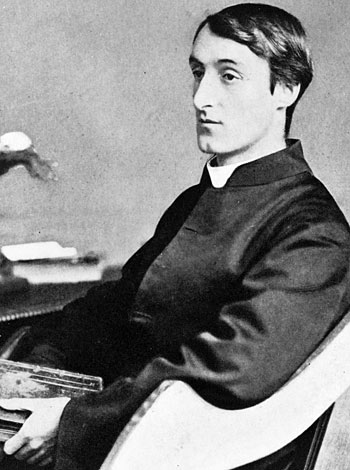

The notice of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s death in the Register of the English Province states “he had a most subtle mind, which too quickly wore out the fragile strength of his body.” The Catholic convert, Jesuit priest, and profound poet died of typhoid fever at only forty-four, after a long period of overwork and depression in Ireland.

Slight of frame, melancholic, and with a nervous constitution, Hopkins led a short yet extraordinary life. The images we have of him show a man looking at life from the outside; serene yet nervous, aloof yet tortured. Alongside his poetry, letters, journals, and sermons offer us detailed insights into his personality and creative process.

Hopkins’ poetry is radically original and idiosyncratic. He used “sprung rhythm,” common in early English poets like William Langland, as in this from “God’s Grandeur”:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

His work influenced various modern movements in poetry. But though he wrote all his work before the close of the 19th century, until his university friend Robert Bridges edited a first edition of his poetry in 1918, Hopkins remained virtually unknown.

His greatest poetry is profoundly Catholic. It conveys the deep longing of the soul for God, as well as the heights and depths of his own religious feelings and experiences. Pied Beauty and God’s Grandeur rank among his most well-known pieces. The Wreck of the Deutschland is a feat in itself; a long, sprawling poem about the shipwreck and drowning of Franciscan nuns fleeing Bismarck’s anti-Catholic Kulturkampf.

It was at Oxford that Hopkins first began to take up Catholic ideas. An undergraduate Classicist at Balliol, he entered a city reeling from the impact of the Tractarians. John Henry Newman had crossed the Tiber in 1845, and his presence still seemed to haunt the streets and lanes. Moving in High Church circles, Hopkins’ diaries already reveal fasts and penances. A crucial Oxford companion was the aristocratic Digby Dolben, whose death from drowning at nineteen would have a profound impact on Hopkins’ life.

Hopkins gradually became convinced that all Christian truth is contained in “the Real Presence in the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar. Religion without that is sombre, dangerous, illogical.” This would be at the centerpiece of his conversion. It had become impossible for him to remain within the Anglican Church.

Hopkins knew that conversion meant risking alienation and estrangement from his family and friends. The atmosphere at Oxford was still one of deep distrust and enmity towards Catholics. The Thirty-Nine Articles were required of undergraduates until 1854, and College officials would keep records of students attending Mass in the city. Attitudes in the wider society were even worse; Catholics were still very much seen to be in league with a “foreign Prince,” and there were both political and social consequences to converting.

His changing beliefs, particularly on the Sacrament, could not be ignored; “there’s none but truth can stead you. Christ is truth.” A letter from his parents from just before his conversion exists at the Bodleian Library, in which his mother exclaims “O Gerard my darling boy are you indeed gone from me?” In 1866, Newman received Hopkins into the Church at the Birmingham Oratory.

From that moment, it seemed destined that he would enter the Jesuits. Hopkins’ personality demanded extremes, and if he was going to convert it meant no moderation. He knew the life of a Jesuit would be hard for him physically. He was also fully aware of the impact the decision would have on his family and friends, given that anti-Jesuit prejudice was still rife in English society.

The constant conflict that Hopkins felt between his faith and his art came to a head when he entered the novitiate. He “resolved to give up all beauty until I had His leave for it” and burnt his poems; he did not really write verse again for seven years. If he had not sent Bridges some material, his pre-Jesuit work would have been lost forever.

The physical and nervous issues that Hopkins suffered throughout his life were central to his person. Letters written during his extended periods of depression convey helplessness, and in some cases even glimpses of madness.

The “Sonnets of Desolation” were written in the midst of a breakdown in Dublin, where he felt cut adrift and isolated; “to seem the stranger lies my lot, my life.” The poems are visceral, and almost shockingly dark. He even spoke of suicide to Bridges, and in a famous line described himself as “Time’s eunuch.”

Through all this, he created beautiful responses to the darkness – and puzzlement about the world – that come to almost all of us at some point in life:

Thou art indeed just, Lord, if I contend

With thee; but, sir, so what I plead is just.

Why do sinners’ ways prosper? and why must

Disappointment all I endeavour end?

Wert thou my enemy, O thou my friend,

How wouldst thou worse, I wonder, than thou dost

Defeat, thwart me? Oh, the sots and thralls of lust

Do in spare hours more thrive than I that spend,

Sir, life upon thy cause. See, banks and brakes

Now, leavèd how thick! lacèd they are again

With fretty chervil, look, and fresh wind shakes

Them; birds build – but not I build; no, but strain,

Time’s eunuch, and not breed one work that wakes.

Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots rain.

Faith saw him through to the end.

Hopkins risked everything to enter the Church, and suffered greatly for it. Before he died, he repeated “I am so happy. I am so happy.” This should give us pause for thought. Truly, in spite of everything, “the Holy Ghost over the bent/ World broods with warm breast and with ah! Bright wings.”