I became a Catholic in 1973. I converted to Catholicism about thirty years later.

In those in-between years, faith was an aspect of my identity, but not the locus of my salvation. Like most people, I didn’t think I needed saving. I was a puzzle to myself.

It was good being a Catholic though. It shook up my Methodist family in Ohio – agnostics, yet Protestant to the core. My friends, mostly Protestants, were used to the solar flares of the ongoing identity crisis of my youth, and they could almost admire this particularly bright and colorful eruption, except that as one pal said to me:

“Brad, you do know the pope wears a dress, right?”

No, seriously, why’d you ‘pope’? Boldly I’d reply: Because Catholics are the only Christians who take religion seriously. Oh, I knew plenty of non-Catholics serious to the point of solemn about Christ Jesus, but most attended church maybe once a week, went to shark-like sanctuaries pared down by evolution to the essentials of respectability and fundraising, places to mark rites of passage without need of Communion or genuflection – all stiffly horizontal. There was “outreach” to the poor, although no actual touching of them.

But I’d found my way into this ancient, polyglōttos place of burning candles and statues, of multiple daily reenactments of the Last Supper, and it is as vertical as the upright long post of the crucifix behind the altar and as horizontal as the crosspiece to which the effigy of Christ’s hands are nailed.

You want “outreach”? We’ve got plenty of that. My friends frowned, and I’d add, “But where’s your holiness?” Now they were angry.

“You simply can’t imagine,” I’d tell them, “how much Christ there is in a Catholic church.”

In July I went back to Ohio for a reunion, and, again, my old classmates expressed real interest in my conversion story, because I hadn’t in four decades gone off in another wild direction. Many of these wonderful folks were as solemn as solemn can be – as abstemious as your medieval ascetic, although for different reasons, mostly the old respectability of their parents and grandparents. And, you know, there’s something glorious in it. You want uprightness? They’ve got that.

The few other Catholics in our class are long since lapsed (although fun-loving), and everybody was curious why “as smart guy as I am” is still a Catholic in this day and age, and I thought of Yeats: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.”

Weeks later I got a forwarded email from a fundamentalist I don’t know alleging Catholic abuses that were twenty-first-century versions of the Maria Monk screeds of earlier nativists. But most of my friends were happy that I’m happy; happy too that nearly all of us share belief in “God the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth/And in Jesus Christ his only Son our Lord.”

When I recited this (the Apostles’ Creed) as a kid, I was a bit disconcerted to also confess belief in “the holy catholic church,” until my father directed me to the dictionary and the small-‘c’ definition of the word. A decade or so later I was on the phone with my older brother, and after he asked me what I was up to these days (he in Chicago, I in California) and after I’d replied, springing the news of my conversion, that I was trying to be a good Catholic, he’d asked, unable at first to accept what he’d just heard:

“You mean . . . more universal? How the heck do you do that?”

I chose the title for this column because I imagine something epic – if you can picture a Hollywood poster with giant letters as if carved from stone – because I like to think there’s some Odysseus in me. In all of us. Or, better: Augustine.

But it’s not the journey that matters but the destination: Salvation. I became a Catholic because of liturgy, because of beauty, because of history – all that. But I also “poped” because, in my experience, here was the only Christian literature and the only Christian people to so often and so consistently employ the word Incarnation. I already knew Jesus as the Son who rose from the dead and will return – that’s all Protestant doctrine. But what was news to me was this: “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God.” And for years and years, not a day went by when I didn’t think about that . . . and not a day when I didn’t ignore it too. The world has so often seemed a place marked off by yellow tape. We’re always living in the aftermath of some calamity. Who’s to blame here? Am I? What a puzzle!

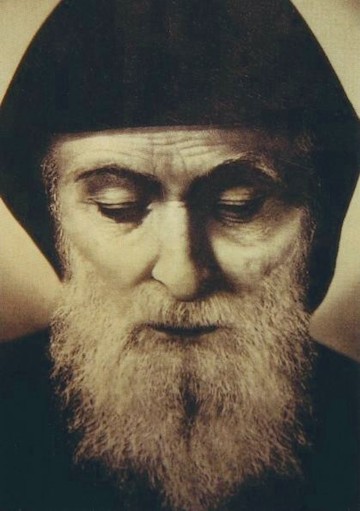

And while I was back in my old hometown I went to Mass every day in the neighborhood Catholic church I never attended as a kid. I loved it immediately (and there are plenty of R.C. churches I dislike with equal passion), and one morning there a priest spoke about a nineteenth-century saint of whom I’d not yet heard, Sharbel Makhlouf, a Lebanese Marionite, who became a hermit and who was devoted to our Lady and to the Eucharist, but who as a child was thought too doltish ever to amount to anything. The priest said:

“His life proves that the human person is a mystery to be loved and not a puzzle to be solved.”

There you go. That’s why I’m a Catholic. And the conversion continues . . . as does the mystery.