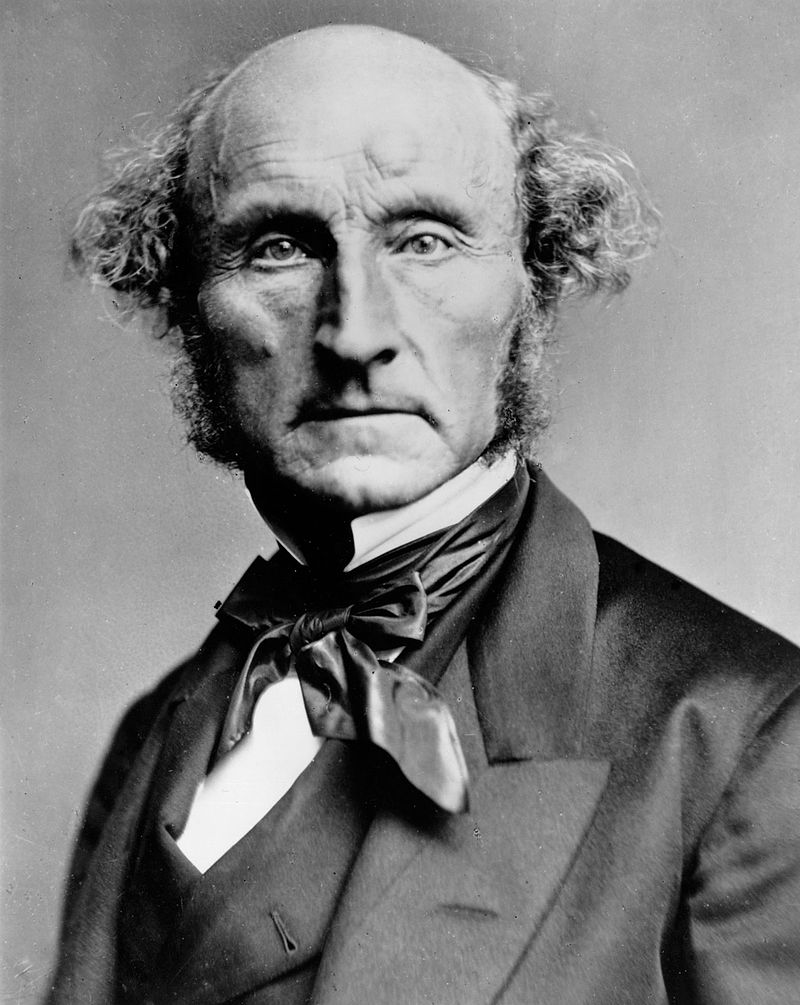

John Stuart Mill’s book On Liberty (1859) is the great foundational document of today’s dominant theory of morality: I mean moral liberalism, the theory that says that, for adults, any conduct is morally permissible provided it does no harm to others. This is Mill’s famous Personal Liberty Principle, a principle that has led Americans – or at all events those very influential Americans who shape public opinion in this country – to endorse sexual freedom, abortion, homosexuality, same-sex marriage, and (soon) euthanasia.

(It is not clear, by the way, that Mill when writing On Liberty meant his principle to be a principle of morality. I suspect he offered it simply as a principle of legal and social toleration. Today, however, is it is generally taken as a principle of morality. Further, if you combine On Liberty with a later of his books, Utilitarianism(1863), I believe a good case can be made that his famous Principle actually is a principle of morality. I note this, just as a matter of philosophical precision, in passing.)

Hence you can do anything you want provided you do no harm to another person. Mill listed three categories of possible harm:

- Bodily harm. Therefore I mustn’t poison you or break your leg.

- Harm to property or money. Thus I mustn’t pick your pocket or shoot your dog or burn down your house.

- Reputational harm. Therefore I mustn’t slander or libel you.

I’ve always thought it odd that Mill didn’t include a fourth kind of harm on his list, emotional harm. For it’s quite clear that some people intentionally inflict emotional abuse on others. This is especially the case in many intimate relationships: parents inflicting emotional abuse on children, children on parents, spouses on one another, boyfriends and girlfriends on one another. Perhaps the most effective way of hurting loved ones is to hurt their feelings.

I’ve always figured there were two reasons Mill left hurt feelings out of his scheme. For one, a certain amount of emotional pain is inseparable from some of the best features of modern life. In a competitive economic system, it is inevitable that many businesses will fail, and the owners of those businesses will experience acute emotional pain when their businesses fail.

Likewise in a democratic political system, those who are defeated in elections will experience acute emotional pain in their defeats. (Being myself an old politician who has been defeated in a number of elections, I can personally testify that losing an election really hurts.)

Shall we do away with capitalist competition, then, because of the hurt feelings of failed business persons, or with democracy because of the hurt feelings of losing politicians? Of course not.

For another, Mill feared that the enemies of social progress would argue against progressive change on the grounds that it hurt their feelings. Conservative men would object to female equality (of which Mill was a great champion) on the grounds that it was an outrage to decent feelings. And American slaveowners would object to emancipation on the same grounds, that the freedom of blacks would be an outrage to normal human feelings.

But perhaps Mill had a premonition of what certain persons in the early 21stcentury would do with the “hurt feelings” issue.

More than a few people (liberal and progressive people) argue today that restrictions should be placed on speech that needlessly causes hurt feelings, for to hurt another person’s feelings is a form of harm. Demands for these restrictions are especially likely to be found on college and university campuses.

Thus mention of the word “rape” by a professor may trigger painful feelings in female students who have either been victims of sexual assault or fear that they might become victims at some future date. Likewise, a campus demonstration against abortion might cause painful feelings to female students (or professors) who have had abortions or who have strong sympathies for women who find it necessary at some point in their lives to resort to abortion.

For such persons, a decent respect for the feelings of women requires that some topics not be mentioned.

Even more obvious – again to some people – is the need for restrictions (and not just on campus) on “hate speech,” that is, speech intended to degrade and diminish women, blacks, Hispanics, undocumented aliens, Muslims, gays, lesbians, transgenders, and others who don’t happen to conform to the American ideal of white male heterosexual Christian.

Not only does this kind of speech hurt the feelings of women, blacks, gays, etc., and hurt these feelings very acutely, but (so goes the narrative) it encourages persons to engage in acts of discrimination toward persons in these groups, who because of this hate speech are often perceived to be less than full human beings.

But (I ask) how am I to tell if, let’s say, a criticism of homosexuality is motivated by hatred as opposed to an intellectually honest conviction that homosexuality is inconsistent with natural law? “Don’t be silly,” I’ll be told. “Criticism of homosexuality is ipso facto hate speech. So is criticism of Islam. And so is criticism of illegal migration. And so is criticism of transgenderism. No need to defend yourself by telling us that your criticism has rational grounds. We know what’s motivating you. Hatred. And in America there should be no room for hatred.”

“But what about free speech?” I ask.

“Is there free speech to shout fire in a crowded theater? Free speech to defame another? Free speech to conspire to rob a bank or commit treason? Why, then, should there be free speech to do severe emotional harm to others?”

For those of us who are Christians, the walls of intolerance are closing in. The proclamation of our beliefs, especially our moral beliefs, causes (it is alleged) pain to others. Therefore these proclamations must cease.

It pleases me to remember that Mill, that famous liberal, would not agree.