Populism has been back in style during this presidential campaign cycle. National Public Radio has claimed it is, “one of the most important forces in American politics today. Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump have both tapped into widespread frustrations against the elites and the establishment.”

Throughout our nation’s history, populists have believed their way of life was being threatened by alien forces. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner held that populist agendas were directed toward “survival of the pioneer striving to adjust present conditions to his old ideals.”

Time and again in the 19th century there were such political uprisings – and the aliens then allegedly challenging American values were Catholic immigrants.

The political upheaval in Europe during the Napoleonic wars and the famine in Ireland, hastened Catholic immigration. Between 1790 and 1820 the U.S. Catholic population increased from 35,000 to 195,000 – and to 318,000 by 1830. During the 1840s, some 700,000 Catholic refugees came to America and by 1850, Catholics totaled 1.6 million, 8.4 percent of the U.S. population.

These rapid demographic changes were not unnoticed and brought out the dark side of many who believed that this “barbaric invasion” would destroy America.

In the 1820s, the Anti–Masonic populist movement, dedicated to protecting the common man from secret organizations committed to destroying individual liberties, appealed to agrarian Protestants. Anti-Masonry became a crusade to free rural America from urban domination.

The Anti-Masons especially fixed their rage on Roman Catholics. This was ironic, given that Free Masonry was strongly opposed by the Catholic Church. But for the populists, Free Mason equaled urban, and urban equaled Catholic.

Despising President Andrew Jackson because he welcomed the support of newly minted Catholic voters, Anti-Masons fielded a presidential candidate in 1832, former U.S. attorney general William Wirt of Virginia.

The campaign backfired. Wirt siphoned votes from Whig Party candidate Henry Clay, and Jackson breezed to a second term and cemented immigrant Catholics’ support for the Democratic Party.

In the 1840s, Nativist populists, having painted Catholics as bogeymen, incited violence in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Detroit, Cincinnati, and St. Louis.

Philadelphia was hardest hit because its Catholic population was on the verge of outnumbering Protestants. In May 1844, Nativist mobs attacked Irish neighborhoods, torched churches and a monastery, killed sixteen, and destroyed scores of Catholic homes.

A decade later, a New Yorker, Charles Allen, successfully united populist groups throughout the nation. This conglomerate formed the Know-Nothing Party, which called for stronger immigration laws and prohibition of Catholics from public office.

By 1855, the Know-Nothings boasted control of Delaware, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Kentucky, New York, Maryland, California, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Georgia, and Mississippi. Their greatest triumph was in Massachusetts where they elected a governor and 377 (out of 378) state legislators.

They failed to implement their anti-Catholic agendas, however, because their uneducated legislators had no clue how to run the government, draft legislation, direct it through the maze of committee hearings, or to manage bills on the legislature floor. In Massachusetts, for instance, when Know-Nothings succeeded in appointing a “nunnery committee” to investigate charges that convents were bordellos, they looked like buffoons when the Church pointed out there were no convents in the Commonwealth.

The marshaling of violent gangs, legislative incompetence, bombastic and hateful rhetoric, began to take their toll on the movement. As fair-minded people woke to these threats, the Civil War began to eclipse even imagined threats of papal plots.

Rural Protestants and urban Catholics fought – and died – side-by-side to save the Union and to end slavery. Nevertheless, anti-Catholic populism once again reared its ugly head in the closing decades of the 19th century. This time, the movement united behind the American Protective Association, founded in 1887 by Henry Powers of Clinton, Iowa, to fight “papist hordes.”

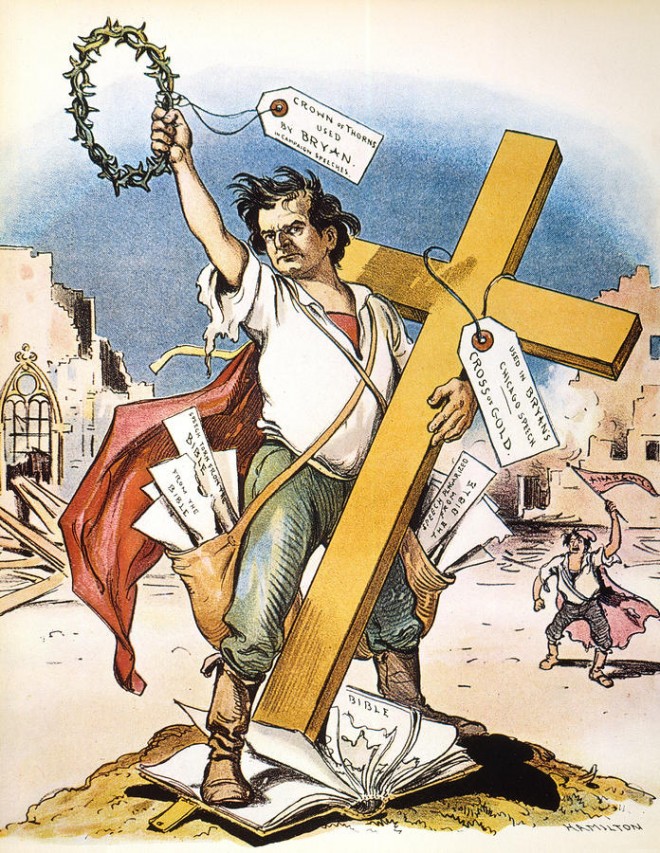

Disgusted with the 1896 Republican presidential candidate, Ohio Governor William McKinley (because he had good relations with Catholics), the APA rallied to Nebraska prairie populist, William Jennings Bryan.

Bryan, a dynamic orator, who possessed the rural and missionary qualities of a tent-preaching revivalist, was brought up in a household that viewed Anglo–Saxons as the supreme race.

He also despised urban America and looked upon eastern cities as “the enemy’s country.” Bryan told followers in Nebraska that he was “tired of hearing about laws made for the benefit of men who work in shops.” As for immigration, he declared he was opposed to “dumping of the criminal classes upon our shore.”

William Jennings Bryan was badly beat by William McKinley thanks in large part to a significant shift in the Catholic vote. Numerous Catholics, while remaining loyal to their local Democratic candidates, deserted the national ticket because they found McKinley more attuned to their concerns than the Bible-thumping, tambourine playing populist Bryan.

The Bryan defeat also crippled the APA. It’s membership declined rapidly, and by 1900 it was a shell of its former self.

There were also populist outbursts in the 20th century led by political demagogues like Louisiana’s Huey Long (1893-1935) and Alabama’s George Wallace (1919-1998). They preyed on the political and economic anxieties of America’s downtrodden.

In our own time, populist movements led by irresponsible extremists on both ends of the political spectrum have embraced “hatred as a form of creed.”

On the extreme right, there are countless charges about “strangers in the land” – Catholic Hispanics, Muslim Middle Easterners, Hindu Indians – depriving “real” Americans of jobs and their fair shot at the American Dream.

On the extreme left, there are populists who condemn our Constitutional Republic as immoral, oppressive, and evil; and denounce Catholics, Protestants, and Jews who disagree with their progressive social agenda, as deplorable fear-mongering racists, homophobes, and misogynists – who are “irredeemable.”

Radical populists, who revel in their own frenzy, are harmful because their campaigns of hate distort deeply held national ideals, and they exhibit what liberal historian Richard Hofstadter referred to as, the “paranoid style in American politics,” which consists of “the qualities of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy.”