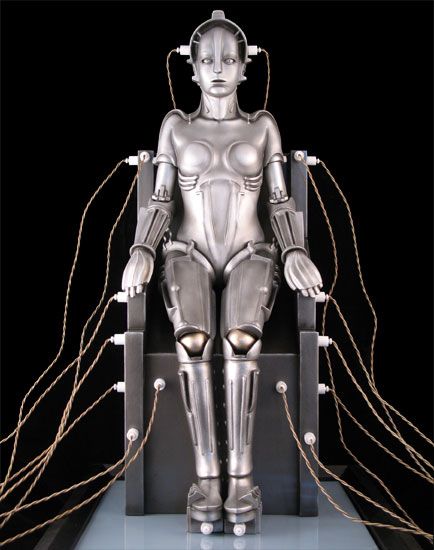

A friend was telling me about a new make of robots.

Now, I was about to write a new “generation,” or a new “breed,” but caught myself in time. For robots, I reflect, do not sexually reproduce – as do humans, for instance, or giraffes. At least, not yet, nor in the foreseeable future. Though one might imagine a marriage of biological and mechanical engineering that would permanently muddy this distinction.

For the moment, however, I think we are still dealing with interactions between robots and men. Robots could be said to be ersatz biological, since many perform chores that, formerly, only humans could perform. They play chess, for instance; and manufacture cars.

Or let us consider the bank machines I have used, to avoid the queue for biological tellers. The messages on their screens are getting cuter and cuter. Soon, I imagine, we will be confronted with animations that will wish us a good day. Or rather, I have already seen a machine that does that, and offers me a mortgage while I’m trying to fetch a fistful of my own cash.

But in Sweden, I learn, they are already phasing out cash. Electronic money has the advantage – from the point of view in Kafka’s Castle – that every particle can be computer-cloud traced. There will be no such thing as a private transaction, and the government will never miss a penny in taxes.

This is a “natural” development: the elimination of money. Already there is really no such thing, and hasn’t been for decades. Before cybernetics had even caught up, we had the new all-embracing term, “credit.” It could still be expressed in paper engravings and base-metal tokens; the idea of “a store of value” lingered. Now it can be gone, for the very purpose of money – to enable private transactions – can be obviated.

One might still own “things,” I suppose. These might perhaps be bartered. But I’ve noticed the stores already computer code products, and can thus foresee a world in which every “thing” of potential transactional value can be tracked like the prisoner with an ankle bracelet, with an alarm and a link to the local police if he tries to take it off. This would probably start as a means of gun control; then proceed incrementally to everything else.

Such innovations have the advantage of indefinitely extending government oversight, which would be good for the bureaucracies, though bad for the bureaucrats. By then, they would all have been replaced by computers. Too, it would be good for business – every expansion of government creates business opportunities in the “mixed economy” – though not good for employees. Who needs staff once the whole world has been inventoried, and items including thieves can be retrieved by drones?

Perhaps I’m getting a little ahead of myself. Reality usually turns out to be “messier” – in the sense of, harder to control – than anyone expected. There may still be need for a few public and private commissars to make some judgment calls.

But back to that new make of robots. Granted, my information comes only from a human in one of these outdated “bars” – where one may still drink, though not smoke, and must increasingly mind one’s comments. But my interlocutor seemed to know what he was talking about, and what he said was plausible.

These will be the robots who interview you at the airports, or border crossings, or anywhere else. You sit in front of the robot and it (I almost wrote “he”) asks you multitudes of trivial questions. Various sensors and sophisticated analytics determine if you are lying, while consulting a central database to determine whether you might be wanted for something. (Illegal bartering, for instance? Excessive sugar consumption? Removing your social security implant? Blowing up a market in Baghdad?)

Eventually, I imagine, it could be linked to an electric fryer, to dispose of those who give the wrong answers, on the same principle as the “safe” new tests that can not only spot a Down syndrome fetus, but wipe it out into the bargain.

Again, I may be getting carried away, the way truck drivers do when they hear that their vehicles will be automated within, say, ten years. And I was going to add, all getaway cars from bank heists, until I realized it may no longer be possible to physically rob a bank, in less time than that.

Too, I might be accused of projecting a dystopic fantasy, were it not that we are already living in one, albeit with inadequate technology.

Finally, it could be said that I am telling gentle reader nothing new. I am surprised, for instance, how many seem to grasp that the jobs Mr. Trump will take back from Mexico are scheduled for automation in the very near future. And that, we already have car factories that can work mostly “lights out” – i.e., human workers not needed even to dust the machines.

“In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread,” it is written. But we already have visionary proposals for a minimum income, regardless of employment, so perhaps that will go by the board.

Once everything is automated the people may be kept alive by government programs; though I can’t see why. Except for inefficient handicraft production, they will be completely redundant. No need even to harvest them for organs, in the Red Chinese manner, as there’ll be no demand.

What interests me is an earlier passage in that Book of Genesis, third chapter. I go not to the beginning, but only so far back as, “I was afraid, because I was naked, and I hid myself.” In the original it was God whom Adam and Eve feared and hid from.

But in the sequel – the current vision of progress – it will be the omniscient state from which we are trying (quite pointlessly) to hide.