I had a chance to meet Mother Teresa once. I declined. I heard her speak though – at Cincinnati’s St. Peter in Chains Cathedral, which was filled to capacity one night (if memory serves) in 1974. The priest who’d brought me suggested I attend the meet-and-greet afterwards, but I refused, because it was clear that Mother didn’t want to meet me.

On the back cover of Where There Is Love, There Is God, a new collection of her writings (timed for today’s centenary of her birth), there is a “call-out” quotation:

“What you are doing I cannot do, what I’m doing you cannot do, but together we are doing something beautiful for God . . .”

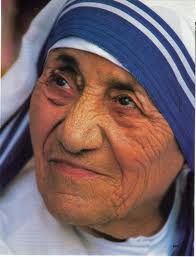

And that’s pretty much exactly what she said in Cincinnati. There were the usual preliminaries in front of the altar (beneath a stunning crucifix by Benvenuto Cellini), beginning, if I recall rightly, with then Archbishop Joseph Bernardin. He had just begun to introduce her when Mother walked over to him, actually tugging on the sleeve (of his seamless garment?) and whispered something to him, which he leaned down to hear. He nodded, and a chair was procured, into which the little woman slumped, staring at the floor, seeming not to listen as the archbishop introduced, I think, the head of Taft Broadcasting, who presented Mother Teresa with a humanitarian award, which she handed back to him after photos were snapped, everybody smiling except her.

Then the microphone was lowered to her height, and she explained that, though grateful, she knew not why they gave an award to her, who they were who gave it, or even where exactly in the world she was. And she said, in that wonderful accent, part Shqip (the language of Albanians) and part Irish-Indian English:

“People often ask me, how can I help you in your work in Calcutta among the poorest of the poor, and I say you have poor here in” – she looked over at the archbishop who whispered the name – and she said, “here in Cincinnati.” I heard Sin-Sin-Naughty, and there was some uneasy twittering (in the old sense) – Poorest of the poor here in southern Ohio? Surely not!

For all the love she radiated, it was obvious to me that Mother Teresa of Calcutta wasn’t interested in meeting Ohioans (or whoever we were) – in trading smiles with yet another receiving line and hearing names and seeing faces she’d never remember. As I watched her gripping the microphone stand and listened to her quavering voice, I felt sad because she seemed then and there the unhappiest of women: very tired, possibly hungry, and definitely a little lost. Dark night of the soul?

By now everybody knows the story of how Agnes Gonxha (that is, “Rosebud”) Bojaxhiu, Sister Teresa, at age 38, a teacher at Calcutta’s Loreto Convent school, suffering from tuberculosis, was on a train heading north to Darjeeling to recuperate when the voice of God called her to a new kind of missionary work. I paraphrase: Pick up the dead and dying, the forgotten and the unforgiven – the outcast and the unloved, and love them until they die. Give them the abundant life they’ve never known. Until they die.

For this work, millions would come to love and respect her and a few to despise and denigrate her, not least Christopher Hitchens, who has described her as “ultra-reactionary and fundamentalist even in orthodox Catholic terms.” She was, he insists, “a fanatic, a fundamentalist, and a fraud.” Having established to his own satisfaction that she was the secularists’ version of Satan, Hitchens then had a hissy fit when John Paul II put Mother Teresa on a fast track to sainthood. Quite the ironic spectacle: an atheist scolding a pope about the procedures of canonization. I’m not among those who expect Mr. Hitchens to suddenly convert, but methinks the gentleman doth protest too much, especially when you consider that the Vatican called upon him to make the case against her beatification. No good deed goes unpunished.

I mention Hitchens because the core of the case he made to the Vatican against Mother Teresa was that (as she told him) she didn’t so much serve the poor as she served Jesus Christ through the poor. As evidence, Hitchens cites as facts: her failure to build hospitals; her failure to advocate economic intervention; her failure to promote abortion.

Fr. Brian Kolodiejchuk, a Missionaries of Charity priest who edited Where There Is Love, There Is God, quotes Mother’s response to a dying Indian man who asked why she did what she did, why she would touch an untouchable such as he:

“I love you,” I said. “I love you, you are Jesus in the distressing disguise. Jesus is sharing His passion with you.” And then he looked up, and he said, “But you, you, too, by doing what you are doing, you, too, are sharing.” I said, “No, I am sharing the joy of loving with you by loving Jesus in you.” And this Hindu gentleman, so full of suffering, what did he say? “Glory be to Jesus Christ.”

This is what Mr. Hitchens cannot accept, because he does not believe in the Son of God. If he did, he’d understand why Mother Teresa – with all her doubts and some mistakes – did what she did, and why she surely is a saint.