Both Testaments of Scripture contain passages in which we are admonished to hate something, like evil, but not to hate our brother. We are familiar, perhaps too familiar, with the adage: “To hate the sin but love the sinner.” This aphorism can easily leave the impression that my sin is floating out there totally independent of me, who, in the meantime, remains pure as the driven snow. No sin disconnected from a sinner can be found. Moreover, we are definitely well advised to avoid some sinners or, at least, to deal with them most gingerly.

When Aristotle treats anger, itself a good thing, he talks about controlling or not controlling our passionate response to what is dangerous or wrong. We usually overdo it. But not to be angry at evil things is a vice. Some things ought to anger us.

Hatred is the emotional response to our recognition that some specific thing is wrong in the world. Tell me what you hate and I will tell you what you are. And if you tell me that you do not hate anything because nothing is wrong in the world, I have an even clearer picture of what you are – that is, hopelessly naïve.

Here, I am interested in the relatively new phenomenon known as “hate language.” Few things are potentially more pernicious, especially when governments and institutions get into the business of defining and enforcing it. “Hate language” and freedom of speech are clearly in bloody conflict with each other. The same folks who were once interested in pressing the limits of free speech – such that most anything could be said with impunity – are now the same people who, in control of the culture, want to suppress any speech not to their liking.

Where did this “hate language” business come from anyhow? Its origin was in the now largely successful endeavor to overturn the moral structure of civil society. Generally speaking, this transformation was accomplished through the deft usage of “rights talk.” What was once called, on rational grounds, a disorder or vice became first tolerated, then finally a “right.” Once it became a “right,” then for anyone to call it a sin or evil became a slander, an attack on transformed human dignity and pride.

Human language has a purpose. It is accurately to define, then name, what in reality it designates. If we come to use the same word for two very different realities, we have to deduce from usage to what reality we are referring. If marriage means both the relation of male/female and male/male, the reality to which the word marriage refers does not change. One is not the other.

At this juncture, “hate language” arrives on the scene. Since the law now claims that both marital arrangements are “the same,” we no longer are free to state that they are not the same. It causes pain to people to hear that what they do is or is not a marriage. The very statement that they are not the same is judged a civic disorder that must, in the name of preventing turmoil, be forbidden. We can find ourselves ostracized or put in jail for stating what is true and giving arguments for it. Free speech, which was designed to state the truth of things, is no longer permitted. Truth is now what endangers society.

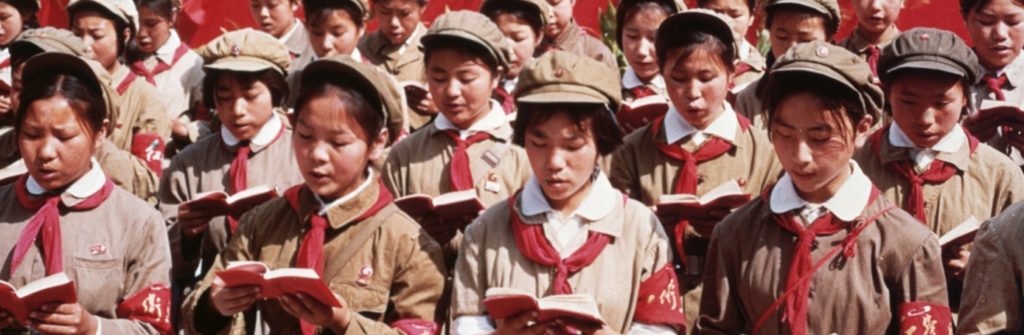

When this situation is universalized, we find that we have to provide places where people are protected from even hearing anything that would question either the rightness of their own choices or the civil law that has now claimed jurisdiction over all of our speech. A most odious feature of totalitarian societies was to set up listening posts or to have children tell what their own parents said in private. This same phenomenon has arrived among us. It is now gussied up in the image of protecting the victims from the hatred of those who refuse to accept the new “rights” regime that insists that its law is the highest and only law in the land.

In discussing law, Aquinas asked: Whether we should have a law that forbad all vices? At first, it seems like a good idea. In fact, it is a terrible idea. Aquinas understood that giving such power to the state would imply a divine knowledge. It would also do away with that freedom to err and to be wrong that allows us to chart our own destiny.

Aquinas knew that some vices had to be dealt with, otherwise we would be in a state of war with each other. But to empower the state to rid us of all vices would require giving it absolute power, something too many politicians covet. Citizens would lose that arena of freedom and intelligence in which they are to carry out their own decisions. “Hate laws” ultimately stem from the modern democratic state’s endeavor to change human nature.