The village of Chelm, near Poland’s border with Ukraine, is seen in Jewish folklore as the place where an angel, assigned by God to carry a sack filled with foolish souls for distribution across the globe, suddenly stumbles, dumping them all onto the village. One of them, it turns out, finds employment sitting at the gate waiting for the promised Messiah to come. When he complains to the village elders that he isn’t being paid enough for the job, they agree: “Yes, the pay is too low. But consider: The work is steady.”

There is humor here, to be sure, and the reader smiles on hearing it. But at the same time it masks a bitter sadness that survives the telling. For Jews especially, it is a dark and terrible tale. And while it may seem funny to see a fool more or less forced to wait forever, the fact that every other Jew sees it that way, that they too are fools to wait, only deepens the sense of pathos.

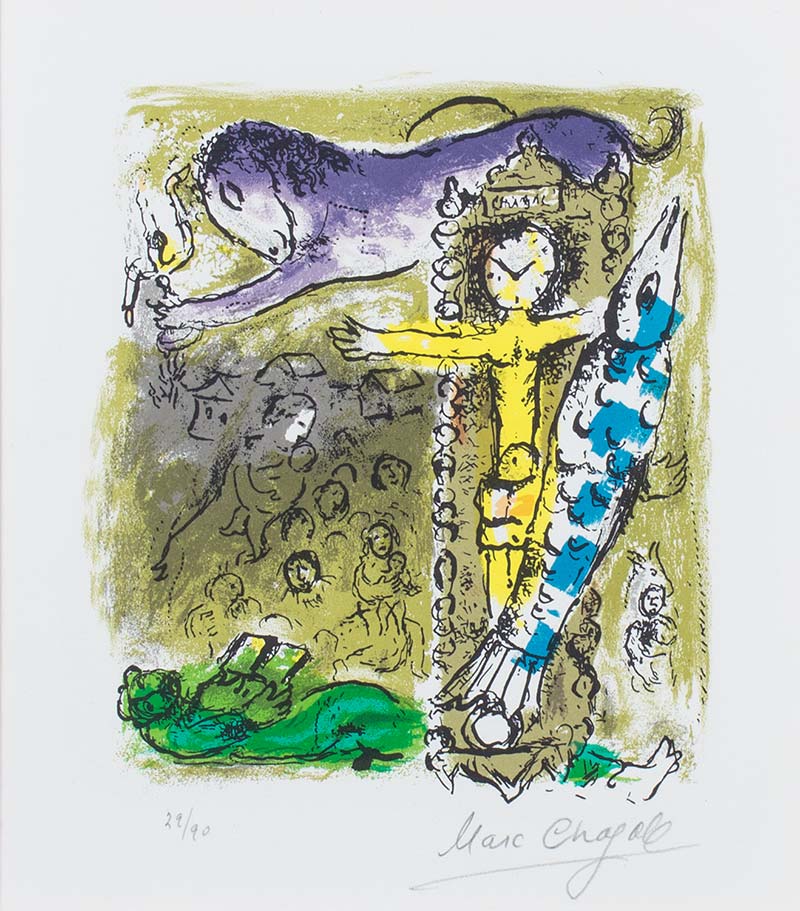

Here the Christian must make an effort of will and, practicing the sympathy to which our elder brothers are entitled, imagine the sheer strain imposed on those who, century upon century, await the arrival of One whom our own faith assures us has already come. Because, in truth, they had been the first, the very first, to hear the message; the first therefore to be given the promise of deliverance that the Messiah would surely come. (“Behold, a Virgin shall conceive and bear a son; and his name will be called Emmanuel.” Isa. 7:14)

Indeed, the Apostle Paul presses us to remember the high destiny of his kinsmen – who have become our kinsmen as well inasmuch as, spiritually speaking, we are all Semites – that because they are the Israelites, “to them belong the sonship, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the worship, and the promises; to them belong the patriarchs, and of their race, according to the flesh, is the Christ, who is God over all, blessed forever.” (Rom. 9:4-5)

So what can the Jews do when, by their reckoning, God never shows up? All that hope they’d foolishly invested, what do they do with it now? I mean to say, here they are, the privileged People of the Book, recipients of an absolutely singular assurance from God himself, to rescue the whole of Israel from bondage to sin and death.

How odd of God to choose the Jew, we are told. And yet for all that their oddity keeps getting in the way, endearing them to no other tribe or nation on earth, they nevertheless remain God’s dearest possession, irrevocably the choice he has made. Besides, what other beachhead save that of Judaism has God established whence to mount his re-conquest of the world?

Only now, of course, God having failed (seemingly) to deliver, they think in terms of betrayal, of having been party to an act of divine treachery, conceived by the same God who first brought them into being. What could possibly prove more damaging to a people’s trust than the prospect, in their eyes, of God refusing to honor the very covenant he had made?

Surely the temptation to harness all that energy and idealism, all the longings that shaped Israel’s soul, to turn it all into politics and ideology – “immanentizing the eschaton,” as it were – must seem nearly impossible to resist. Hence the great Zionist tug among modern, secularized Jews, who, having decided to substitute geography for God, now turn their backs on the Law and the Prophets.

They no longer wait for God to come to them. Instead, many run after the same fleshpots that have pretty much co-opted every other tribe and nation. Thus do they eviscerate their own identity, annealed in an intimacy initiated by God with Abraham and the children promised to him.

The glory of Israel, we need to remember, was never merely an ethnic or racial affair. It was always religious, an identity suffused with the sacred otherness of a God who espoused himself to a people. And that for two millennia all the revelations of the living God were entrusted to them. Can such a thing be said of any other race or people in the history of the world?

And not only words were spoken to Israel. The unheard of enfleshment of God’s own Word took place within Israel as well, within the womb of the Jewish maiden Mary. Is there any other people who can say that from the very loins of its life there once sprang into human being the Eternal Word and Son of the Father? The great theologian Jean Daniélou comments:

In this alone there is a greatness that staggers our imagination and reason. All other earthly greatness is passing. The great empires of antiquity have sunk into oblivion; their monuments – attempts to defy time – are merely tombstones of bygone civilizations. The great powers of today will decline in their turn, but Jesus Christ will live eternally and will be eternally Jewish by race, thereby conferring a unique, eternal privilege on Israel.

For us, who believe Christ came to redeem the human race – who, in fact, will genuflect on this day in grateful observance of the fact – let us not forget that, while it is true that from the flesh taken by the Son of God all humanity has been remade, it is also and equally true that it was the human race that first made Christ.

Which precisely means that the flesh of the Son of God was freely taken from a young Jewish maiden named Mary. Who remains the true and everlasting figure of the hope of both Israel and the Church.

“May this living fountain of hope,” writes Luigi Giussani, “be every morning – every morning – the most gripping and tenacious meaning of life possible. Nothing in the world is sure except this.”