I serve on the board of directors of Aid to the Church in Need USA. TCT contributor George Marlin is the chairman of the board. ACNUSA is one of many national offices of the international organization that is a pontifical foundation dedicated to helping suffering and persecuted faithful around the world.

Over the last several years, many of our efforts have been focused on the Middle East. Mr. Marlin recently published a book about the situation in these communities, the most ancient of all Christian settlements. (Remember that Saul became Paul on the way to persecute the Christians already living in Damascus.)

But Catholics and other Christians are also at risk elsewhere in the world (one might even say everywhere, in one way or another), and ACNUSA’s outreach goes to more than 145 countries and includes everything from refugee aid to church construction.

One of the pleasures for those of us connected with ACNUSA has been to meet people who are on the front lines of the battle for the faith in some of the world’s most hostile places. In just the last two years, we’ve had the great pleasure of bringing to the United States:

-

Bishop Camillo Ballin, who must have the most remarkable ecclesiastical title in the Church: Apostolic Vicar of Northern Arabia. Bishop Ballin is in the process of building Our Lady of Arabia, a cathedral in Bahrain that can accommodate his large flock: 2.5-million guest workers, mostly from the Philippines.

-

The Melkite Archbishop of Aleppo in Syria, the Most Reverend Jean-Clement Jeanbart, who faces the utterly daunting task of trying to hold on to his community in the midst of decades of war and terrorism that have created one of the greatest refugee crises in world history, and who is dedicated to helping rebuild a viable economic structure in Aleppo that will make it possible for his people one day to return to their homes – what’s left of them.

-

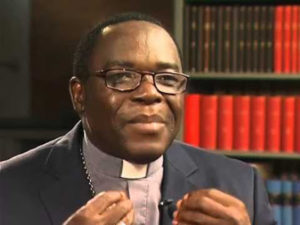

And just this last week, Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah, the Bishop of Sokoto in Nigeria, was able to visit Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C. under the auspices of ACNUSA.

Not to get ahead of myself here, but when I left a small dinner we hosted for Bishop Kukah a week ago tonight, during which there was a lively give-and-take about many issues, I walked to Grand Central Station thinking that our recent roiling discussions about Amoris Laetitia are what one might call a first-world problem. Please understand: the moral theology of the Church and the integrity of the Magisterium are very, very important.

Bishop Kukah, however, lives in the northwestern part of Nigeria where Catholics are a small minority amidst an increasingly aggressive Muslim majority. It’s difficult to imagine what he and his flock are up against, although things are far worse in the northeastern part of the country. That region is home base to Boko Haram, the terrorist group most known in the West for the kidnapping 276 schoolgirls from the Christian village of Chibok of whom 219 are still missing, although it’s known that many have been forcibly converted to Islam, some used as sex slaves, and still others turned into warfighters.

This horror happened some 700 miles away from Bishop Kukah’s diocese, yet it demonstrates what he is up against in Sokoto. Boko Haram is actually a nickname for the group. The official designation is Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad. “Boko Haram,” though, gets to the heart of the group’s mission (if we can call it that), and means – in the blending of Hausa and Arabic – “Western education is a sin.”

The situation in Nigeria’s western states is different than in the east. Still, there is suspicion there too among Muslims about the kind of education that is an important part of Bishop Kukah’s program in his diocese, which covers Sokoto as well as the states of Zamfara, Kebbi, and Katsina.

The education gap in Nigeria is wide; Christians have high literacy rates and Muslims very low. Overall the country is actually about 50-50 in terms of the Christian-Muslim religious breakdown (Islam is concentrated in the north), but Christians tend to hold many more top governmental positions precisely because they’re better educated.

So Bishop Kukah’s goal is to build a boarding school that is open to all young people regardless of religion. The live-in arrangements are essential, not least for security reasons, but also to ensure kids get decent nutrition, a proper amount of sleep, and the experience, Catholics and Muslims together, of amity.

One bold and remarkable insight the bishop has had – and one that was a tough sell to parents in an area in which Christians are such a tiny minority – is the importance of moving schools out of church precincts and into external buildings. Why? To encourage Muslim kids to attend.

And it’s working. As Bishop Kukah explains:

Only last month, I took children from one of our schools in Katsina. . .to meet with the. . .Governor, a Muslim of course. Two of the students had gotten the best results in the entire State in the National Examinations. Both of them, a boy and a girl, were Muslim! You should have seen the look on the children’s faces when they met the Governor and then the Governor’s pride in our school! I persuaded him to offer scholarships to both of them. The girl wants to study medicine, while the young man wants to be an engineer! This is the future!

Please pray for Bishop Kukah, the people of God in Nigeria, and for an end to violence there and throughout Africa.