A man can only take so much.

Fr. Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez, among the Church’s newest saints (along with Paul VI and five others canonized today), was basically a scholarly type. In his homily upon installation as archbishop of San Salvador, the bespectacled Romero said apologetically, “I come from a world of books.” He was thought to be a church mouse, aligned with the Salvadoran establishment, and chosen to be archbishop for just that reason. He was shy and considered a moderate as, perhaps, at the start he was.

But conditions in El Salvador in 1977 were wretched and growing more so: wide gaps in income and equality, with a military ready to use extra-judicial means (i.e., “death squads”) to maintain the status quo. Barely three years into his episcopate, Romero had had enough, and the moderate was radicalized. He became the voice of a kind of revolution, although he never embraced the Marxism that had seeped into several currents of Liberation Theology.

In any case, his last, thundering Sunday sermon would lead to his death:

We want the government to face the fact that reforms are valueless if they are to be carried out stained with blood. In the name of God, in the name of this suffering people whose cries rise to heaven more loudly each day, I implore you, I beg you, I order you in the name of God: stop the repression.

He was martyred the very next day (March 24, 1980) as he said Mass in the chapel of a San Salvador cancer hospital, almost surely the victim of one of those death squads run by Roberto D’Aubuisson, who is assumed to have given the order for the assassination.

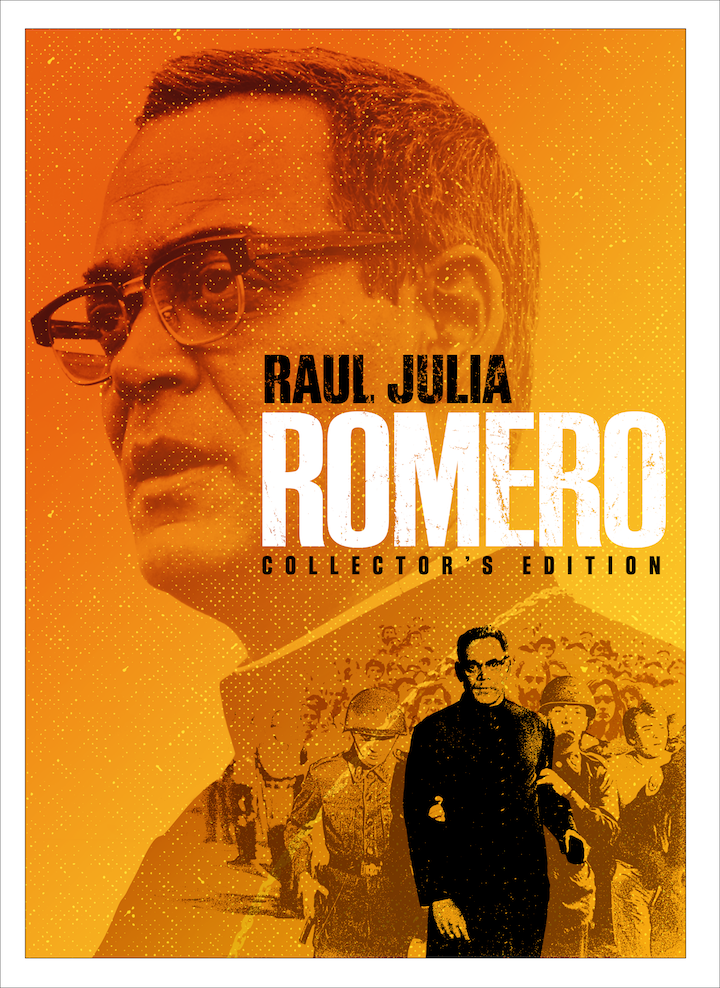

In Aussie director John Duigan’s 1989 film, Romero (now re-mastered and re-released by Paulist Productions in a “Collector’s Edition” to coincide with the canonization), D’Aubuisson is not named and is represented, in composite, by two fictional military men. Puerto Rican star Raúl Juliá plays the eponymous archbishop in an interesting, mostly restrained performance.

The late Mr. Juliá, then 48, was a dozen years younger than Archbishop Romero during the period depicted in the film and, at 6’2”, stood half-a-foot taller. Of course, such discrepancies in movies are commonplace. (Think of the 6’4” John Lithgow as the 5’6” Winston Churchill in the Netflix series The Crown, bowing to make himself smaller in relation to Claire Foy, who is the same height, 5’4”, as Queen Elizabeth II.)

But the stature of the cinematic Romero, apparently the tallest man in El Salvador, serves to make him a “towering figure,” which his sainthood suggests he was.

Romero received mixed reviews when first released, but most critics had high praise for Mr. Juliá’s performance, which I found good though understated – sometimes to the point of being soporific. I guess I agree with Vincent Canby of the New York Times who wrote that the “film’s manner is that of a textbook.” Mr. Duigan and screenwriter John Sacret Young produced a movie with mostly lifeless dialogue, jumbled scenes, cardboard characters, and predictable left-ish politics. There’s little tension as the “biopic” makes its inexorable march towards Romero’s murder.

Romero received mixed reviews when first released, but most critics had high praise for Mr. Juliá’s performance, which I found good though understated – sometimes to the point of being soporific. I guess I agree with Vincent Canby of the New York Times who wrote that the “film’s manner is that of a textbook.” Mr. Duigan and screenwriter John Sacret Young produced a movie with mostly lifeless dialogue, jumbled scenes, cardboard characters, and predictable left-ish politics. There’s little tension as the “biopic” makes its inexorable march towards Romero’s murder.

A man can only take so much foreshadowing.

But Romero has its moments. In one scene, the archbishop arrives unannounced at the hacienda of El Salvador’s president-elect. The soon-to-be el Presidente (Harold Cannon) gives them seats at a table with officials including one of the military chieftains, and interrupts Romero – as the archbishop is detailing crimes by the government against the people – to say that there is trouble on both sides and priests ought not to be involved in politics; further that he’s not going to put up with any agitation by priests, and that one murdered priest (there were many), Fr. Rutilio Grande (Richard Jordan), was a communist.

Mr. Juliá’s face barely changes from its usual placid expression. He does not look at the president-elect but says with quiet conviction: “You are a liar.” It’s Romero’s alea iacta est moment, and it’s powerful.

Later, at a bishops’ meeting, it’s clear Romero has decided not to attend el Presidente’s inauguration, and there is a shouting match between him and the bishop-military-vicar (Al Ruscio). And when anger explodes from out of Juliá’s sedate exterior, it’s arresting.

Well, at least it is the first couple of times.

Shortly thereafter, following a tense (wholly fictional) confrontation with a power-mad sergeant in a church desecrated by soldiers, a look comes over Juliá’s face. It’s still a mostly expressionless look, except his eyes display a subtle awakening: Romero realizes he will surely be murdered by these people.

My colleague Robert Royal wrote in his extraordinary 2000 book, The Catholic Martyrs of the Twentieth Century, that not long before he was assassinated Romero remarked:

“If they kill me, I shall rise again in the Salvadoran people.” In another man [Dr. Royal writes], the indirect comparison of himself with Christ might have seemed presumptuous. In Romero’s case, it was neither more nor less than the truth.

Make no mistake: Romero was a man of heroic virtue, and it’s wrong to think of him merely as a man radicalized by the turmoil of El Salvador’s class war. That would make him like Judas. But Romero was more like Jesus when our Lord drove the buyers and sellers from the temple. Romero didn’t seek liberation in the socialist sense but simple, Christian justice.

“Courage is almost a contradiction in terms,” wrote G.K. Chesterton. “It means a strong desire to live taking the form of a readiness to die.” Óscar Romero was ready to die. And his canonization – sure to be seen in many quarters as a geo-political statement – is really a tribute to courage, in no small measure because of his embrace of the Church’s “preferential option for the poor” against those who believed the poor can be ignored or saved by Marxism.

Despite its flaws, this is a film very worth watching.

___

Romero is rated PG-13 for scenes of violence. If you’re an Amazon Prime member, the film is available now. If your church would like to arrange a screening, you may do so by clicking here.