Regular TCT readers know of my passion for good movies, the corollary to which is my distaste for bad ones. Most recent Biblical films (those released since TCT began ten years ago this coming June) have usually been less than praiseworthy, and some readers have complained that it’s un-Christian of me to pan any work whose Christian filmmakers, after all, mean well. But that’s not the way this reviewing thing works.

In any case, it’s very good to be able, finally, to have a film I can recommend wholeheartedly, although it’s impossible for me not to be a little querulous.

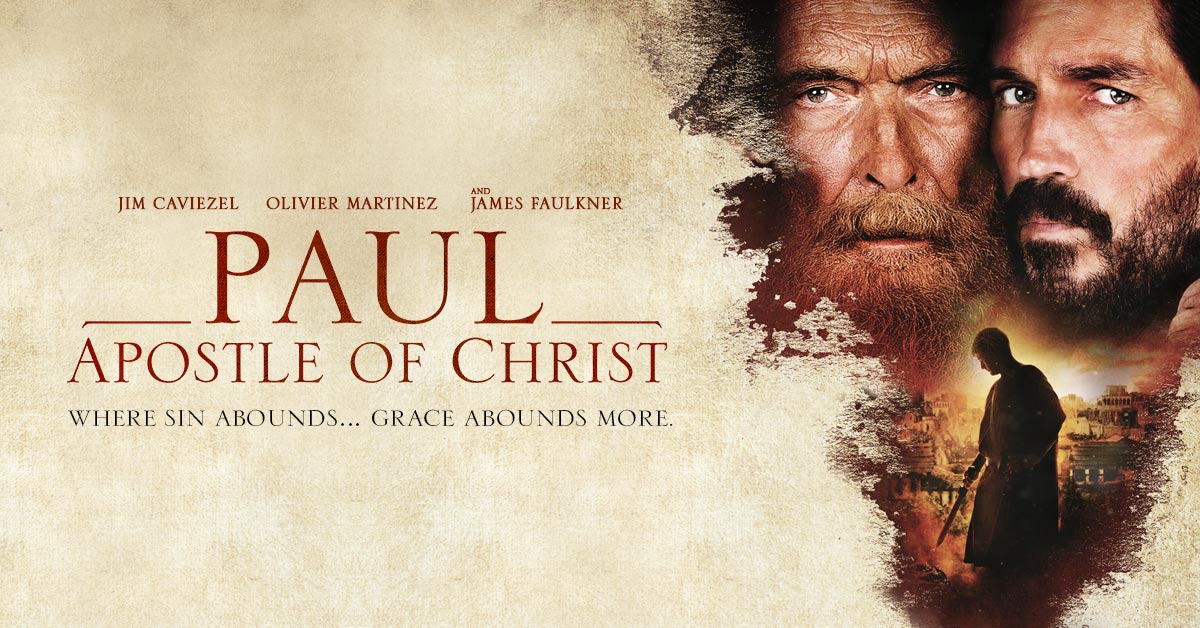

Andrew Hyatt’s Paul, Apostle of Christ is a winner overall. It’s a faithful, faith-based retelling of the Book of Acts (with some bits from Corinthians, Romans, and Timothy) that manages to overcome its narrow, theater-like presentation and its dependence on narration and exposition. Mr. Hyatt knows more about moviemaking than I do, yet I’ll suggest that – for next time – he remember that in directing and screenwriting (he ably does both on Paul) rule #1 is: show don’t tell.

In a recent interview, Mr. Hyatt, said: “We just stay with Scripture as the only source material.” That’s fine, as far as it goes, and many viewers will be pleased to recognize God’s word when they hear it. It’s just that Paul is overly wordy. In fact, much of the action of the film takes place “off stage.” We hear about the persecution of the Early Church, but we don’t see it – not much of it anyhow.

And now my usual carp about darkness: Paul is yet another film that employs low lighting and shadows to stretch a limited budget. To be sure, Paul (James Faulkner) is incarcerated in the bowels of a prison near Rome’s Capitoline Hill, sentenced to rot there under the watchful eye of the prefect Mauritius (Olivier Martinez) until it pleases the Emperor Nero to chop off his head. Paul has prayer to sustain him.

And he also has visits from that dear and glorious physician, Luke (Jim Caviezel), who is determined, as any good reporter/historian would be, to get the great man’s story down on parchment, a sequel of sorts to his Gospel. In essence, Paul’s life is the second-greatest story ever told.

It’s dark underground, and it’s dark in a world lit at night only by torches and candles. But the darkness and the talkiness are present in this film instead of the spectacle that once made Biblical films epic, colorful, inspirational, and fun.

What puts Paul, Apostle of Christ on a tier below The Passion of the Christ, but well above all other recent Biblical films, is its cast, especially Faulkner and Caviezel, who manage to portray courage, piety, and brotherhood in ways that seem rooted in an ancient time and place, yet utterly contemporary as well.

Mr. Caviezel brings a delightful journo twist to Luke: he’s out to get a story, and he shares with Paul exactly how he’ll frame it. He peppers Paul with questions that draw the older man out, forcing him to dredge up painful memories, especially ones from the stoning of Stephen up until his own conversion on the way to Damascus.

Mr. Faulkner can sometimes seem almost too restrained, too still for the Paul we know from Scripture, the evangelist with legendary oratorical skills and profound mood swings. Many no doubt have personal views about what sort of presence Paul must have had, and again, to be fair, the Paul of Paul is imprisoned and awaiting death.

As he’ll dictate to Luke in his second and final letter to his former companion, Timothy: he has fought the good fight, finished the race, and kept the faith. But he’s weary now. It’s over. He knows it. He’s ready to go Home. And although we never hear the great man preach, we are witness to his faith and his love. Faulkner’s eyes, which in other films have been menacing, burn with love for Christ. He very much resembles the great Rembrandt’s vision of Paul (see below).

When Luke’s faith seems to falter, Paul’s faith flares, and he threatens Luke . . . with love. He fairly assaults him with it.

Other Christians are burning too: hung up around Rome, doused with some sort of accelerant, and set aflame, punishment for their alleged complicity in Nero’s Great Fire of 64 A.D. This persecution seems quite intentionally meant in the film to be an ancient mirror of contemporary terror in places such as, yes, Damascus, and many of the Roman Christians in Paul are forced to become migrants.

An interesting, non-Biblical, subplot involves the ailing daughter of Mauritius, the jailer. Mauritius has his household gods – all good Romans did – but when prayers to them fail, he takes Paul’s advice and brings Luke to see the girl. I’ll say no more except to note that there follows another iteration of a hand brushing through wheat stalks in a field, an apparently now irresistible Roman meme begun nearly two decades ago in Gladiator.

It’s harvest time, as it was in Genesis 8:22 and is in Revelation 14:15: God told Noah just before the rainbow: “As long as the earth endures, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night will never cease.”

And John heard the temple angel call out: “Use your sickle and reap the harvest, for the time to reap has come, because the earth’s harvest is fully ripe.”

Scripture doesn’t tell us how Paul died, but his end is sensitively and convincingly portrayed in the film; his entry into heaven done with elegant simplicity.

____

Paul, Apostle of Christ, in theaters today, was shot on location in Malta and is rated PG-13 – the usual “may not be appropriate for younger viewers”: children die; men are beaten and torched. With Joanne Whalley and John Lynch as Priscilla and Aquila, real pros doing fine work, and an intense, heartfelt performance by Antonia Campbell-Hughes as Irenica, the wife of Mauritius.

The Apostle Paul by Rembrandt van Rijn, c. 1657 [National Gallery, Washington, D.C.]