Fifty-five years ago last Thursday, John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dealey Plaza, Dallas, at 12:30 pm Central Time. The anniversary passed, for me, while I was working through St. Alphonsus Liguori’s great spiritual work, The Preparation for Death. And a puzzle formed in my mind.

On the saint’s terms, JFK’s death ought to have been a great matter for reflection on the meaning of death. After all, “the death of the great prince” has traditionally served such a purpose. For example, the saint quotes Horace: “Death brings down the scepter to the level of the spade.”

He tells the story of how Diogenes was seen by Alexander the Great looking intently for something among the bones of the dead. When the conqueror asked him what he was searching for, Diogenes replied, “I am looking for the head of Philip your father. I am not able to distinguish it. If you can find it, show it to me.”

There are many such examples in the treatise.

And other tragedies have struck us in this way: not a few financiers, looking at their colleagues jumping from the flames of the Twin Towers, asked, “What if it had been me?” – and then fairly quickly made some major changes in their lives.

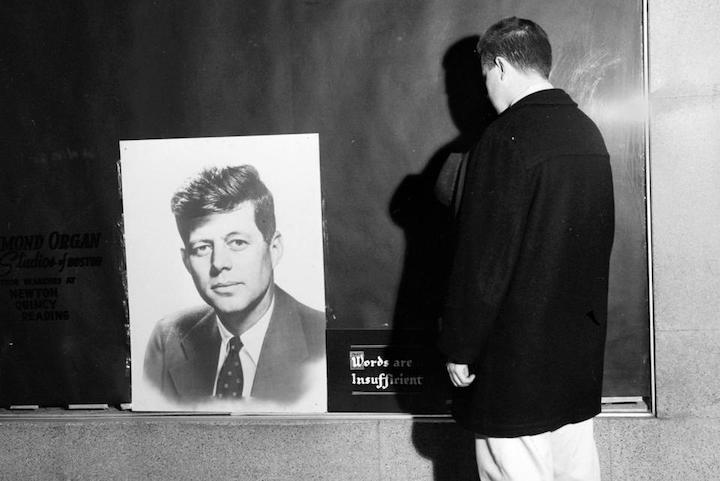

Yet JFK’s death from the start seems to have been interpreted mainly in terms of the aspiration of the nation. At the funeral Mass in St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Washington D.C., for instance, the presiding celebrant, instead of a homily, read from Kennedy’s inaugural address. Today people try to understand it by conspiracy theories, or they group it with MLK’s and RFK’s killings, seeing it as an unmasking of polite society that reveals a putative violence harbored within.

Yet it is not so difficult to ponder it with Liguori. After all, we continue to be shocked by it. Even if someone is too young to tell “where were you when you heard the news that,” the Zapruder film with its eyewitness viewpoint induces a similar feeling of shock. That shock needs to be transformed from one viewpoint, and from one kind of consideration, to another.

The president’s convertible limousine enters Dealey Plaza. It’s a sunny day and warm. He leans out smiling, admiring the families lining the street, nicely dressed, who wave jubilantly to welcome him. His wife, Jacqueline, is beside him in the vehicle, looking as beautiful and stylish as ever, wearing a lovely pink hat and matching coat. They are the Camelot couple, at the height of their success and adulation.

The winding parade through Dallas is just about at its end. In five minutes, exiting the Plaza and entering the highway, they would arrive at the Trade Mart center, for a luncheon of business leaders. After the long parade through the city, the pleasant luncheon will be something of a respite. They are looking forward to it.

A moment later he felt a pain and heaviness in his throat, and he could not speak. He lifted up his arms to fight it off, whatever it was. That would have been his last conscious moment, as the fatal bullet struck his head.

Kennedy was reasonably starting to plan a second term. He did not think he would die then, nor that day. He had no warning. Absolutely nothing about his career, prospects, plans, worries, annoyances, suggested that he would never arrive at the Trade Mart luncheon, only five minutes away. He was the most powerful man in the world, and one of the most admired – so intelligent, handsome, wealthy, and blessed by fortune in every way.

“My brother, God has already fixed the year, the month, the day, the hour, and the moment, when I and you are to leave this earth and go into eternity,” Liguori writes, “but the time is unknown to us. To exhort us to be always prepared, Jesus Christ tells us that death will come unawares, and like a thief in the night.”

I know a young mother, thirty years old, felled by a hemorrhage leaving her house. She had no medical indications or complaints; she died instantly. An aunt, middle-aged, making breakfast, never made it walking from the table to the stove. A friend’s father collapsed while on a dock, fishing, during a family vacation: he passed away while this friend, a physician, applied CPR. You doubtless know similar cases. It’s close to a certainty that at least one reader of this essay will die this very week.

The following words were spoken at Kennedy’s funeral: “There is an appointed time for everything, and a time for every affair under the heavens. A time to give birth, and a time to die.” (Eccles 3:1-2) But let us receive them not as fate, but as an invitation to pray.

The prayers for a holy death are among the most beautiful in the Church. St. Alphonsus gives us this: “My Lord Jesus Christ, by that bitterness which Thou didst endure on the cross, when Thy blessed soul was separated from Thy most sacred body, have pity on my sinful soul, when it leaves my miserable body to enter into eternity. O Mary! By that grief which thou didst experience on Calvary in seeing Jesus expire on the cross before thine eyes, obtain for me a good death, that loving Jesus and thee, my Mother, in this life, I may attain heaven, where I shall love thee for all eternity.” Amen.

Support The Catholic Thing now!