Even though a Starbucks is across the street now, the Mission at San Juan Capistrano still stands out. The architecture, the grounds, the ambience: there’s a reason why it is called the “jewel of the California Missions.” Wherever you rank it, though, it’s something special. And a simple plaque just outside its entrance caught my attention recently. It draws together several threads of “ancient history” that have resurfaced with great urgency.

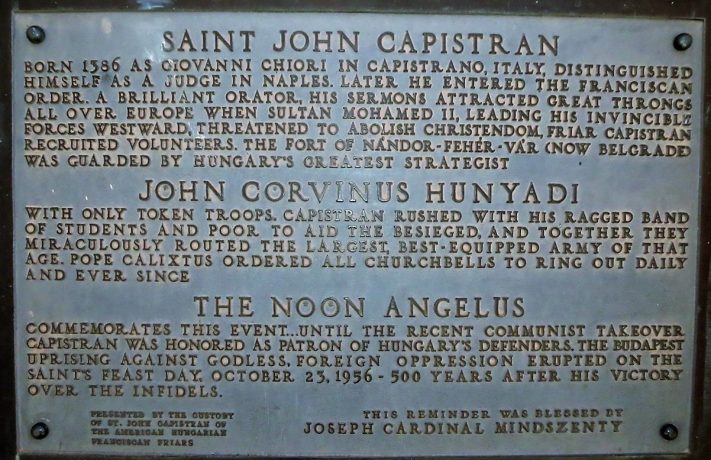

People mainly associate this Mission with the annual return of the swallows. But let’s back up and consult the plaque: just who was this Mission named for? He was an Italian judge before joining the Franciscans and becoming a noted and well-traveled orator. It was the 1450s; Constantinople had just fallen. As Sultan Mehmed II was encroaching upon the heart of Europe with Turkish forces in tow, the 67-year-old friar, at the behest of Pope Callixtus III, sprang into action.

He recruited volunteers and teamed up with John Hunyadi, Hungary’s great military strategist; together they made their stand at Belgrade. Greatly outnumbered, they nonetheless “miraculously routed the largest, best-equipped army of that age.” He survived the siege, only to fall to the bubonic plague a few months afterward.

So St. John of Capistrano takes his place among the figures who were crucial in thwarting the military advance of Islam at decisive moments. The present time qualifies as another such moment. Indeed, the unprecedented inroads into the heart of Europe through hijra – conquest by way of migration – far surpass those of Islam’s many previous armed forays.

Today, Hungary’s Prime Minister wonders aloud if there will continue to be a Christian Hungary, or a Christian Europe; for this, he mainly earns accusations of xenophobia and Islamophobia from people who imagine his concern – not massive uncontrolled immigration – is the problem. Meanwhile, elsewhere in Europe, governments play down rampant rapes, no-go zones, or Saudi-sponsored radical mosques. London’s Muslim mayor perfectly expressed the attitude: terrorism, he’s said is, lamentably, just part of life in the big city now.

Back to the plaque: it notes that the 1956 Hungarian uprising “against godless foreign oppression erupted on the Saint’s Feast Day (October 23) – 500 years after his victory against the infidels.” Cardinal Mindszenty, who had been imprisoned by the Hungarian Communists on charges of treason, was granted asylum at the U.S. Embassy during that uprising. He was confined there for the next fifteen years, but eventually visited Mission San Juan Capistrano – and blessed the plaque.

One more interesting coincidence: after Capistrano’s victory, Pope Callixtus ordered the daily ringing of Church bells and “ever since the noon Angelus commemorates this event.” This might seem to be a pious afterthought, but the Angelus, of course, is a prayer that celebrates the Incarnation – the furious rejection of which joins Mohammed and Karl Marx at the hip.

It is precisely on the metaphysical plane – in the doctrinaire denial of the Incarnation – that we find the deepest commonality (even prior to totalitarianism and expansionism) between the Muslim mind and the Communist mind – and yes, even the “Liberal” mind.

Modernity can essentially be defined by its practical indifference to the radical event of the Incarnation. Somewhere along the line, the Incarnation ceased being seen as the decisive turning point in the history of the human race. History itself – Forward! – took its place as the “event” – as yet unrealized – around which everything must be oriented.

Rousseau, that grand Patriarch of the Left, thought human nature itself was on a historical journey, but mainly regarded man as good; the stubborn persistence of evil, therefore, he had to attribute to defects in society, which would need some heavy reworking in order to usher in paradise on earth. Thus his thought aligned with that of Mohammed in discarding the notion of original sin. And if man does not stand in need of redemption, the Incarnation makes no sense.

Yet it is ultimately only on account of the Incarnation that Jacques Maritain – the influential 20th century Catholic champion of human rights – could write that the soul of any person is of greater value than the entire physical universe. That is no mere platitude. Ponder it next time you happen to find yourself people-watching.

The Muslim could never wrap his mind around that sublime consideration. The postmodern liberal – for all his reflexive chatter about rights – can’t really either: because in devaluing the Incarnation, he takes both the “Universal” and the “Human” out of “Universal Human Rights.”

The universality derived from the view of man as created in the imago Dei and reinforced in singular fashion by the Incarnation contrasts sharply with the actual divisiveness that we see on many sides these days – not the sham “divisiveness” commonly used in public disputes as a rhetorical tactic, but some form of us vs. them: Muslims vs. all non-Muslims; rich vs. poor, black vs. white, strong vs. weak, woman vs. man, the sexually liberated vs. hateful prudes, one privileged “identity” vs. another.

As a result, we have come to classifying specious and downright nefarious, inhuman things as “rights.” So “progress” requires the death of tens of millions of persons who would have populated the future.

In other words, it is built into these ways of thinking that some members of the universal human family must be systematically targeted (in varying degrees): that is one pretty big reason why the monumental significance of the Incarnation cannot be solely a private matter – contra the inward-oriented and sentimental view of religion we have so thoroughly adopted from Rousseau.

Our attitude towards such a weighty matter as the Incarnation may look like merely an odd belief of a dwindling number of Christians. But as history shows, it’s much more than that and affects the whole human race.