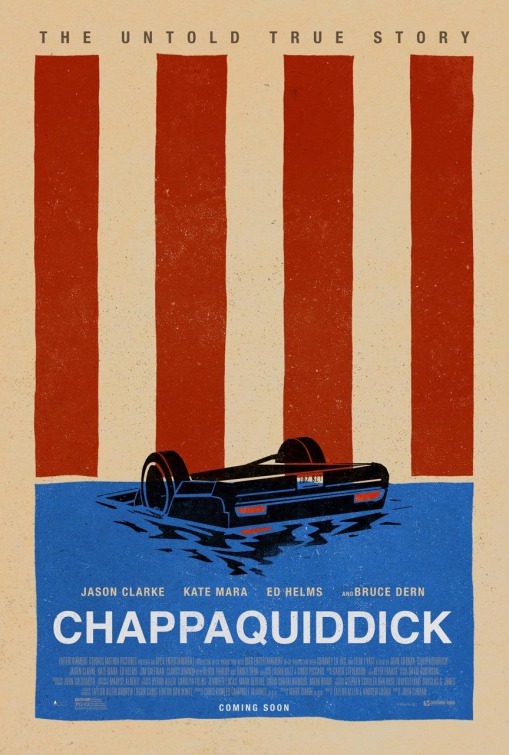

Directed by John Curran with a script by Taylor Allen and Andrew Logan, Chappaquiddick – which opened last Friday – tells a story most people over the age of 60 will recall. Whether or not it will appeal to younger generations I can’t say, although the studio has a hashtag for that: #thisreallyhappened.

To jog your memory: In the early morning hours of July 18, 1969, the junior U.S. senator from Massachusetts, Edward M. Kennedy (hereinafter, Teddy), left a party in the company of a former aide to his late brother Bobby, and – almost certainly under the influence of alcohol – drove his car off a wooden bridge and into a tidal pond. Teddy managed to escape from the sunken automobile; his passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, did not. It’s unclear whether she drowned or suffocated inside the Oldsmobile Delmont 88, probably the latter (she may have survived for four hours).

What happened next is both unclear and yet damning. In the film, we see Teddy sitting on the bank of the pond in the immediate aftermath of the crash. Then we see him walking along the road that leads back to the beach-house party where six – now five – single women (the “Boiler Room Girls” of RFK’s ’68 presidential campaign) and six – counting Teddy – married men continue their rather sad revels. Teddy (brilliantly and flawlessly played – with minimal but effective makeup – by Aussie actor Jason Clarke) tells an aide to fetch his cousin, Joey Gargan (superbly played by Ed Helms). Then Teddy climbs into the backseat of a waiting car. He says: “I’m not going to be president.”

Together with a former U.S. Attorney, Paul F. Markham (Jim Gaffigan), the three return to the scene of the accident. Gargan and Markham strip down and dive into the dark water, fruitlessly attempting to save Mary Jo. Teddy then insists that they commandeer a rowboat to take him back to Edgartown on the mainland so he can return to his hotel. Gargan and Markham, both lawyers, urge him to call the police as soon as possible. Instead, Teddy calls his father, Kennedy patriarch Joe, who whispers one word of advice: “Alibi.” Teddy’s first contact with the police came nine hours later.

The timeline of events portrayed in the film is unclear: we don’t know exactly when the car crashed (probably between 12:30 and 1:00) or when Teddy arrived back at the party. The film fails to note that he walked passed at least four houses on the way to reunite with his friends and – as they became – co-conspirators, or that each of these houses had telephones from which he could have called for help.

Instead – assuming that Mary Jo was dead – Teddy went into damage-control mode.

There follows a meeting back in the famous family compound in Hyannis Port in which veterans of the JFK Administration, the RFK campaign, and Teddy’s own senatorial staff try to overcome Teddy’s fecklessness in order to preserve his future and, above all, the Kennedy legacy. It isn’t easy.

Teddy has recklessly instructed an aide to tell the New York Times’ James Reston, one of the era’s most astute reporters, that the senator is unavailable for comment due to the concussion he received in the accident and the sedatives prescribed to treat it. Reston knows you never give sedatives to a concussion victim. Then Teddy decides to attend Mary Jo’s funeral wearing a neck brace, which he clearly didn’t need.

In both cases, the press pounced.

As to the concussion claim itself: Teddy was never actually examined by a doctor.

The whole episode was one of cowardly dissembling. In his statement to the Edgartown police, Teddy claimed to have made multiple attempts to save Mary Jo, although it’s unlikely he did, and there’s no doubt that his principal concern had quickly become saving his reputation, which the Hyannis Port “brain trust” did manage to do, thanks mostly to Robert McNamara and Ted Sorensen, via a nationally televised address by Teddy a week later, the content of which bore little resemblance to the facts of the Chappaquiddick incident.

This gathering at the Kennedy compound reminded me of one that had occurred there five years before, when a group of Catholic priests had strategized with the previously pro-life Kennedys about how they could, within the pro-abortion Democratic Party, have “cover” from the Church via a . . . nuanced view of the politics of infanticide – the “I’m personally opposed, but . . .” position.

I suppose it also provided the Kennedy men (and, later, some Kennedy women) with space in which they could justify serial adulteries, divorces, and remarriages, and in which they sometimes received the “blessing” of the Roman Catholic Church. The term “Kennedy annulments” fairly defines the sorry state into which the tribunal process has fallen when the rich and powerful seek what they do not deserve and are given it, despite the obvious scandal and, more importantly, the moral danger to all involved.

One cannot say that once the Kennedys made themselves amenable to adultery and abortion that Mary Jo Kopechne’s fate was sealed. Still, what’s the death of one woman set against the murders of children in the womb? When one has crossed that line, one must inevitably place personal ambition above honor and self-sacrifice.

When Teddy finally got around to running for president, which he did in 1980, hoping, one supposes, to emerge from what he often called the “shadow” of his three older brothers (Joe Jr. had been killed in WWII), it was Chappaquiddick that stood in his way. Whether or not in unseating Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter, as he had hoped to do, he would have done better against Ronald Reagan is unlikely. But the people of Massachusetts re-elected him to the Senate after Chappaquiddick in ’70, ’76, ’82, ’88, ’94, 2000, and 2006. But Mr. Curran’s riveting film is not a political polemic. It’s a portrait of personal hubris worthy of Euripides or Sophocles.

____

Chappaquiddick is rated PG-13 (for language and the scenes of Miss Kopechne’s struggle to survive) and includes fine supporting performances from Kate Mara as Mary Jo, Bruce Dern as Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., and Clancy Brown as Robert McNamara.