I started reading Pope Francis’ new Apostolic Constitution, Veritatis Gaudium (“On ecclesiastical universities and faculties”) and – honestly – got stuck on the first part of the second sentence: “For truth is not an abstract idea, but is Jesus himself.” Francis’ opening statement on truth vs. abstract ideas reminds me of Aquinas’ consideration of the question whether the object of faith is a proposition or God. Francis seems implicitly to be putting us before a similar choice. But Aquinas argues that this choice is a specious one. Our faith is in both propositions and in the reality of the divine Word, Jesus Christ.

What, then, IS an abstract idea? Francis doesn’t say so, but I think we can surmise that abstract ideas may be considered propositions that we assert to be true, and the context doesn’t determine the truth-status of the proposition. So, abstract ideas are abstract truths. For example, “The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.” (John 1:14) “Christ is risen from the dead.” (1 Cor 15:20)

Other examples of abstract truths that are asserted may be taken from the Pastoral Letter of First Timothy: “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.” (1:15) “God our Savior. . .desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth.” (2:3-4) “For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.” (2:5) “For everything created by God is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving.” (4:4)

The truth-status of these propositions is such that they will be true always and everywhere. It is not the context that determines their truth-status. A doctrinal proposition is true if – and only if – what that proposition asserts is in fact the case about objective reality; otherwise, the proposition is false. It is not the context that determines the truth of the proposition that is judged to be the case about objective reality. Rather, reality itself determines the truth or falsity of a proposition.

Abstract truths, such as the ones from First Timothy, are part of the content of faith. Isn’t our faith, then, in both propositions and in the objective reality of the Person of Christ?

In what sense, then, is faith a way of knowing divine reality, and how, as Romanus Cessario, O.P., asks, “can propositions serve as true objects of faith, even though the act of faith finds its ultimate term in the divine reality?” Cessario adds, “For Catholic theology, the act of faith reaches beyond the formal content of doctrines and attains the very referent – ‘res ipsa’ – of theological faith.”

In Aquinas’ account of faith, he argues that “the object of faith may be considered in two ways. First, as regards the thing itself which is believed, and thus the object of faith is something simple, namely, the thing itself about which we have faith; secondly, on the part of the believer, and in this respect the object of faith is something complex, such as a proposition.” Aquinas understood this matter well. Yes, realities are in the knower according to the mode of the knower, according to Aquinas, but in the knower knowledge of the truth in man is propositional.

Still, Aquinas does say, “Actus autem credentis non terminatur ad enuntiabile sed ad rem” [The believer’s act (of faith) does not terminate in the propositions, but in the realities [which they express].” While it is true to say that the ultimate term of faith is not a set of theological formulas that we confess, but rather God himself, it is also the case that for Aquinas articles of faith are necessary for knowing God. Aquinas explains: “We do not form statements except so that we may have apprehension of things through them. As it is in knowledge, so also in faith.” In other words, one knows primarily God Himself but as mediated in and through determinate propositions.

This is precisely what Francis’ statement misses. But not the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “We do not believe in formulae, but in those realities they express, which faith allows us to touch. ‘The believer’s act [of faith] does not terminate in the propositions, but in the realities [which they express]’. All the same, we do approach these realities with the help of formulations of the faith which permit us to express the faith and to hand it on, to celebrate it in community, to assimilate and live on it more and more.” (§170)

If we are to understand the nature of the Christian faith, we need to do so in light of the teaching of the Apostle Paul who calls us to believe with one’s heart and to confess what one believes. (Rom 10: 9) The then-Lutheran theologian, the late Jaroslav Pelikan, informs us of a twofold Christian imperative – the creedal and confessional imperative – that is at the root of creeds and confessions of faith. Faith involves both the fides qua creditur—the faith with which one believes – and the fides quae creditur – the faith which one believes.

A full Biblical account of faith involves knowledge (notitia), assent (assensus), and trust (fiducia). Indeed, normatively speaking, these are three elements of a single act of faith involving the whole person who commits himself to God in Christ and through the power of the Holy Spirit. Minimally, however, faith involves belief, and to have a belief means that one is intellectually committed to the whole truth that God has revealed.

Furthermore, faith involves holding certain beliefs to be true, explains Aquinas, because “belief is called assent, and it can only be about a proposition, in which truth or falsity is found.” Moreover, the fides quae creditur is the objective content of truth that has been unpacked and developed in the creeds and confessions of the Church, dogmas, doctrinal definitions, and canons.

Is faith in propositions or in God? In Catholicism, it is in both.

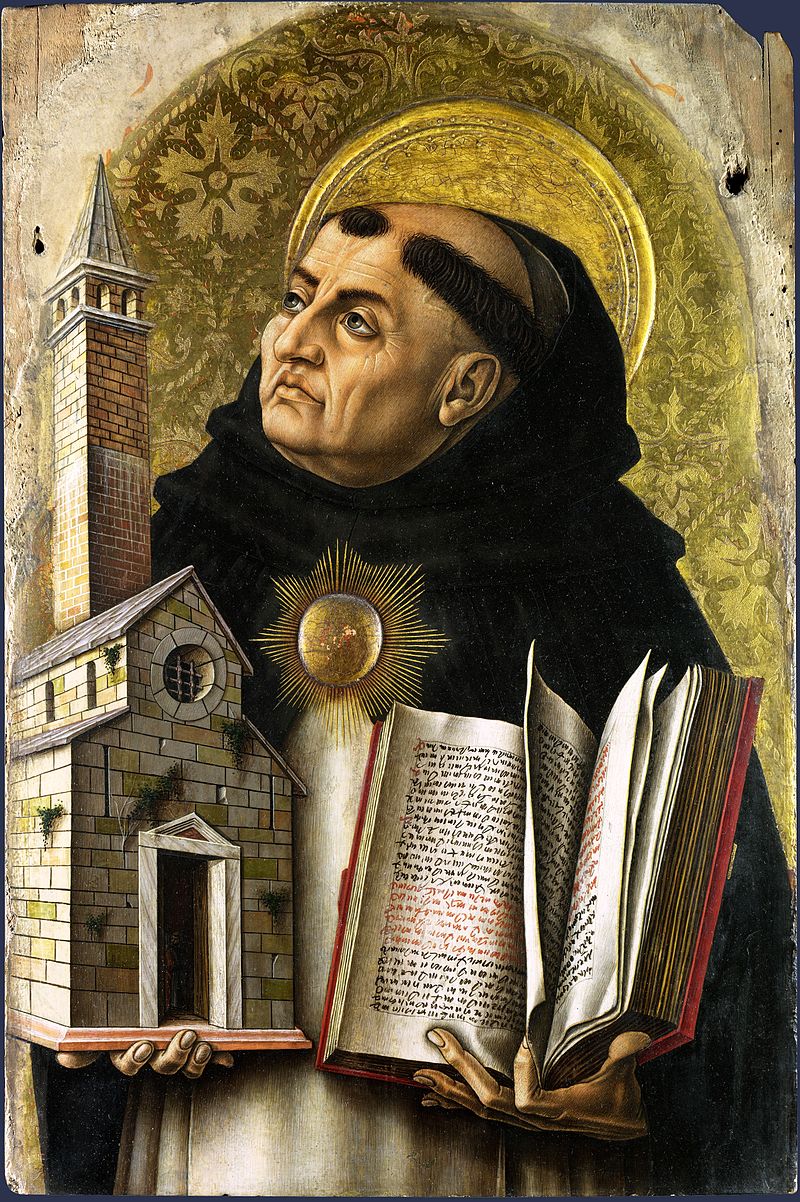

*Image: Saint Thomas Aquinas by Carlo Crivelli (part of the Demidoff Altarpiece), 1476 [National Gallery, London]