One way to make a society cohere, to keep it from falling apart, is to put all power in the hands of a highly centralized political party that controls the state, the military, the judiciary, the police (including secret police), newspapers, radio and TV, the entertainment industry, education, sports, youth organizations, labor unions, industry, agriculture, banking, transportation, all real estate, and many other things. This is how the Soviet Union was held together for many decades despite the USSR’s great linguistic and ethnic diversity, a diversity (pace the multiculturalists) that tended to pull it apart.

As soon as the tight central controls were relaxed during the Gorbachev years, everything quickly fell apart, and what had been a single country became fifteen independent countries.

Another and better way to hold a society together is by means of a religious-moral consensus. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, this was the way the United States was held together. Americans had a common religion, Protestantism. Of course, there were some Catholics in the country, but they were poor and not very important socially or politically. And there were a few Jews, mostly of German provenance. They were not as poor as the Catholics, but they were even less important politically. Everybody who really counted was Protestant.

There were, to be sure, many different kinds of Protestants, and they differed on certain theological points and matters of church governance. But with the exception of Unitarians and Universalists, they agreed on more things than they disagreed on. They agreed on the King James Bible, the Trinity, the Divinity of Christ, the Atonement, the Resurrection, the Ten Commandments, Heaven and Hell, and many other things – including the proposition that the Church of Rome taught a false and perverted Christianity.

We should never forget that anti-Catholicism was a “glue” that helped to unify early American Protestantism, which in turn helped to unify early America. The first important contribution Catholicism made to the USA was to serve as an object of fear and contempt.

But in time the numbers and importance of Catholics and Jews grew, and it became increasingly clear that the USA could no longer think of itself simply as a Protestant country. And so we learned to think of ourselves as a “Judeo-Christian” country, a nation of three religions that had much in common. All three accepted the Bible – even though they had three different Biblical canons.

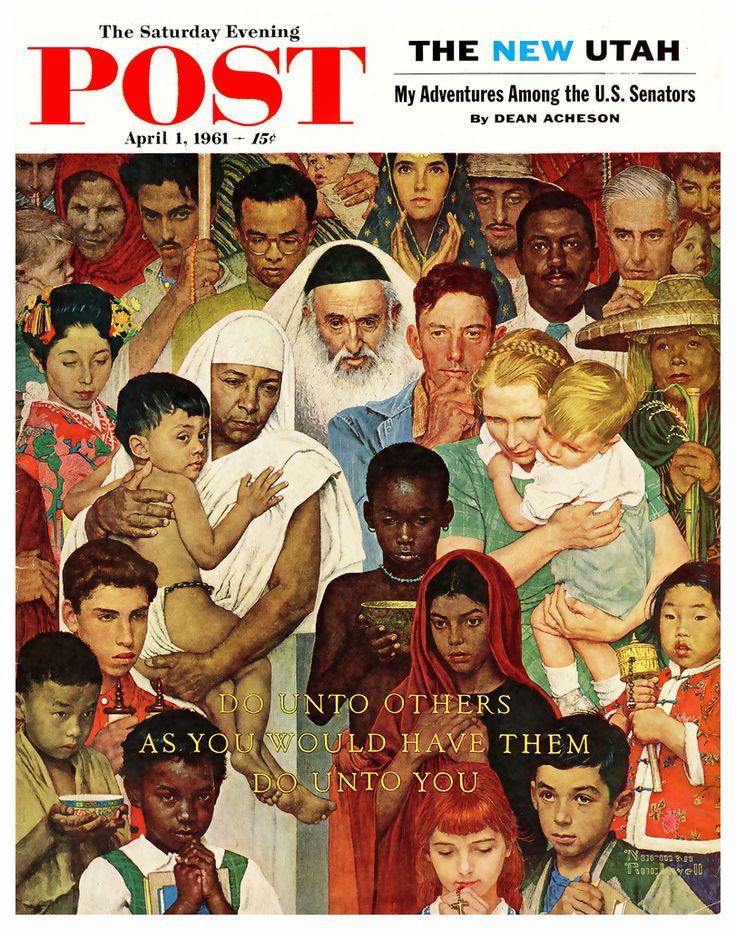

We had found the formula for assimilating non-Protestants. Using this formula, there seemed to be no good reason the United States could not evolve into an Islamo-Judeo-Christian country or even into a Hindu-Islamo-Judeo-Christian country. The broader the religious consensus became, of course, the thinner it would become: a mile wide and an inch deep. All the same, we would still have a national religious consensus. As it had done in the beginning, when the common faith was Protestantism, so an amended common faith would continue to hold the nation together.

About fifty years ago, however, during the turbulent 1960s, a new factor emerged, a group that could not be assimilated to an ever-expanding religious consensus. I refer to a variety of atheists – outright atheists, agnostics who are virtually atheists, and religiously indifferent people who never trouble their minds about the question of whether or not God exists. These atheists and near-atheists are still a minority of the nation’s population (between 10 and 20 percent if we identify them with the “nones” in Pew Center reports), but an influential and rapidly growing minority. Many of them have been brought into the atheist camp as a byproduct of the sexual revolution. If one is going to reject the Bible’s code of sexual morality, why not reject Biblical religion altogether?

But while you can have a Judeo-Christian religious consensus, and maybe even an Islamo-Judeo-Christian consensus, you can’t very well have an Atheistico-Judeo-Christian religious consensus. (In a curious book written in the 1930s, A Common Faith, the highly influential American philosopher John Dewey advocated precisely this, a common “religious faith” shared by theist and atheist. They could both speak of “God,” but one of them would mean by this word an existing reality while the other would mean a not-yet-existing ideal. Even the most ardent of Dewey-ites, and in those days there were many of them, thought this proposal nonsensical.)

If we can no longer have a national religious consensus, however, can’t we still have a national moral consensus? And isn’t a moral consensus more important for purposes of social cohesion than a religious consensus? Don’t atheists and theists both agree that murder and bank robbery are wrong and that kindness is right?

Yes, but what about abortion? Almost all atheists believe abortion to be morally permissible while almost all conservative Christians (I mean Evangelical Protestants, orthodox Catholics, and Mormons) believe abortion to be not just wrong, but very seriously wrong.

“True,” the defender of the idea of an American moral consensus will say, “but abortion is only one thing. We cannot expect to have perfect agreement. As long as we agree on almost everything, that’s enough. Indeed it’s more than enough.”

This answer does not comfort me. For one thing, abortion may be the single most conspicuous thing atheists and conservative Christians disagree on, but it’s not the only thing. We disagree on a wide range of sexual issues, on a growing list of euthanasia issues, and on foundation-of-morality issues. For another thing, even a single disagreement is enough to destroy national unity if the point of disagreement is big enough. American unity was once destroyed because Northerners and Southerners disagreed on the issue of slavery even though they agreed on just about everything else.

Besides, I fear that Dostoyevsky may have been right when he said that if God doesn’t exist, “everything is permitted.” I suspect that we have not yet understood what seeds of moral wickedness lie hidden in the spirit of atheism.