In the history of Western religion, what we are living through today is, I strongly suspect, a moment historians may eventually label the Era of the Liquidation of Christianity. In its power of liquidation, it is reminiscent of the age of the Protestant Reformation, which might be labeled the Era of the Liquidation of Catholicism, at least when it came to England, Scotland, Holland, Scandinavia, and most of Germany. Beginning in 1517, the old religion was suddenly and rapidly eliminated.

Something similar has been happening over the last fifty or sixty years in the USA, Canada, and Western Europe. The old religion, in both its Catholic and Protestant forms, has largely collapsed. Church attendance has shrunk dramatically. Hardly anybody takes the old Christian sexual morality seriously.

Of course, the elimination of northern European Catholicism in the 16th century wasn’t a total wipeout. Certain residues of the old religion persisted: certain doctrines, rituals, moral standards. The leaders of the Reformation even went so far as to emphasize these residues. They insisted that theirs was an essentially conservative process.

They were not getting rid of the old religion; they were purifying it, freeing it from corruptions, bringing it back to what it had originally been in the days of the Apostles. They didn’t call the process by its correct name, the Protestant Revolution, a name that would have underlined the radical nature of what was happening. They called it the Protestant Reformation, a name suggesting that this was a conservative phenomenon.

And this mis-description of the great religious revolution was not a dishonest propaganda trick on the part of the revolutionaries; it was a perfectly honest belief. One of the most influential of these revolutionaries, King Henry VIII, believed to his dying day that he was a quite orthodox Catholic.

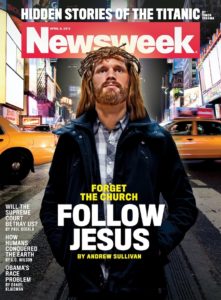

We see something similar today. The makers of today’s religious revolution indignantly deny that they are getting rid of Christianity. They concede that they are getting rid of some of the antiquated forms of Christianity, both Catholic and Protestant, especially its out-of-date moral teachings. But they are preserving its central teaching, the thing that constitutes the essence of Christianity, namely, its teaching that we must love our neighbors.

After many centuries of misunderstanding, a misunderstanding based all too often on hatred of the “other,” we at last have come to understand the heart of the matter. Jesus, that self-educated rabbi and moral genius, taught, by both words and example, one thing and one thing only: LOVE. If Jesus were alive today, he would make his own the motto of the “marriage equality” movement: “love wins.”

What is love, according to post-Christian orthodoxy? It is three things:

1) Above all, it is tolerance. We must respect, and even promote, diversity: all kinds of diversity – racial, ethnic, religious, cultural, linguistic, sartorial, economic, aesthetic, moral, and (especially) sexual. If you disapprove of sodomy or abortion or transgenderism, you are no follower of Jesus. It turns out, then, that the true followers of Jesus are not the old Christians but the post-Christians.

The old Christians talked a good game when it came to love of neighbor; but in actual practice they taught hatred of neighbors who were “different,” who didn’t conform to narrow-minded societal standards.

2) You must cultivate your potential for compassion; at all moments of day or night the affective side of your nature should be permeated by a tone of compassion, a compassion that will leap into action whenever you run across a person who is the victim of intolerance.

3) Since the most effective agency in the present-day world for relieving pain and suffering is the government of great modern societies (e.g., the government of the USA), you should favor the expansion of governmental power and authority, and you should support political parties that promote this expansion.

Post-Christian (or I should say, anti-Christians) fall into two main categories. There are outright atheists; many of these prefer calling themselves agnostics, but in practice they are atheists. They favor an ethic of love and tolerance and compassion; they believe in the ideal of a big government that can solve all the world’s ills. But they see no need to pretend that they are Christians. They think Jesus was a fine fellow; but so were Buddha and Confucius and Spinoza and Florence Nightingale and Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

Then, there are the liberal or modernistic Christians. They don’t believe in classical Christianity, but they still have a nostalgic attachment to the old religion, or at least to the name of the old religion. And they have a special affection for Jesus. They don’t think Jesus was divine, they don’t think he atoned for our sins by his suffering and death, they don’t think he was born of a virgin, and they are very doubtful that he rose from the dead. But they rank him in a higher league than Buddha, Confucius, and the rest. In questions of morality, these modernistic Christians are in full agreement with the atheistic post-Christians.

The relationship between these two kinds of post-Christians, the atheists and the liberal Christians, is like the old relationship between Communists and their leftist but non-Communist “fellow travelers.” The Communists were the less numerous of the two, but they were the more influential; they were the true believers; they were source of leftist ideas. Non-Communist leftists tagged along; they allowed themselves to be used by the Communists.

In the world of post-Christianity, atheists function like the old Communists while liberal Christians function like the old leftist fellow travelers. Sad to say, but it must be said, liberal Christians promote the atheistic agenda while refusing to call themselves atheists.