A recent column by Anne Killion, “More Ominous Signs for Football,” in the San Francisco Chronicle, ended this way: “One reader was much more succinct: ‘Outlaw that disgusting sport.’ This debate isn’t going away. But, little by little, high school football might be.” Baseball is probably faring even worse than football. Lacrosse is on the rise. If football is abolished, we may see the return of its ancestor, rugby, a game that still flourishes in many former British colonies.

The logic seems clear. With no high school football, we get no college football. With no college football, no professional football can continue. The link between generations will have been broken. Fathers will not have taught their sons how to play.

For a number of reasons, largely due to injuries and subsequent insurance costs, with some ideology mixed in, I suspect that most high schools will not field football teams in a decade or so. Is that a good thing? I doubt it. But good things now have no preferential claims on existence.

On a fall Friday evening, when I was in high school (Knoxville, Iowa), the biggest town event was the football game. On Saturday morning, the local merchants around the town square would go over the game of the previous evening. We all awaited the report in the local weekly paper. If one of our players was recruited by the Iowa Hawkeyes or the Iowa State Cyclones, or even by Central College in nearby Pella, it was the local talk.

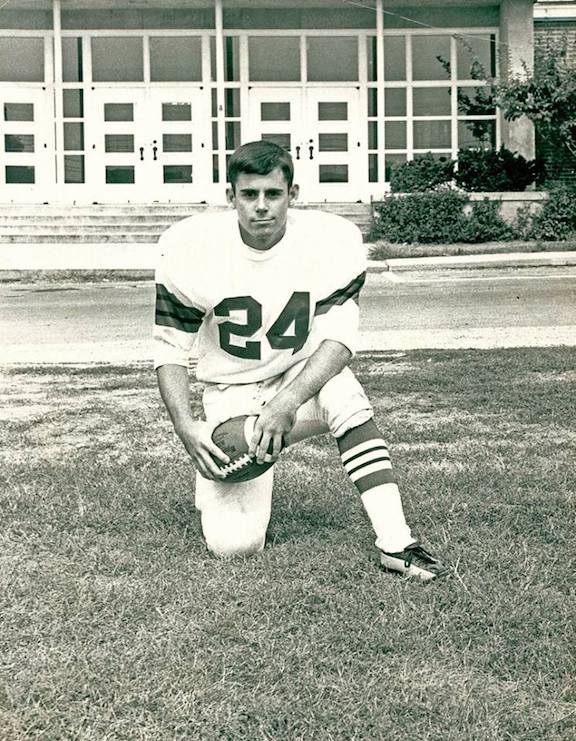

With some pride, old codgers talk about their past football glories and injuries. Serious injuries, even deaths, do, no doubt, occur on the fields of play, not just in football. The prospect of a risk-free sport or a risk-free life is not always a happy one. The only way not to be injured in some way is not to do anything, and that may not work either.

Football is a sport for boys and young men. Many things are learned in athletics that can only with difficulty be learned elsewhere. The world’s most widely played and watched sport is soccer (futbol, in Spanish). The possibility of concussions is the main sticking point of the opponents of football at any level. I could never see why soccer’s helmet-less “headers” were not more dangerous. But statistics seem to show that soccer impacts are not as forceful as in football.

I remain one of those men who are glad to see fall season roll around. Still when Nile Kinnick’s Iowa Hawkeyes defeated Notre Dame by a score of 7-0, in 1939, it was a crushing blow to us few Catholics in Knoxville.

Some folks like to think that football and sports in general are a quasi-religion. But I side with Brad Miner. Sports are, or should be, the one place where a man can escape the politicization of everything else, including religion.

Sports, as Aristotle maintained, are not as frivolous as people often assume. Aristotle had only the Olympics to watch, but the Olympics are well worth watching. As I have remarked elsewhere, games and matches are things worth watching for their own sakes. It is not an accident that games take us out of ourselves to concentrate on what is happening “out there.”

We really do not want to “do” anything at a good game, unless we are making money by selling beer or hot dogs. In that case, we are not there to see the game. Games, as Aristotle said, are less “serious” than the contemplation of being. But that does not prevent us from seeing in them what we mean by something that fascinates us because it is gripping. The nearest an average man gets to contemplation is in fact the watching a good game. What is there rivets one’s attention simply because it is going on. We are caught up in the action unraveling before us.

So what if, in the end, the score is Iowa 7/Notre Dame Zip, the Giants 5/the Dodgers 3, or Real Madrid 2/Juventus 1? What is played out before us causes us to behold something besides ourselves. We do indirectly realize that we are the beholders. Few human experiences come closer to explain the aura surrounding divinity than these.

Many a young man will acknowledge that his best teacher in high school was a coach. As they reflect on it, the coach taught them more than football, but that too. We should not be surprised at this.

If we take football away from the culture, we will not be doing ourselves a favor. We will deprive ourselves, I suspect, of one of the few natural experiences that lead us to appreciate what it means to speak of “higher things,” of things that take us out of ourselves, of things that exist out of nothing “for their own sakes.”