Superman, our strongest hero, is also the most circumspect. Clark Kent’s restraint conceals more than any other man’s, but then the art (and depth) of restraint (sprezzatura) is defined by power: the stronger and wiser a man is, the more prudent his manner, the more guarded his speech.

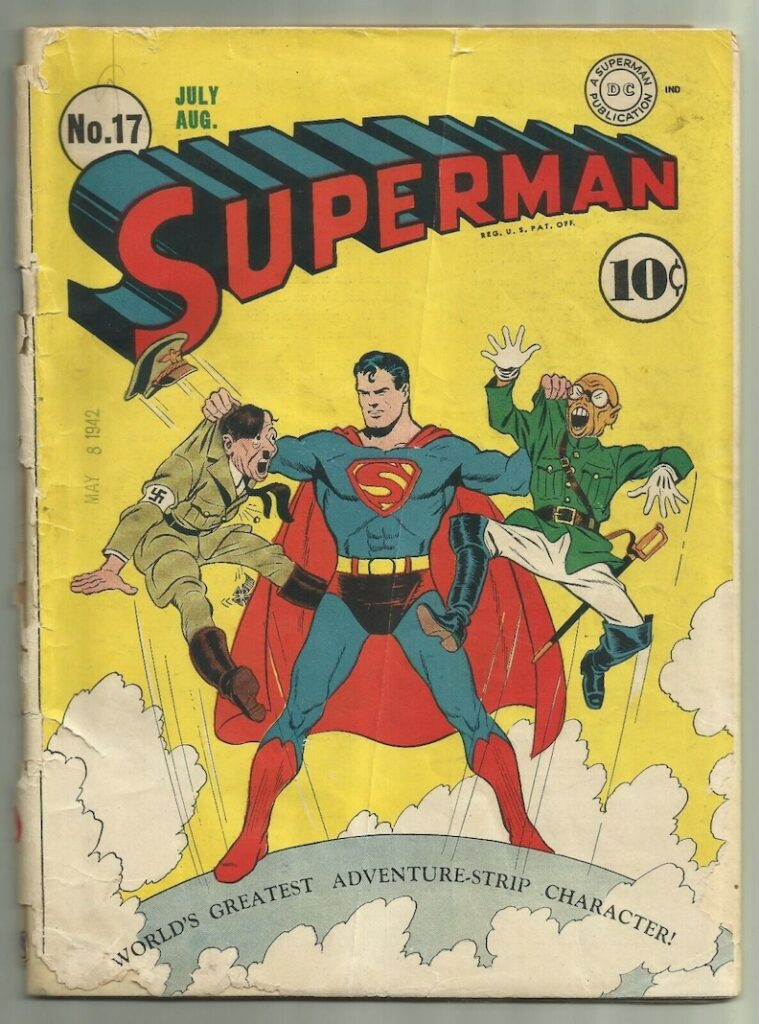

Before his first comic-book appearance in 1938, Superman’s creators, illustrator Joe Schuster and writer Jerry Siegel, had made the Man of Steel a literal Nietzschean Ubermensch, complete with will-to-power villainy. But when DC Comics introduced Superman in Action Comics #1, he was a good guy with a nerdy alter ego, named for two movie stars: Clark Gable and Kent Taylor. The model for the superhero’s look was Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., whose classic arms-akimbo, feet-apart stance became a common motif. Silent-film comedian Harold Lloyd was the inspiration for Clark Kent’s appearance and demeanor.

Although raised by gentle American Protestants, Superman was born on an alien world (Krypton), and his real name is Kal-El, a clearly theophoric construction: the “el”— in either suffix or prefix — meaning “of God” in Hebrew. Kal-El in the Kansas cornfield is rather like Moses in the bulrushes.

Joseph Goebbels thought so. He once railed against Superman’s “Semitism,” probably spurred on by a scathing attack that appeared in the SS newspaper, Das Schwarze Korps, in which Siegel, a Jew, was referred to as “intellectually and physically circumcised.”

Contemporary scholars enjoy bashing Superman almost as much as the Nazis did. Umberto Eco calls him a “conservative” hero, a defender of the status quo and a capitalist lackey, since he only attacks criminals and never — as American liberals would put it —the “root causes” of crime.

But however much an American hero Kent may have become, he remains fundamentally alien — especially with regard to his powers. Thus Bruce Wayne is more exemplary, since his masked identity, Batman, is simply a martial artist with a sense of right and wrong and sufficient learning (and wealth) to fill his basement with myriad crime-fighting gear. But like Kent his heroic identity is hidden.

Some of the most important things about any good man are those he keeps from most people all the time and from those closest to him until the time is right. This applies to his views about politics and religion. It may be tempting when hearing these topics discussed — and recalling Jonathan Swift’s quip that it is “useless to attempt to reason a man out of a thing he was never reasoned into”— to say to the idiot defending the militia movement or touting economic redistribution that he is an ignoramus. But why ought this knucklehead know what’s in your heart?

Bruce Wayne, keeper of secrets, is a Catholic — or so some say, not least Frank Miller, the artist-writer whose 1986 “prestige format” comic, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, helped Batman eclipse Superman in popularity. Like Kent, though, Wayne was the creation of a Jewish artist, Bob Kane (born Robert Kahn), who in 1939 based his character’s appearance and identity on earlier comic heroes such as the Phantom and the Shadow, and on literary and cinematic characters such as Zorro and even Sherlock Holmes. (Writer Bill Finger came up with “Bruce Wayne”: “Bruce” from Robert the Bruce; “Wayne” from Revolutionary War hero “Mad Anthony” Wayne — after rejecting other iconic American surnames such as Adams and Hancock.)

It’s a tribute to the comics industry that these great characters are passed along from one generation of creators to the next and allowed to develop — sometimes in ways the original artist never imagined.

But if Wayne is a lapsed (even tormented) Catholic, he also spent time immersed in some sort of Buddhism — during the years he spent studying the martial arts in Asia — and, all in all, is a man whose passion for justice is religious. It can’t be attenuated — not even by Hollywood.

When my older son, who will soon be Lieutenant Robert B. Miner, was in high school, we went paintballing to celebrate my younger son Jon’s sixteenth birthday. After one of the games, I came upon Bobby back at the “base,” a cinderblock building with a snack bar, leaning back in a chair, feet up on a table, wearing the olive-drab coveralls provided, and with his paintball gun across his chest. He had recently decided to accept an appointment to the United States Military Academy, and I could see already the soldier he’d become. Jon said:

“Bobby, tell Dad about your career plan.”

And Bobby said, holding up a finger to indicate each step:

“West Point. Armor. Special Forces. Ultimate Fighting. Batman.”

Bobby and Jon and young men like them admire Bruce Wayne more than Clark Kent, because Wayne is simply a hero — no alien DNA or accidental superpowers. Such admiration may be no substitute for religious faith, but it is a sharp edge cutting through youthful equivocation to a later, now hidden rectitude.