It is amusing, or rather it is not, to watch professional purveyors of fake news condemn the blesséd amateurs in the trade.

Or rather they are not blessed: for when the hysterics of the Left allege that there is rightwing blather and nonsense circulating on the Internet – including politically-interested smears and hatchet jobs that cry out for punishment – they can’t help being right. Such villainies are committed by all sides, however, as any reasonably alert reader may prove to himself, by consulting any website with which he disagrees.

This is normal. Politics in the “representative” democracies have been mud fights for as long as we have had information, and the Internet has merely made globally available what was once more locally confined. The optimistic assumption was that voters could sort out the substance from the vapors. Could they ever?

People believe what they want to believe, and by the exacting law of supply and demand, they will be fed what they crave.

We are wrong to think there has been some increase in sophistication, simply because the lies are told on a larger scale. The opposite is more likely to be true. In a small place, culturally homogenous, the lies must be more carefully tailored. Those for a mass audience may be cut from whole cloth, in factories.

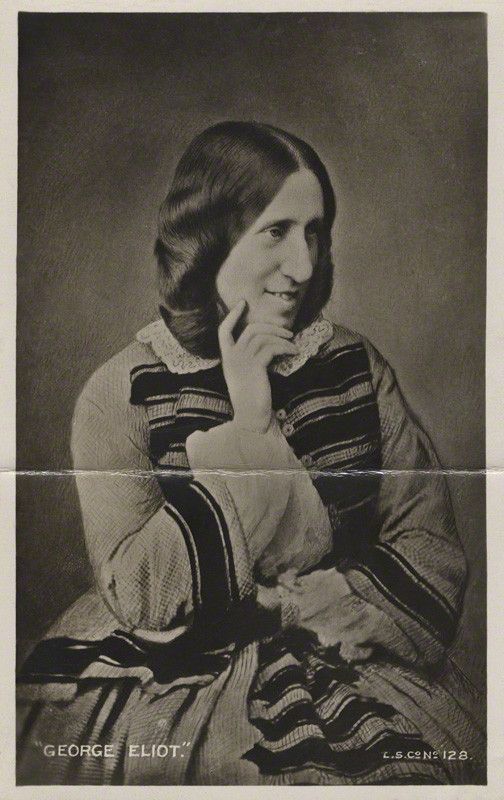

I blame George Eliot. Or rather, I don’t blame her, I think she was a marvelous novelist, and a brilliant observer of small, subtle “facts” or details, of value to any social historian. But like other authors of “classics” from the three-decker era (when novels were published in three hulking volumes), she was up to no good. She was looking to advance an essentially political agenda – as Dickens was, too, from time to time, but she had not his mysterious generosity of vision.

To be lost in the universe of Felix Holt, or even that of her provincial epic Middlemarch, is to be lost in the agenda of a mistress craftswoman. She is conscientious in all her reportage, but she is also consciously undermining received ideas about the moral order, and laying the groundwork for outrages to come. More ingeniously than an Inchbald or a Godwin, she is advancing the revolution that will finally result in democracy as we have it today.

Yet she has the gifts by which an intelligent reader, of any faction, may learn from her. She is still writing for that “intelligent general reader,” who keeps his own counsel. This was a minority in that time, as in this; a remarkably small minority if one counts the press runs.

Perhaps I am ungenerous to pick on her; there is something shriveled in her “cosmic outlook” which disappeals to me. All the grand, earlier Victorian novelists are gnawing upon the brave new world of industrialization, and none is free of a political agenda, though it tends to be expressed without overt party fervor. Eliot is a pioneering New York Times journalist – pretending to be objective.

As that nineteenth century proceeds, in England and the Continent, the three-decker curtain comes down, the novels shorten and become more like tracts. Concessions are made to declining attention spans, in a world now full of tubes and railways. The decadence of the “fin de siècle” and the Edwardians is merely a rehearsal for what will come after the Great War, to a European society now sharply divided not between “aristocrats and peasants,” but between technocratic elites and the masses. The yellow press is in the ascendant, and earnest publishers are being replaced by cynical “press lords.”

The “liberal” and “conservative” impulses are transformed, both adapting to the character of the masses; but these impulses both descend from a fissure in society, which opened earlier in the fallout from the French Revolution.

News, from the golden era of The Times (of London), had been a much different thing – actual information in the daily sheet, of use to those with political, commercial, and intellectual interests, presented concisely and directly; supplemented by long essays and reviews in the high-brow weeklies and monthlies. Now it became, increasingly, at every level, “news you can use” for the freshly literate consumer.

Or rather, news that could be manipulated for the purpose of winning elections, selling goods and then services, and more generally guiding fashions in a vastly expanded “market,” further technologized by the monstrous inventions that emerged from Total War.

Another way of describing the post-modernity, which I instinctively condemn, is as the “advertising age.” All of us must find some way to make a living, and the old settled options of growing food or apprenticing to a craft were fading.

The new serfdom of mostly unskilled “employment” (to more aggressive and ambitious masters) goes with the new sub-literacy. It is supported by a crass, and frequently lying propaganda, that associates these developments with “freedom” and “equality.” (Mutually exclusive concepts.)

What the Internet has done is simply to accelerate this hypertrophic process. The old game of competing plausibilities is now played on a global scale, such that even rival nationalisms and populisms are much of a muchness, only superficially varied, as different “brands” of the same generic product.

All the information we now get from the mass media is sludge, according to me, and bound to be sludge. To some degree the overt lies are of course self-correcting, but seldom in “live time,” when the decisions are made. Who can resist the possibility of tilting the game, in an environment where there are no rewards for virtue?

It is an adage of marketing that the sales effort should make the customer feel good about himself.

Now, consider the Catholic Church, whose attraction is to those who feel badly about themselves, because they sin; and whose adepts are to be vaccinated against the heat of passing “news.” Her task, to my mind, is life-and-death urgent. May she flourish among us. May she make no concessions.