Much has been said and written about synodality recently. And the Vatican’s last-minute intervention in the meeting of the American bishops this week has raised further questions about precisely what Pope Francis means to achieve by promoting it: does it mean German bishops may decide to give Communion to the Protestant spouses of Catholics without Rome’s permission, but that American bishops cannot make decisions about how to handle the abuse crisis?

The uncertainties are built into the very notion of synodality. The term is a vague neologism and has been vaguely applied in various contexts. It can’t help generating multiple interpretations and, in the end, more confusion. It gives the impression of reducing the Church to a democratic and parliamentary enterprise – or not, depending upon how the winds are blowing in Rome.

Caution needs to be applied, especially when the term has theological-ecclesiological implications. Let me clarify at least one of its applications in Eastern Orthodoxy – a model of synodality quite different from that of the Western Church.

One of Francis’ obvious priorities since his election was and still is synodality, including the Eastern-Orthodox version. On December 3, 2013, after his election to the See of Peter, Pope Francis had a private meeting with Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

Shevchuk told the Catholic News Agency afterward that his meeting with the pontiff focused primarily on “the synodality of our Church.” The pontiff was keen on “foster[ing] the collegiality in the Catholic Church.”

Coincidentally, synodality – or better, lack of synodality – is currently making headlines in the Orthodox world, as the crisis of Ukrainian autocephaly is unfolding. There’s a tug-of-war between the Patriarchate of Russia and the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople, causing unprecedented modern divisions in Orthodoxy.

A recent Serbian-Antiochian Joint Statement calls for a synodal, pan-Orthodox solution to the Ukrainian crisis, which should involve all Orthodox Churches. This is in line with Orthodox ecclesiology of “sister churches” and Orthodox synodality, whereby the effective government belongs to the sister churches gathered and deliberating in a synodal assembly.

The Patriarch acts as primus inter pares– first among equals – with the members of the Synod, so authority and decision-making lie with the Bishops’ Synod of the sister churches and not with the Patriarchs. This includes the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, who, unlike the Roman Pontiff, has neither a primacy of power nor of jurisdiction over the local Orthodox Churches; “each of them is independent, and none is subordinate to the other.”

Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Department for External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate, harshly criticized the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople for “developing some kind of papist doctrine, papist self-identification” for his act of unilaterally (and without the consensus of the Synod of Bishops) granting autocephaly to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

What the hierarchs of these Orthodox Churches are advocating is the principle of consensus and decision-making, applying the principles of Eastern ecclesiology and canonical order, which are very different from those of the Latin Church.

If Pope Francis is entertaining the application of the Eastern-Orthodox model of synodality to the Latin Church, the Latin Church and papal primacy are heading in the wrong direction. This model does not fit the Latin Church’s structure, history, and ecclesiology.

The abstract neologism “synodality” derives from the Greek noun synodos and indicates an experience related to the Church, but most importantly a spirit of conduct in the Church and among the members of the Church as they exercise their roles in a synod-gathering.

In the Latin Church, this term mainly referred to the Diocesan Synod, as stated in the 1917 Code of Canon Law, also referred to as the Pio-Benedictine Code of Canon Law – especially canons 356-362.

After Vatican II the terms “conciliarity” and “collegiality” were introduced and used. In 1959, however, Yves Congar, in line with his scholarly studies on Catholic ecclesiology, recuperated the ancient meaning of the council and conciliarity in the life of the Church.

In Vatican II’s Lumen Gentium (chapter III, 23), the terms “collegial” and “collegiality” are used. It seems that the neologism “synodality” is strongly connected with collegiality, and the exercise of collegiality finds its emblematic expression in the Bishops’ Synod and its consultative role.

So what would synodality be in the Latin Church?

In the Latin Church, unlike in Orthodoxy, the Bishops’ Synod is under the guidance of the Roman Pontiff – and most importantly, the role of the Bishops’ Synod is consultative, not decision-making: “the body of bishops has no authority unless it is understood together with the Roman Pontiff, the successor of Peter as its head.” [LG 22]

The Roman Pontiff is primus – head, first, as he has “full, supreme and universal power over the Church.” In the Western Church, the Bishops’ Synod is a permanent council of bishops, but its functioning is not permanent; rather it is convened by the pontiff to explore specific matters facing the Church, as in the 2018 Synod on Young People, the Faith and Vocational Discernment which just concluded in October.

Pope Francis not only participated fully in the synod but also approved each of its phases and documents, exercising his primus-primacy over the synod. The Bishops’ Synod, however, serves collegiality and is a concrete realization of the communion of the local churches. John Paul II, in his Christmas discourse to the Cardinals and to the Roman Curia on December 20, 1990, twenty-five years after the Second Vatican Council, discussed the inherent connection between collegiality and primacy – and the importance of the Synod in exercising papal primacy.

If Francis indeed aims to apply a version of Eastern Orthodox synodality to the Catholic Church, this would be an ecclesiological impossibility, given the different structure, organization, and conception of the Roman Catholic Church. Synodality will, in that case, be a word without content or substance, but continuing to generate confusion and conflicting interpretations.

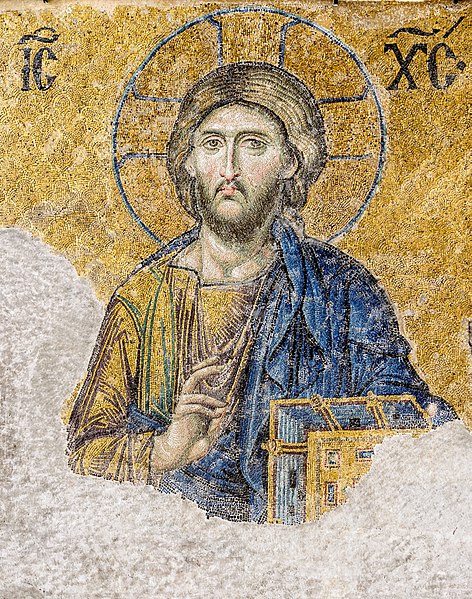

*Image: Christ Pantocrator by an unknown 13th-century artist [Hagia Sofia, Istanbul]. Hagia Sofia (“Holy Wisdom”) was built in 537 A.D. as a Greek Orthodox patriarchal cathedral, briefly became Catholic during the Fourth Crusade, then a mosque after 1453, ubtil finally becoming a museum in 1935.