Judas is in hell. Despite the contortions of some celebrated theologians such as Hans Urs von Balthasar, it’s quite difficult to find universal salvation in the Scriptures. Even Plato noted that if the extremely wicked were not extremely punished in the next life, the world might seem founded on injustice.

Yet we often hear it said that, since the Catholic Church has never condemned any individual to damnation, we cannot say for certain that any soul now suffers or ever will suffer whatever torments exist in hell.

I’ll come to Judas presently, but let me say that of all the questions folks ask about pain and suffering and sin and damnation, the only one that seems to me to matter is this (which is not the subject of this column): Why are we tainted with original sin? Put another way: Why are we, who never asked to be born, put at jeopardy of damnation by virtue of our coming, involuntarily, into existence?

Very many people I know raise these questions with sincerity, and argue that our minds being so clearly incapable of comprehending either eternal damnation or eternal salvation (what Paul said of heaven in 1 Cor 2:9 may as easily be said of hell: that the true horror has never entered into our minds), it is simply unjust that God would consign anybody to eternal terror.

And the answer to that is Judas.

My older son was stationed at Ft. Knox a couple of years ago and on a Sunday (afterwards, we traveled the “Bourbon Trail”), we went to morning Mass at Our Lady of Gethsemane Trappist Monastery near Bardstown.

Now I had heard that this house had become somewhat non-standard in its embrace of Catholic dogma, but I was hardly prepared for the abbot’s homily about hell. Standing there beneath a tapestry that depicts Lao Tzu, Gandhi, Patrice Lumumba, MLK, and other sages and martyrs for peace, the priest made the claim that hell may well be empty. I can’t recall all those to whom he gave a get-out-of-hell-free card, although Adolf Hitler was mentioned. Did he include Judas among those for whose salvation we may hope? By the abbot’s own logic, he should.

The trouble with this abundance of compassion is Christ’s own very clear assignment of Judas to perdition. John records the Lord’s prophetic prayer at the Last Supper:

And now I will no longer be in the world, but they [the Apostles] are in the world, while I am coming to you. Holy Father, keep them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one just as we are.

When I was with them I protected them in your name that you gave me, and I guarded them, and none of them was lost except the son of destruction, in order that the scripture might be fulfilled. (17:11-12)

The fulfilled scripture Jesus cites is the 41st Psalm: “Even my trusted friend, who ate my bread, has raised his heel against me.” And – almost as if in answer to the questions about original sin, redemption, and damnation – in Mark (14:21, in the same Eucharistic context) Jesus says: “For the Son of Man indeed goes, as it is written of him, but woe to that man by whom the Son of Man is betrayed. It would be better for that man if he had never been born.”

Never been born. Given that we do exist, and given the ecstasy promised to the saints, and given even the joys of this world, how can “never been born” not imply that Judas forfeited paradise? Clearly, he is damned.

Again, it is sometimes argued, given other prophecies made that same night, specifically about Peter, that the Apostles still did not know who Jesus really is. Yes, they believed Him to be the Messiah but believed as most Jews understood their deliverer to be: God’s chosen one, but not God Himself.

But that hardly mitigates Judas’ betrayal; his suicide seals the deal. Both Peter and Judas denied Christ, but Peter repented.

Saint Augustine described humanity as a massa damnata, which phrase needs no translation. We are children after the Fall, haunted by concupiscence – a mystery rooted in our resemblance to God: in our freedom. We know we’re fallen. Experience teaches us so. No socio-political system will ever free us from bondage. We know hell exists because Jesus made its existence perfectly clear in His earthly ministry. We know those who dwell therein are rightly condemned, for our just God would not allow it to be otherwise.

Neither Scripture nor tradition gives us reason to anticipate a second Harrowing of Hell, such as we evoke in the Apostle’s Creed.

On another Holy Thursday, this one in the year 1300, Dante “began” his descent into Inferno. Unable to find the diritta via (straight way), he and his guide, the Limbo-dwelling Virgil, hike down through all nine circles. Short of heaven, the best any unrepentant sinner may hope for is to be with Virgil and the other melancholy residents of Limbo, although such an end is unlikely for a damned Catholic.

And lest one think the Divine Comedy, being neither Scriptural nor Magisterial, cannot educate, consider that Benedict XV devoted an encyclical to it (In Praeclara Summorum, 1921) in which he wrote that the “divine” Dante “depicted the triple life of souls as he imagined it in a such way as to illuminate, with the light of the true doctrine of the faith, the condemnation of the impious, the purgation of the good spirits and the eternal happiness of the blessed before the final judgment.”

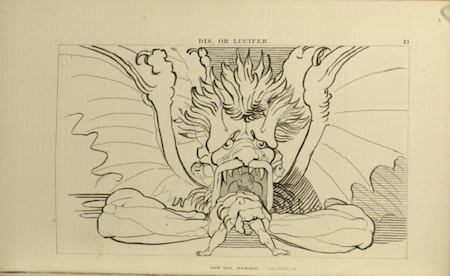

In the Ninth Circle, the very bottom of Inferno, where all is ice, fanned frozen by the furious flapping of Satan’s wings, Dante and Virgil find Judas. The Devil gnaws on Judas’ head and claws at his back. Forever.