Conservative columnist Rod Dreher mentioned in a recent lecture that he knows a high-level executive who believes “it’s just a matter of time” before he will be forced to sign a petition signaling his agreement with the current “politically correct” agenda or lose his job. He is prepared to lose his job.

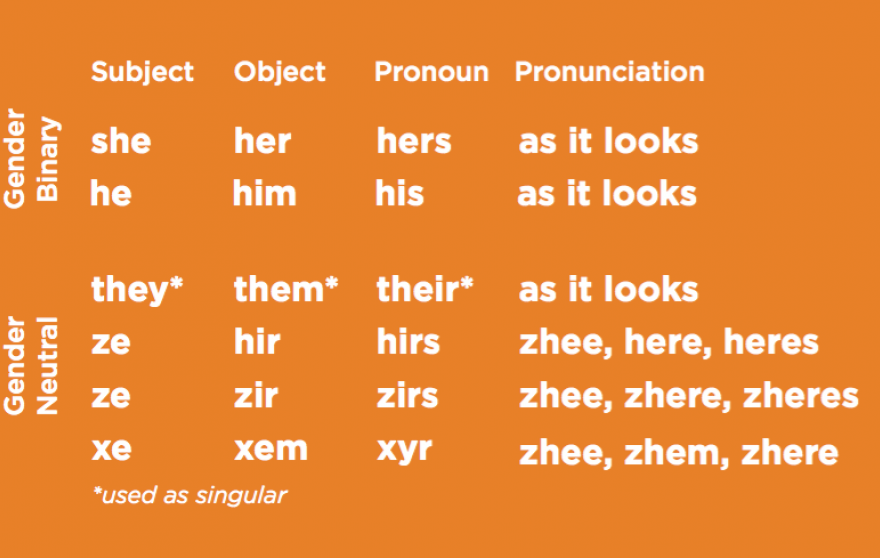

So, too, in less dramatic fashion, I’m sure it’s just a matter of time before someone demands that I agree to employ the new “non-discriminatory” gender-neutral pronouns, ze, xe, zir, and all the rest (discriminatory against no one except those who don’t agree to use them).

When I see students falling all over themselves to make sure they’ve included all the “correct” pronouns in their writing – “he and/or she” did x and y to “him and/or her” – I often write in the margin: “It is perfectly acceptable to do this if you wish, but in my class, it is not required.” Never once has a student continued to use the politically correct verbiage, whether male or female, when informed it was not required. Indeed, I have had any number of students come up to me and express their utter relief: “Oh, thank God we don’t have to go through all that.”

It takes a tremendous effort to force students to write that way, but they will obey if the threat of shaming or punishment is great enough. The moment that the threat is removed, however, the natural manner of expression flows freely again, even if the “correct” way of doing it has been drummed into them from grammar school on.

For now, I allow myself the freedom to allow them this grammatical freedom. When that freedom will be denied me (and them) is in the hands of others. I used to think that we wouldn’t be forced to pay for contraception or abortions on Catholic campuses either, but I was obviously wrong. And if they can order us to open our locker rooms and restrooms to both genders – and they will – then there’s not a long way to go before they demand which pronouns can or can’t be used in “ideologically correct” writing.

I use the term “ideologically correct” rather than “politically correct” (although they are essentially synonymous) because I take it that ideology is at the heart of the matter. Many readers will know the famous example of the greengrocer that Czech writer and dissident Vaclav Havel used in his essay “The Power of the Powerless.” A greengrocer is required by the Communist Party to put a sign in his window that says: “Workers of the World Unite.” They force him to do this, and he obeys, not because either party actually cares about the workers of the world.

Neither the greengrocer nor those who enforce the rule will likely have given much thought to the notion of the workers of the world. Putting the sign in his window is not a sign of concern for the workers; it is a sign rather of obedience to an ideological orthodoxy. Failure of the greengrocer to place the sign in his window is not a sign of disrespect to the workers (of which he, of course, is one) – how would they even know? It is, however, more ominously, a sign of his refusal to accede to the ideology of the ruling class.

So too our own “ideologically correct” language is not primarily about benefitting women or minorities – are they any better off because of decades of language policing? – these are signs of obedience to an ideological orthodoxy. I don’t really harm anyone when I say, “Everyone has his book, I trust.” The problem is, it shows I’m not a person “of the right sort.” To quote the great Strother Martin in the movie Cool Hand Luke, I reveal myself to be a man “whose mind just ain’t right.”

In the meantime, however, while the waves of governmental compulsion still have yet to draw us under and while we’re still merely swimming against the tide, I suggest we need a phrase to keep attackers at bay. One could try clever stratagems such as demanding that, although born male, I wish now to identify as female, but wishing never to “objectify” women, I demand people use feminine pronouns in the subjective case, but never use feminine pronouns in the objective. Thus the proper way to refer to me would be: “She has his own distinctive views on this matter.” I get to choose my own pronouns, right?

Such stratagems are hard to maintain, however, and can’t be used universally. The defensive phrase I have in mind must employ jargon our aggressors understand and be formulated in terms nearly impossible to deny. The phrase must have the effect in the culture that the phrase “No means no” has come to have.

Allow me another example, closer to what I have in mind. I often tell my students that when their peers are assaulting them about their Christian principles, they can always pull out society’s trump card and ask their protagonist: “Are you saying that I can’t live the way I choose according to my personal identity? Are you trying to deny me my personal autonomy?” It’s a cheap trick, but it tends to work. What can one’s attacker say? “Yes, I want to deny you your autonomy”?

In a similar spirit, here’s the phrase I’ve come up with to respond to those who insist on shaming us into a particular form of ideological language conformity. When someone demands we use ze, xe, zir or some similarly baffling verbiage, and that we demand it of our students, I suggest saying: “I’m sorry, but my personal conscience does not permit me to empower that ideology or obey this particular expression of your authoritarian will-to-power.”

Whether it has the desired effect or not, it at least has the great benefit of expressing something true.