It’s always a bad sign when you have to keep reminding yourself that some things are still good. Family. Friends. Nature. Music. Poetry. Malbecs. Love. God. (Not necessarily in that order.) Or find yourself repeating, “The times are never so bad but that a good man may make shift to live well in them.” Many people attribute that line to St. Thomas More. I’ve done so several times myself, though I’ve tried – and failed – to find where, if anywhere, he said it.

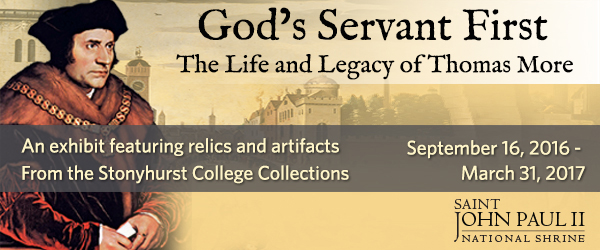

An exhibit about the great English saint opened last week at the John Paul II National Shrine in Washington, sponsored by the Knights of Columbus, with a wealth of artifacts and relics from the U.K.’s Stonyhurst College. A fitting collaboration, because Stonyhurst – which began in exile (as the College of St. Omer) on the European mainland when Catholics were being persecuted in 16th century England – was where John Carroll, our first American bishop, studied and later taught. His cousin, Charles Carroll, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, was also a student there.

Catholics in America today are not, not quite yet anyway, being persecuted or forced into exile. But this whole history makes you reflect on what seemingly impossible things can happen, and happened quickly even in “simpler” times, when a country’s political leadership is corrupted and takes a nasty turn.

Thomas More (and his friend Bishop St. John Fisher) died for what you might call the indissolubility of marriage, even the marriage of a king, and the liberty of the Church. But what might More have meant – if he said it – that we can always “make shift to live well” in evil times?

One place you can start to get an answer is in his little-read, unfinished book, A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation, written (probably with only a piece of coal) in 1534 while he was in prison in the Tower of London, and not published until two decades after his death. Evil times indeed.

It’s a fictional dialogue between an old man, Anthony, and his young nephew, Vincent, set in Hungary just before a Muslim invasion by the Ottoman Turks (a not very hard to penetrate historical smokescreen, behind which More can make observations about England under Henry VIII).

To say that we can live well in evil times – and the times are always more or less evil – is not to say that we can expect to live a tranquil life, or even to go on living at all. Thomas More was the king’s Lord Chancellor, the second most powerful person in the realm, and within a couple of years: had to resign, was imprisoned, falsely convicted of treason, and beheaded.

A nasty turn, but not one that even he would have believed impossible, despite his high station. Twenty years earlier, during a war with France, he joked, truthfully: “If my head could win [King Henry VIII] a castle in France. . . .it would not fail to go.”

Facing his own immediate death in the Tower, More seriously reviews the usual Christian themes about detachment from the world and confidence in God – whatever comes our way. Some of what stings us, he declares, is good for us. It cures our illusions about self-sufficiency and the deep disorder we all display about what it means to “live well,” which we tend to think is mostly a matter of living according to our own whims and pleasures.

At the same time, there are stretches of remarkable lightness of heart in this work, such as we know More showed even right before being beheaded. For instance, he adapts beast stories from Aesop’s fables for Christian purposes. One that is particularly amusing recounts how a scrupulous ass and a self-indulgent wolf confess their sins to a priestly fox – and are each taught, neither be overly scrupulous or self-indulgent. What remarkable self-possession and grace for a man to write that, standing in the shadow of the valley.

Of course, losses of fortune, position, reputation are all – in a sense – steps towards the greatest loss: death. More’s dialogue is in one way an argument with his own fears – which he confessed were strong, especially since the punishments prescribed for resisting the king were brutal. To be “hanged, drawn, and quartered” meant three horrible tortures, one on top of another, before the end. But his book is also clearly meant as a comfort to future Catholics who would, after him, face tribulations and temptations to apostasize.

To such fears, the elderly Anthony gives the firm, traditional reply that we cannot abandon Jesus because our ultimate fate – Heaven or Hell – is at stake. And besides, what kind of ingrate would deny the Redeemer, who denied Himself and suffered such a horrible death to save us?

But then he goes on to more immediately human comparisons: it would be shameful to refuse an honorable death out of fear when even rough soldiers, child martyrs, forlorn lovers, and many other people will give up life for far lesser reasons.

There are few examples in the whole of human history of people consciously facing death with courage – and grace. Socrates amidst the ancient pagans; Our Lord amidst the religious and political turmoil of ancient Israel. One of the strongest arguments about the truth and power of Christianity for many people in the ancient world was how it was able to inspire ordinary men and women to face martyrdom with tranquility, something pagans thought only the very greatest philosophers, such as Socrates, could achieve.

More makes one with that illustrious crew.

As I say, it tells us something about the badness of the times when you are forced to reflections like these. But how good is More’s example. And his advice about preparing ourselves for whatever comes.

And how much better, if we roused ourselves, now, to defend our own religious liberties against state powers, before we just become part of yet another sad chapter in human history.