Mention Flannery O’Connor’s name, and many people say they dislike her stories because they’re so bizarre, sometimes even gruesome. One story that immediately comes to mind is “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” featuring a family stranded by the roadside that meets a violent death at the hands of a murderer called the Misfit.

There’s also the unforgettable moment in “Revelation,” when a college student named Mary Grace hurls a textbook at the head of Mrs. Turpin, a deeply prejudiced woman who considers herself a good Christian.

When I was an undergraduate English major reading O’Connor’s stories, my professor delved into the shocking moments in her fiction without mentioning that this Southern writer (d. 1964) was a faithful Catholic who used violence to prepare her characters for their moment of grace. As she put it, “My subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory largely held by the devil.”

A daily communicant, O’Connor prayed the Liturgy of the Hours, defended Catholicism in her letters, and wrote book reviews for the diocesan newspaper. And she was quite fond of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, known as The Little Flower, who entered the cloister in 1888 at the age of fifteen and died nine years later.

Yet the little French nun and the outspoken Southern author shared many things. O’Connor’s descriptions of the backwoods characters in her stories had readers wiping away tears of laughter, while Thérèse entertained the nuns by doing impersonations that captured the mannerisms of other people in hilarious detail.

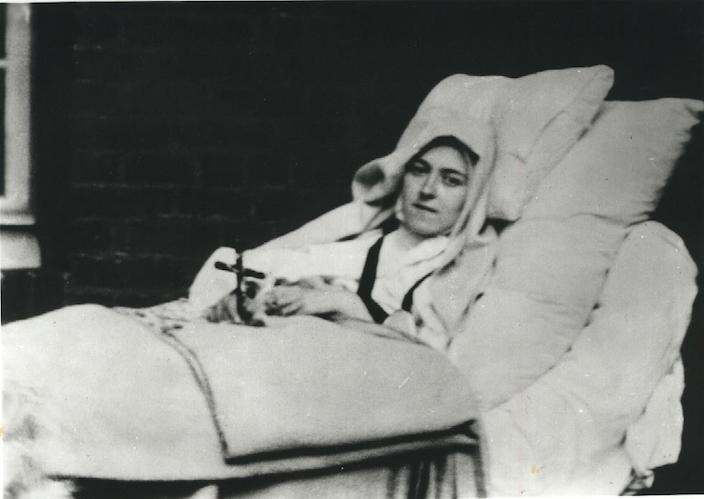

Both women struggled with terrible illnesses that severely limited their lives. O’Connor was so handicapped from the effects of lupus, which she contracted when she was twenty-five, that she said, “I can’t even kneel down to say my prayers.” Thérèse battled tuberculosis, finally succumbing to the disease after prolonged, intense suffering.

O’Connor accepted her physical restrictions as God’s will and modeled herself on Thérèse’s little way, a revolutionary path to Christ. Living as a sickly nun behind convent walls, Thérèse decided she couldn’t achieve great spiritual accomplishments, so she devised a humble path, based on Jesus saying, “Unless you turn and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.”

The little way of spiritual childhood meant making small, moment-to-moment sacrifices out of love for God. For example, there was a nun whose personality clashed sharply with Thérèse’s, but rather than reveal her feelings, Thérèse treated the woman with love – and did this so well that the woman thought she was Thérèse’s favorite.

O’Connor made her sacrifices from the confines of her room at Andalusia farm in Milledgeville, Ga., where she worked on her stories and churned out hundreds of letters, despite the exhaustion that accompanied her illness. Sometimes a single letter, crafted with compassion and concern, could encourage someone grappling with doubts about their faith.

O’Connor bristled at depictions of saints that made them seem impossibly holy and sickeningly sweet. One of these, in her opinion, was St. Thérèse, often portrayed surrounded by banks of roses and wearing a pious smile.

In 1956, O’Connor wrote a review for The Bulletin, the diocesan newspaper of Atlanta, praising a book, Two Portraits of St. Thérèse of Lisieux by Etienne Robo, for dispensing with the flowers “and other icing” and instead portraying the saint in her “very human and terrible greatness.”

She stated drily, “Those of us who have been repulsed with popular portraits of the life of St. Thérèse of Lisieux and at the same time attracted to her iron will and heroism . . . will be cheered to learn that this reaction . . . is not entirely perverse.”

Thérèse’s heroic spirit was especially shown at the end of her life when her suffering was so great she frankly admitted that, without her faith in Christ, she’d have committed suicide. She didn’t live to see the holy cards depicting her as a sweet, serene girl who seems removed from the world’s tribulations. But it’s likely she’d have agreed with O’Connor that such portrayals miss the real heart and soul of the saints.

After all, Thérèse once expressed dismay over sermons that made the Blessed Virgin Mary seem so different from ordinary human beings “that they raise her as much beyond our love as beyond our imitation.”

Thérèse’s remarkable will is shown in a passage from her autobiography, Story of a Soul, where she writes about a nun who shattered the silence in the chapel, driving Thérèse nearly to distraction by making a “funny little noise” (perhaps with her teeth), which sounded like two shells being rubbed together.

Instead of bolting from the room, Thérèse concentrated on listening to the noise as if it were music: “My entire meditation was spent in offering this concert to Jesus.”

Some Catholics hope O’Connor will follow in the footsteps of Thérèse and be declared a saint. But O’Connor herself had little patience with anyone who praised her as saintly. “I do not lead a holy life,” she stated flatly.

In this humble assessment of her life, she shares something else in common with Thérèse, who doubted she’d ever be named a saint. Thérèse confessed she found the same difference between herself and the saints as exists “between a mountain whose summit is lost in the clouds and a humble grain of sand trodden underfoot by passers-by.”

But the fact is that it is of such humble materials that great saints are made – saints both similar and quite different from one another – which should be a consolation and guide for all of us.