The quest to ban alcohol in America began during the Revolutionary War. Military men drink. In fact, armies and navies – in the Western world anyway – almost always had enlistment or conscription policies that included daily allotments of rum or whiskey. This was for a simple and sensible reason: potable water was scarce. As Samuel Butler wrote: “When the water of a place is bad it is safest to drink none that has not been filtered through either the berry of a grape, or else a tub of malt. These are the most reliable filters yet invented.”

Then as now, drinking from the clichéd mountain stream is dangerous, even deadly. Fly fishing in the Gallatin River some years ago, I reached down to cup a handful of the limpid, rushing water, and my guide shouted at me: “No! Are you nuts?” The water of rivers and creeks teems with bacteria.

Flowing artesian wells are and were few and far between.

As Americans began migrating west, some form of alcohol was essential for survival in the early years of wilderness living, until the arrival of well digging equipment. Indeed, John Chapman, a.k.a. Johnny Appleseed, made his living by staying a step ahead of settlers: planting apple seeds in designated areas and developing seedling farms; this so pioneers could buy and plant the small trees on their new lands, in fulfillment of the orchard requirement in the land-use rules of the Ordinance of 1787. But apple trees take time (2-5 years usually) to begin to bear fruit (from which cider was made – always “hard”), and the first crop planted and harvested was corn from which whiskey was produced.

And many Americans – often including children – were tipsy (if not, in fact, drunk) much of the time, and thus the calls for temperance and even outright prohibition.

Those calls were mostly unheeded until the end of the nineteenth century, by which time immigrant brewers and native distillers fairly covered the landscape, but at which point also two scientific-industrial developments made prohibition actually practicable: the popularization and availability of sterilization (pasteurization) and of refrigeration. Suddenly, in the scheme of things, you could drink the water.

And, to be sure, alcoholism was rampant, and – in the environment of penny-dreadful journalism, in which tales of fallen men and women, broken families, and horrid crimes were a staple – there was a growing sense that Something Must Be Done! The “Third Wave” of the Temperance Movement began in about 1893 with the founding of the Anti-Saloon League in Oberlin, Ohio, and (to make a long story short) in two decades there was enough momentum in the Movement to propose in Congress and quickly ratify in the states the Eighteenth Amendment (effective on January 17, 1920), which made illegal “the production, transport and sale of (though not the consumption or private possession of) alcohol . . .”

Was there in the Movement the odor of anti-Catholicism, perhaps even of nativism? Oh, yes. The group that more than others made Temperance into Prohibition, the Women’s Christian Temperance union (WCTU), was also racist and eugenicist.

But there was also a Catholic movement for temperance.

The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913 – written before Prohibition – discusses with approbation the Catholic wing of the Temperance Movement, which had its beginnings in the visit to the U.S. of Fr. Theobald Matthew in 1849. Fr. Matthew was known as the “apostle of Irish temperance,” a prophet honored rather more in America than in his own home. He was only the second foreigner to be admitted to the floor of the House of Representatives (the Marquis de Lafayette was the first), and he was feted by President Zachary Taylor. When one reads of Irish immigrants “taking the pledge,” that all began when Fr. Matthew crisscrossed the U.S.: 37,000 miles; twenty-five states (all but five at that point); and half-a-million oaths to swear off booze.

Curiously, however, (perhaps in a nascent spirit of subsidiarity) the resulting Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America was a wholly moral movement, emphasizing personal reform and not wishing to be part of any legal schemes for prohibiting alcohol production:

Our motto is moral suasion. With prohibitory laws, restrictive license systems, and special legislation we have nothing whatever to do. [Emphasis added.] There is blended with our proposed plan of organization the attractive feature of mutual relief. Thus Temperance and Benevolence go hand in hand.

On the other hand, the Union flatly stated it would not oppose laws that shut down some gin mills.

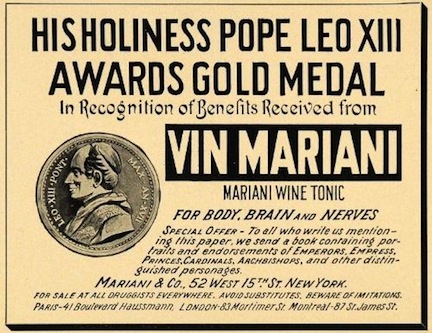

The Union received many words of encouragement over the years from popes (Leo XIII and Pius X among them), but what’s clear from those words of greeting and from the Union’s own pronouncements is that Catholic temperance was aimed at minimizing consumption of spirits and not at banning either beer or wine. As St. Pius X stated it, the enemy was “the abuse of strong drink.” It’s worth noting that both Leo and Pius were happy consumers of Vin Mariani – basically Bordeaux wine infused with coca leaves (10 percent alcohol and 8.5 percent cocaine extract by volume), which promised to “tone and strengthen body and brain.” Leo allowed it to be promoted with his name and image.

Unlike the various Protestant temperance societies, the Union was effectively all-male for its first forty years. In a statement I’ve not seen the like of elsewhere in the old Catholic Encyclopedia, summary tribute is given to Frances E. Willard, a classic nineteenth-century progressive and Methodist president (1879-1888) of the WCTU, as “a gifted woman of high character.” High praise indeed for a blue-blooded, anti-Catholic eugenicist.

But the writers of the Encyclopedia’s “Temperance Movements” article could not have imagined what would result from the good intentions therein reported. And one wonders what the lawless and chaotic Prohibition Era might have been like were it not governed by nationalist Puritanism but had, instead, followed the more enduring principles of subsidiarity and self-control.