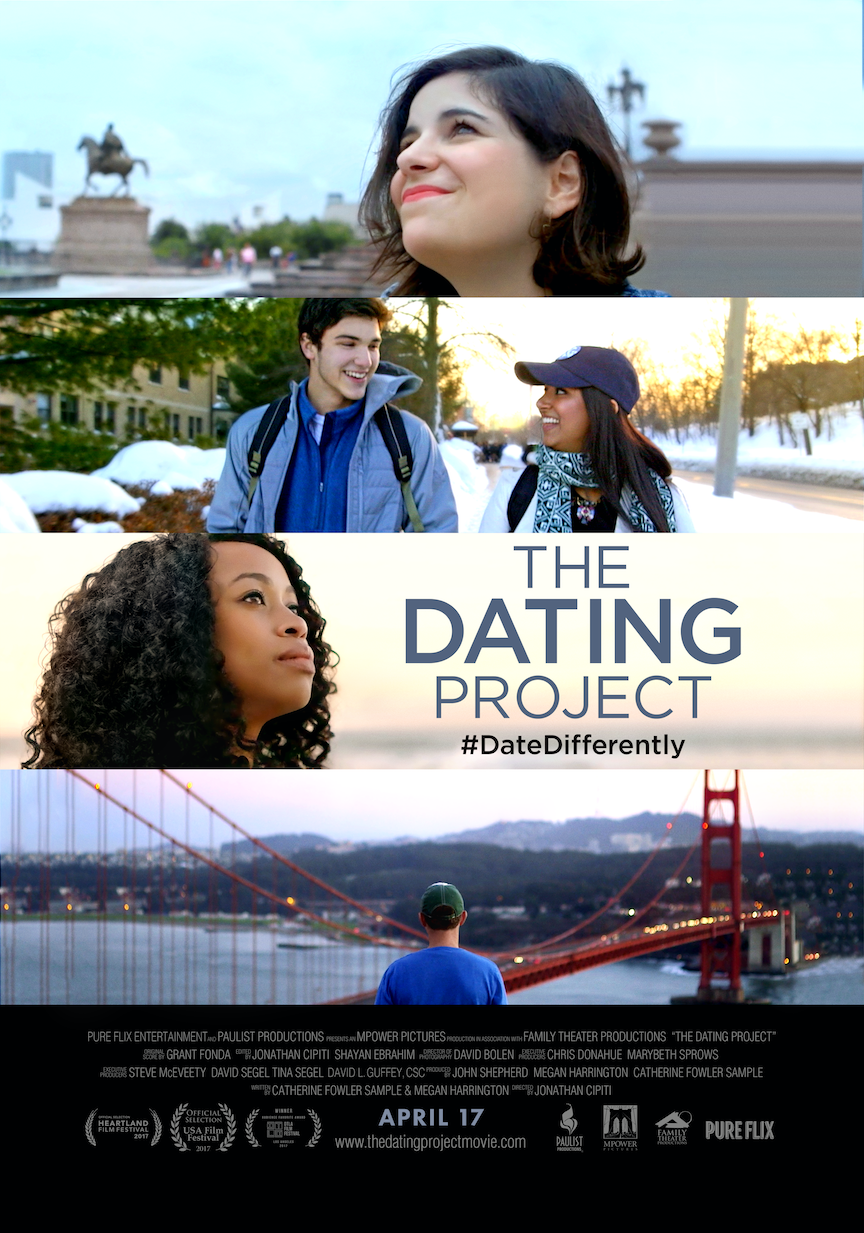

Tomorrow (4/17/18), Fathom Events (best known for short-run theatrical re-releases of classic films and for simulcasting opera live to movie theaters) will present in 750 “cinemas nationwide” a documentary directed by Jonathan Cipiti entitled The Dating Project (click on the title to find a theater in your area: I found three near me).

The film is co-produced by Paulist Productions, Mpower Pictures, and Family Theater Productions – with distribution by the aforementioned Fathom and by Pure Flix.

It seems to me a bold plan, indeed, to hope to fill seats on a spring Tuesday with folks – mostly young ones, I presume – eager to watch a film about why it is so difficult to date in 2018, which is what the film is about.

The Project began in the Boston College classroom of Professor Kerry Cronin, who teaches classics and who noticed that her students are moving romantically through their teens and twenties like so many billiard balls: having glancing collisions with the opposite sex in which the traditional subtext of marriage isn’t even part of the game. Girls go to places where they know boys will be (and vice versa), and there they may “hook up,” a dreadful phrase (and a more dreadful reality) describing everything from “Let’s go to the local ristorante for a pizza” to “Let’s go to my place and have sex.”

Professor Cronin was stunned to discover that both sexes rarely ask one another out on a date.

A weakness of The Dating Project is its failure to explain why more traditional relationships are no longer preferred; why serial, planned meetings between man and woman have been replaced by a kind of directionless spontaneity. No doubt social media have something to do with this, and yet biological realities haven’t changed.

I’m a Baby Boomer – a product of what was called the Youth Culture – so I know something about . . . casual relationships. In the time between my high-school graduation and my entrance into the Church at 24, I was, for all intents and purposes, a pagan, and yet I was never without anxiety about “sexual freedom.” And although I don’t recall his name or the book being mentioned in The Dating Project, it seemed to me as I watched the film that the best thing Professor Cronin could do is give a copy of The Confessions of St. Augustine to every one of the students who come (in large numbers) to her lectures about dating.

On second thought, though, maybe that’s not the best book, given that, in abandoning fornication, Augustine did not embrace marriage. He put aside the mother of his child in favor of the priesthood.

On second thought, though, maybe that’s not the best book, given that, in abandoning fornication, Augustine did not embrace marriage. He put aside the mother of his child in favor of the priesthood.

What’s missing in the so-called “hook-up culture” is a deep and abiding sense that fornication is immoral, and there is an eeriness in the words of one girl who says of the response of a certain boy to her sensible request to know what the heck is going on between them: he says: “We’re dating, but we’re not ‘dating’ dating.” To which she remarks to the interviewer: “I don’t know what that means.” She’s a lovely young woman. She is confused and, essentially, blames herself for the fecklessness of the young man.

Professor Cronin is leading a kind of insurgency against the sexual revolution that would be very much approved, I suspect, by Pope Francis. She is confrontational without being judgmental. She does not say to her students, as some might, “You do know if you cross the line and have pre-marital sexual intercourse that you are putting your souls at risk of eternal damnation, right?” And she may be correct, in the age of the “snowflake,” not to put the case for courting and fidelity so starkly.

It may be better simply to emphasize the risks, and not just of disease and unwanted pregnancy but also of the sundering of emotional attachments hardwired into us humans. If ever there was a phrase more epically stupid than “casual sex,” I don’t know what it is.

But how do you get young people, most especially young Catholics, to reimagine dating as courtship?

To be sure, not every courtship will end in marriage: better to get the “divorce” before the marriage. Most serious relationships – among those who very much want to marry – begin hopefully, but some will discover that the initial attraction simply doesn’t translate into long-term commitment: love may blossom then wither. But the idea that what one should conclude from this is that sexual experimentation is necessary before engagement and marriage is nothing more than a prima facie illusion.

So Cronin encourages what amount to baby steps: Look her (or him) in the eye and ask her (or him) to go out on a specified but short date: time and place.

I don’t know. To me, this seems like putting a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound, but I guess you have to start someplace. And for all I know, Professor Cronin’s lectures may be as close as some B.C. students come to learning anything about Catholic moral theology.

But I was most struck by segments in the film involving 40-year-old Christopher, oldest of the five profiled “kids,” a Californian whom one might describe as “carefree,” although only with irony. In one scene, he visits his 90-year-old mother, who makes perfect sense simply by telling the truth we’ve always known. (She’s also the most beautiful woman in the film.) Make reasonable choices, she tells her son who ought to know it already, and pray to God and follow His guidance.

And, finally, Christopher seems to get it: his problem has been selfishness. One only worries listening to him that he’s more enamored of his insight than committed to the reformation of his behavior. He seemed to me like Scrooge led by the ghost of Christmas future: he sees where he is headed, but the question remains: Will he repent before it’s too late?