When I first went to work in the book publishing business back in the mid-1970s, I was given charge of an area called “Special Markets,” which included, among other retail outlets, health food stores and religious bookstores. I was a Catholic in a company that was largely Jewish and Catholic but included some Protestants. However, most were really secularist.

This may have been the reason the Christian books we published were listed as “Inspirational.” Looking back, I see this as an early version of “I’m spiritual, but not religious,” a cancer on the Body of Christ that keeps metastasizing.

I was reminded of this as I screened Same Kind of Different as Me, the new film of the bestselling book of the same name. (The book has one of those long and unnecessary subtitles: A Modern-Day Slave, an International Art Dealer, and the Unlikely Woman Who Bound Them Together.) The movie has a religious sensibility but without having much to say about religion. It’s identified as a “faith-based drama.” Also, the inevitable: “Based on a true story.”

It starts at the end, which is a good place to begin. Ron Hall (Greg Kinnear) is writing a memoir, and the whole movie, except for a couple of scenes, is basically a flashback. I’m not sure why the book needs to be referenced when we’re watching the story on screen; director Michael Carney (who co-wrote the script with Mr. Hall and Alexander Foard) thinks it’s relevant. But this isn’t exactly Zola writing J’accuse.

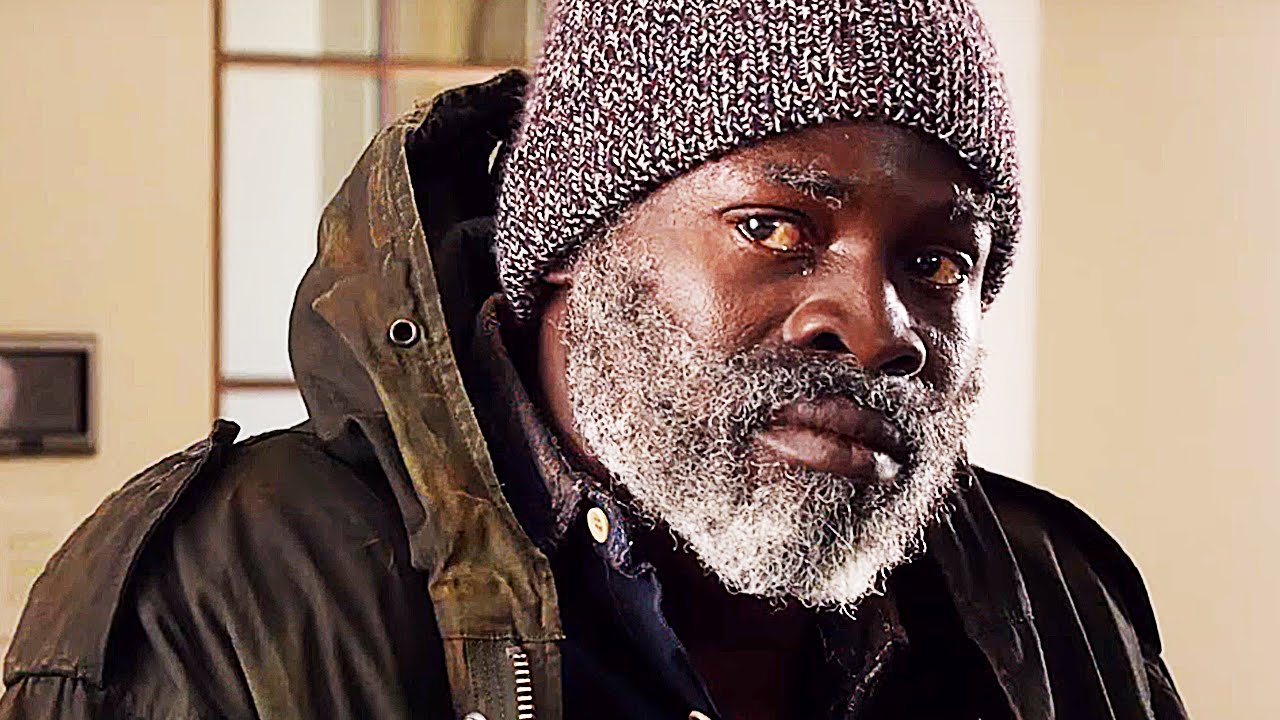

Deborah Hall (Renée Zellweger) and husband Ron are going through a rough patch. She encourages him to come to the local soup kitchen to help out. She’s found spiritual satisfaction in doing unto others. There they meet homeless folks, who mostly make Ron’s skin crawl, until Denver Moore, a violent, half-crazed, baseball-bat-swinging lunatic played by Djimon Hounsou, bursts in. Long story short: it’s beauty and the beast, except there’s no romance between Deborah and Denver. Neither is there any chemistry between Zellweger and Hounsou.

Mr. Hounsou hails from Benin in West Africa, and – although he has been working in British and American films since 1990 – his Louisiana/Texas sharecropper accent leaves something to be desired. But (as I’m given to reminding readers) movie acting is all about the eyes, and Mr. Hounsou’s are startling when he glowers and captivating when he smiles.

His performance and Mr. Kinnear’s work well together, and a few other actors’ work shows Mr. Carney at his best. The director knows how to reveal character by putting his camera tight on a face and letting the actor act, which leads to some marvelous, tender moments, as when Chef Jim (Thomas Francis Murphy) explains how he ended up cooking at the “mission” soup kitchen – a scene Mr. Carney handles with just the right restraint to give it real power. It presents a stark contrast with the scene in which we first meet Denver Moore.

Equally good is Ann Mahoney as Clara, a homeless woman fallen into prostitution. She has a scene of transformation that is very moving.

And then there’s Jon Voight, whose career I’d thought a few years back was on a steep slope towards Sharknado-style TV movies. But he shows once again that, at 78, he is arguably our best character actor, perhaps the best in a generation, although here he stands in as the embodiment of racism and ignorance. We know this, because he’s the only one who drinks something other than sweet tea.

When the camera and the narrative pull back, though, things fall apart. Way too much screen time is taken up by shots of Ron in an old pale-yellow SL-class Mercedes-Benz driving down Texas roads in autumn: lovely in cinematographer Don Burgess’s images – but not at all relevant.

What the story purports to be is akin to what we saw in The Blind Side (2009). The Blind Side was the story of the transformation through friendship of a very large, very talented, very poor, and very lost black teenager and a very small, very caring, very rich, and very forceful white woman. (Sandra Bullock won the Best Actress Oscar.) But in that film one really saw the ups and downs and many-faceted interactions between the two.

One of the lengthy, meaningless scenes in Same Kind of Different as Me has Miss Zellweger and Mr. Hounsu sitting next to one another. The actors seem to be preparing themselves to act but seem never to get the call to “Action!” There they sit. Waiting. It seems to be an attempt to substitute emotion for thought and action. Silence can be powerful on film, but it can also be insipid. I can’t think of another film in a dozen years that falls back so unsteadily upon reaction shots – less than subtle pleas to the audience to emote along with the actors.

I blame Steven Spielberg, as competent a director as we have, who yet must have his actors’ faces cue the audience to emotions the viewers surely already feel: awe at seeing dinosaurs or aliens.

And as good as Mr. Carney can be with actors, he seems largely to have overlooked Miss Zellwegger, whose performance suffers. Part of the problem is that her natural voice is similar to the character she played in Chicago, Roxy Hart. Her accent is good (she’s a real-life Texan), but she has a tendency to sound coquettish. Marvelous for playing a Billie Dawn perhaps; not so wonderful for a Marguerite Gautier.

There are some non-denominational, inspirational films that Catholics might love to see – Chariots of Fire (1981) is certainly one, but Same Kind of Different as Me isn’t one of them.

___

Same Kind of Different as Me is rated PG-13 for some cussin’.