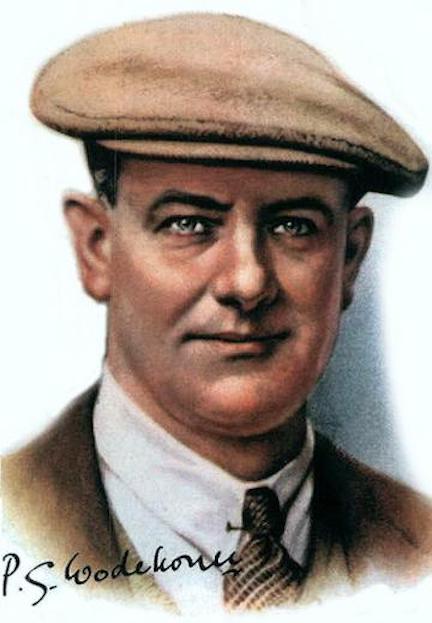

P.G. Wodehouse’s novel Uncle Dynamite concerns the exploits of Frederick Altamont Cornwallis, the fifth Earl of Ickenham. After a dispiriting session with his erratic Uncle, Lord Ickenham (alias Uncle Dynamite), Reginald “Pongo” Twistleton-Twistleton gloomily reflected on the nature of the human mind: “But the human mind is capable of strange feats. You never know where you are with it.”

What about these “strange feats” of the human mind? One of the many odd things it can do is to understand a pun, a very improbable feat when you come to think of it. To grasp the point of a pun, to be able to laugh at it, you have to keep three or four different things in your mind at the same time. You must not only keep them present before you, but compare the different meanings of the words. To accomplish this feat, the points of the pun and the person knowing them in his mind cannot be solely material.

Early in the book, Wodehouse provides an example of a perfectly awful, yet funny, pun. It seems that Lady Ickenham keeps pretty close tabs on the Fifth Earl. When she is away, however, Lord Ickenham hustles off to London for a good time, to his nephew Pongo’s digs. He drives the proper young nephew batty.

The Lord has just seen his wife to the boat at Southampton for a visit to the “West Indies.” He was recounting this scene to Bill Oakeshott, a friend of his nephew Pongo.

When the Fifth Earl said that Lady Ickenham was off to the “West Indies,” Bill quizzically responds: “Jamaica?” To this, Lord Ickenham replies: “No, she went of her own free will.”

When the Fifth Earl said that Lady Ickenham was off to the “West Indies,” Bill quizzically responds: “Jamaica?” To this, Lord Ickenham replies: “No, she went of her own free will.”

Now to catch the humor of that quick repartee, one has to know his West Indies geography. He has to know both about free will and about the clipped English expression: “Did you make her go?” = “Ja make er?” You would have to know something about slang to realize how the name “Jamaica” and the phrase “Did you make her?” can sound alike. Unexpectedly seeing these things together, one has to laugh.

While this instance may not be the most amusing pun ever concocted, even to understand it, corny as it is, one has to hold all its component items together at once and, simultaneously, see their relation. To be a human being means to have a faculty whereby we can see such incongruities and why they might be related. We have, in other words, a spiritual power that can do these things. It comes gratuitous with the gift of our being what we are. We can observe how it works in our very selves.

Why do we have minds? Not everything in the universe has one, though everything in the universe seems related to one. Aristotle tells us that we have minds that are capable of knowing all that is. We also have senses through which various aspects of the physical world are conveyed to us. We can tell that the same thing has a taste, a smell, a touch; we can hear and see it. We have minds so that what is not ourselves can become known to us. When we know something, we change, we grow. The thing we know does not change. We become what we are not. We become more than ourselves.

At first sight, to be a human being means that we are not something else but only ourselves. The problem then becomes: “How is it possible to remain ourselves and still ‘be’ everything that is not ourselves?” The answer is by knowing them, what they are. It turns out that we are not, by being ourselves, deprived of the world that is not ourselves.

The mind can seem to be a jumble of things with no order to them. As Wodehouse said “You never know where you are with it.” Yet, on inspection, we see that we can identify the things that we immediately know. We see that some things have weight, others are relations, still others tell us about time and place.

While we are individual, finite beings, we likewise possess minds that enable us to know what we are not. We are not deprived of the universe because we are ourselves. The human mind looks out on what is not itself. We do not want to become something else. Yet we become aware of the vastness of what is not ourselves. Our minds make us aware that these many things are also given to us to know.

The “strange feats” of which the mind is capable teach us that, because of it, we are open to all that is, even to the cause of being itself. We know “where we are” with our minds when we realize that we have minds so that the truth of things does not escape any of us.