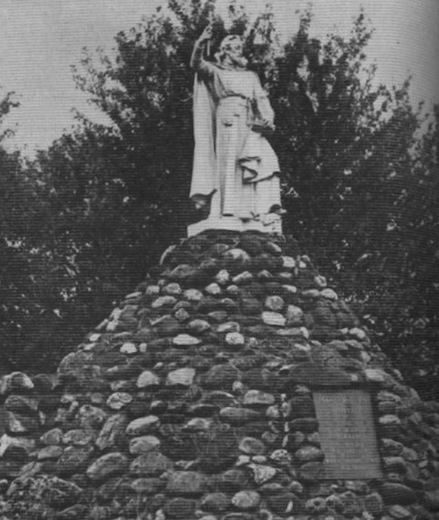

About 200 miles north of New York City in the east-central part of the Empire State, is the village of Auriesville. The Mohawks called the area Ossernenon, and it was a center of seventeenth-century Catholic missionary activity in what would become the United States. Fr. Isaac Jogues was murdered there in 1646.

He was not the first missionary killed in North America; he would not be the last. Seven other French Jesuits were also slain (between 1642 and 1649), known collectively today as the North American Martyrs. (Native-American saint Kateri Tekakwitha was born in Auriesville, ten years after Jogues’ martyrdom.)

Jogues had begun his missionary career in Quebec (New France) in 1636. On a trip south in 1642, he and his companions, French and Native American, were captured by a Mohawk hunting party and taken to Auriesville, where he was tortured. Several of Jogues’ fingers were cut off.

In 1643, he was rescued with the help of Dutch merchants and was taken to New Amsterdam (present-day Manhattan), where the Dutch had been in control since the 1620s. (Incidentally, the first European to see Southern New York was not the English-Dutch – and Protestant – explorer Henry Hudson in 1609 but the Italian-French – and Catholic – Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524.)

Upon arriving in New Amsterdam, Fr. Jogues was met by the Dutch Reformed reverend (or “domine”) Johannes Megapolensis, who described the blackrobe’s condition.

A bronzed, dark bearded face, lined and drawn with suffering, but in the eyes and expression “that peace which the world knows not of.” Of the forefingers and the left thumb of his hands only the jagged red stumps remain. Every finger shows a partially healed wound and from all, the nails are gone.

Megapolensis tenderly guided Jogues along the narrow, muddy streets, with the Jesuit “leaning on his arm, the bent broken figure in rags, partly Indian, partly European, that barely cover him.”

In this town, a village really (soon to be re-christened New York), Jogues would note a remarkable thing about the Catholic population: that in all of New Amsterdam/Manhattan, there were just he, a Portuguese woman, and an Irishman. Thus when Jogues returned to France to recover his health, there were just two Catholics living permanently in what in subsequent decades and centuries would become America’s largest and most Catholic city. (All in all, the residents of the town had, as some historians have written, a “claim to being the motliest assortment of souls in Christendom.” New Amsterdam was ramshackle; less a colony than a temporary outpost.)

After a brief convalescence in France, Jogues returned, and not just to North America but soon to Auriesville/Ossernenon. The Mohawks were impressed by his courage and dubbed him Ondessonk, the indomitable one, which he was until his neck was hacked through with a tomahawk on October 18, 1646.

Writing in the middle of the nineteenth century, Fr. J. R. Bayley (private secretary to New York’s first archbishop, John Joseph Hughes, and himself a future Archbishop of Baltimore) lamented:

Father Jogues’ head was fastened to one of the palisades, and his body thrown into the Mohawk River. Thus perished the first missionary that ever visited our island. His memory was long cherished, even among the Iroquois . . . and, though he has never been formally canonized, yet those who are laboring in the same field under more favorable circumstances, may justly invoke his intercession . . .

All in all, it was not an auspicious beginning for Catholics in New York. Fr. Jogues was canonized by Pope Pius XI in 1930.

Those Dutch rescuers and their governing countrymen in Manhattan were noted for their tolerance. Another Jesuit captive rescued by the Dutch (again from one of the Iroquois tribes), Francesco-Giuseppe Bressani, was likewise treated with respect and honor in New Amsterdam, a year after Jogues had been. Bressani was given a letter of safe passage by Governor Willem Kieft.

Unlike Fr. Jogues, however, Fr. Bressani returned home to Italy, forswore America, and died peacefully in Florence in 1672. During his retirement, Bressani wrote a memoir of his time in America (known as the Breve Relatione) in which he included the text of a letter written to his superior while still in captivity:

I know not whether Your Paternity will recognize the letter of a poor cripple, who formerly, in perfect health, was well known to you. The letter is badly written and quite soiled, because, in addition to other inconveniences, he who writes it has only one whole finger on his right hand; and it is difficult to avoid staining the paper with the blood that flows from his wounds, not yet healed; he uses arquebus [a type of musket] powder for ink, and the earth for a table.

He simply didn’t know, he wrote, that a man could be so hard to kill.

Catholics were deeply indebted to the Dutch, although Dutch tolerance went only so far. It was the rule, even as Jogues and Bressani were affably conducted through New Amsterdam, that in all of New Netherland there was only one religion to be practiced: Calvinism. No Masses could be said in the colony, and the turmoil of the late Reformation period in Holland was reflected in laws that essentially gave second-class status to all religions but the one established. This was especially true under the last Dutch governor (Director General) of New Netherland, Peter Stuyvesant, and that vaunted Dutch tolerance towards Catholics was in some measure due simply to the scarcity of Catholics.

Escorted cordially as those Jesuit missionaries had been, they were always being escorted out. But as we know, that would change.