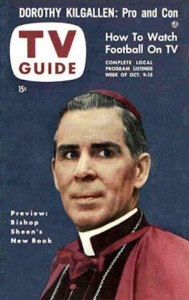

Everyone of a certain age knows of famed Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, who explained Catholic doctrine effectively on national television as no one before or since. Why don’t bishops do that now? Some do it locally, but couldn’t our bishops’ Conference produce even one bishop – there are about 270 – who knows enough about doctrine and can work with good writers, graphic artists, and editors to produce a half hour of high quality Catholic content weekly – and present it with brio?

Fr. Robert Barron’s excellent series Catholicism, for example, gained a wide, if fragmented, audience. A ranking churchman of similar gifts needs to appear, however, for two reasons. First, it takes guts to speak about chastity and morality and community to a national audience, but “all the nations,” even the United States, have to hear this truth. (Matthew 28)

That’s why Christ appointed apostles. The apostolic nature of the Church is on the line. Christ did not tell the apostles to go forth and produce offices with large bureaucracies. There is something essential in personally presenting the truth with conviction, which is why Christ worked that way and not via Vulcan mind melds or skywriting.

Second, only Catholicism can raise the subjects that are missing in our national discourse. That they are missing, despite the fact that the episcopate has existed for so long in America, is a subject for another time. But to be clear: Catholicism is not a ghetto religion. It stands boldly in the market place and takes on all comers. America needs to hear the roar of Catholicism.

But why a bishop? Well, they hold the official teaching office in the Church, yet up to now, except for speaking now and then to congressional committees and the occasional interview with a reporter, the bishops have been invisible in the public square. Why receive the apostolic grace if you’re only going to hide it under a desk?

Their reticence fits the modern stereotype of what a bishop, the figure of Christ, should be in secular society – namely, quiet and invisible. Local culture, however, is not supposed to define a bishop’s activity. Grace already does that. It is the sovereign autonomy of God’s revelation in Sacred Scripture and Church tradition that holds sway – if, of course, you take scripture and tradition seriously.

These two influences – culture and the Church – are not equivalent or interchangeable sources of meaning. A culture that is fiercely solipsistic needs to hear what real human community and what real human being are from the Church – rather than from the culture, even if it be the culture of a major, though declining, economic and military power.

You’d think that maybe the apostolic examples of St. John Paul II or Pope Francis – even when they were a tad busy – would influence the activity and style of bishops generally around the world. And, yes, there are some bishops who make an effort to be in contact with ordinary people, but how many? There are still so many people in the world who need to hear the Gospel.

Benedict XVI, for example, told the German Parliament: “it is evident that for the fundamental issues of law, in which the dignity of man and of humanity is at stake, the majority principle is not enough: everyone in a position of responsibility must personally seek out the criteria to be followed when framing laws. In the third century, the great theologian Origen provided the following explanation for the resistance of Christians to certain legal systems: ‘Suppose that a man were living among the Scythians, whose laws are contrary to the divine law, and was compelled to live among them. . . .such a man for the sake of the true law, though illegal among the Scythians, would rightly form associations with like-minded people contrary to the laws of the Scythians.’” He said this to the German politicians because he knew they need to hear this – to them – uncomfortable truth.

The Catholic Church really does have something urgent to say – even though there do not seem to be many bishops in the United States radiating confidence or excitement about this crucial fact. And the Church does not just raise “issues” that have been overlooked or rejected. It also protects the very structure of thinking itself – look at JPII’s largely unstudied Fides et Ratio.

We hear a lot about encouraging the laity to evangelize. That might gain some credence with the Catholic people if they saw bishops were doing it. Courageous examples in national life would help clergy and laity to see what they ought to be doing and how to do it. Then the effects of God’s initiative expressed through the initiative of the bishops would light the way.

As Leo XIII said more than a century ago about this process, which has repeated itself throughout Christian history: “there at once burst[s] forth a certain creative force which issued in a new order of things and pulsed through all the veins of society, civil and domestic. Hence arose new relations between man and man; new rights and new duties, public and private; henceforth a new direction was given to government, to education, to the arts; and most important of all, man’s thoughts and energies were turned towards religious truth and the pursuit of holiness. Thus was life communicated to man, a life truly heavenly and divine.”