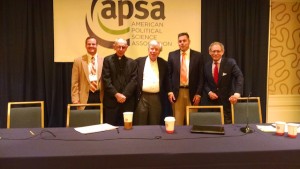

September 2015: The annual meeting of the American Political Science Association but with a special panel now, a cluster of friends and former students to celebrate the teaching of Fr. Schall.

For me this was no ordinary retrospective. Jim Schall became a dear friend when we were colleagues together at Georgetown when I visited there in the early 1980s. And when I finally came into the Church, in April 2010, he was there with me to concelebrate.

As anyone who knows him knows, Fr. Schall has ever been anchored in the world, seeing the world as it is, and that sense of things has always been connected with the world as seen, in a clearheaded way, by political philosophy. One of the persistent threads in Fr. Schall’s writing and teaching is the question, “What is”: What is a table? What is a man? What is a political order, springing distinctively from the nature of that biped who conjugates verbs?

In the opening sections of The Politics, Aristotle says that “the ‘nature’ of things consists in their end or consummation; for what each thing is when its growth is completed we call the nature of that thing, whether it be a man or a horse or a family.” If I hold up here a pen, and we understand the nature of that thing, we understand its telos, the end for which it is made. We know its distinctive work, and we know the difference between one that works well or badly.

If we understand that being, somewhere between the animals and the angels, that being that can give and understand reasons over matters of right and wrong, we know that from his nature only springs the notion of law, and law is the defining mark of the political order. And if we know that nature, we can know the difference between a good man and a bad man, between a good polity and a corrupted one.

But the deepest question for Fr. Schall, and political philosophy, is that question of reason versus revelation. And that is the question that he and I use to ponder in walks through Georgetown. My late professor Leo Strauss thought there was a benign standoff here, for reason could not deny revelation, nor revelation refute reason. But as Fr. Schall noted, both revelation and reason emanated from the same source, and they were accessible only to the same kind of creature.

That creature had the wit to sift between the claims of revelation that were plausible and implausible: “If what is said to be revealed is irrational or contradictory, it cannot be believed, even according to revelation.” If Moses came down from Sinai and said, “The Lord, our God, said not to worry overly much about taking what is not yours, or lying with other men’s wives” – if that were the report, we would have expected to find many Hebrews scratching their heads and asking, “Are you sure you got that one right?”

Lincoln said in his Second Inaugural that both sides in the Civil War “read the same Bible and pray to the same God,” and yet he was sure that “the prayers of both could not be answered.” Whatever the perplexities of the case, Lincoln was sure that God would not at the same time reject slavery in principle – and yet accept it.

As the argument unfolds, Schall says that “we will not understand revelation if we do not understand political philosophy, if we do not understand ourselves.” For Schall, revelation becomes open to us, on the most important questions, when it is opened by people who “study politicks,” as Samuel Johnson had it. Might it be because politics raises moral questions, of right and wrong?

Revelation helps complete our understanding here, as John Paul II would say, by making us aware of “the reality of sin [and] the problem of evil.” But as Schall says, political philosophy points outside itself, and “leads to answers that are not specifically political.”

Such as what? Perhaps to the ground of consolation, when innocent, good people suffer, and when evil succeeds. Or when we raise the question, perhaps, of what the meaning of it all finally is. John Paul II said that a “specific contribution” of revelation has been “the notion of the person as a spiritual being.” And that person may become aware then that this place is not his only home.

Schall says that “reason and revelation both concern themselves with the location of the best city.” For Plato, the best city, the best political order, was spun out in the world of speech. It is not a place we expect to inhabit. But Plato had Socrates say at the end of the Republic that, whether this City exists anywhere or not, it is the only city in which the thoughtful man would wish to take part.

Even so, as Schall says, revelation alerts us to the possibility that our true home will really be elsewhere. As Schall puts it in The Modern Age, “Ironically, it turns out that we will not understand the world if it is only the world we seek to understand. [And] we often suspect, at our highest moments, that in being in this world, we are not made only for it, dear as it can seem to be.”