Probably the greatest discovery a Catholic, young or old, can make is how rich the Church’s tradition is, in terms of both pure thought and practical wisdom. If (taking your cues from mass media and entertainment) you think Catholicism is just a jumble of outdated rules and awful scandals, a quick look into Augustine and Aquinas and Pascal and Newman, Dante and Michelangelo and Mozart, should put that nonsense to rest.

Yes, but we know so much more than all that, someone might argue. Just look at the advances we’ve made in science, and technology, particularly medicine and psychology. All that old stuff was fine in its time, but we have much more knowledge available to help us deal with the human condition.

True, if you have a toothache or a heart problem, you’d rather be treated by a modern dentist or cardiologist than anyone in the past. But as our tradition and all good thinking tells us, in other matters, you have to be able to make careful distinctions between good and bad – and good and evil – if you want to understand anything at all.

Because it’s on the most important questions of all that we’ve gone not forward, but woefully, heedlessly, backwards. Take, as the key instance, questions about love.

At present, if you say the word “love” to someone, he will assume you’re talking about romantic love and sex, or in some quarters, LGBT and the whole psychological farrago behind it. Fr. James Martin, S.J. has argued, for example, that to call same-sex attraction “objectively disordered” is “needlessly hurtful. Saying that one of the deepest parts of a person – the part that gives and receives love – is ‘disordered’ is in itself needlessly cruel.”

But is our sexual nature the only place we give and receive love, and is sex the only or deepest kind of love? And does it trump all other loves because – well, because?

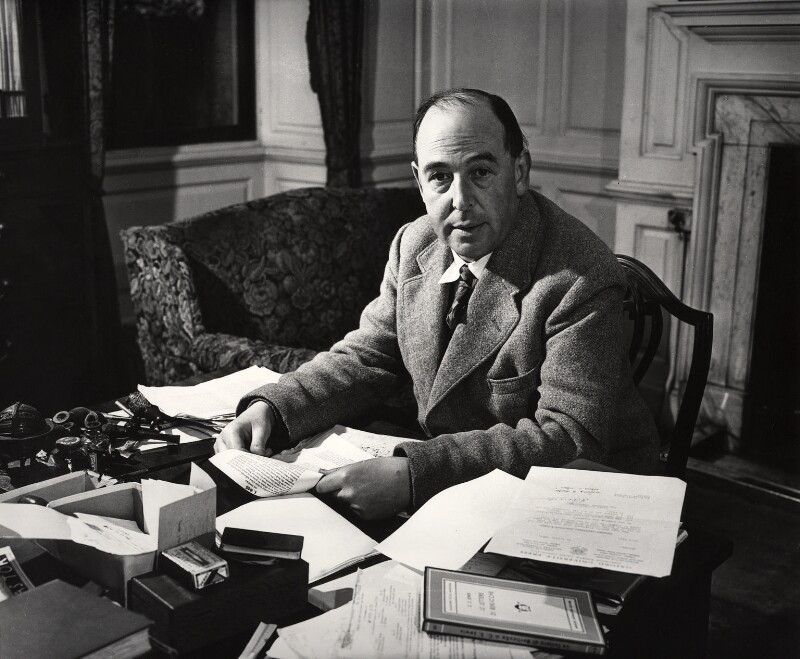

C.S. Lewis needs no introduction to serious Christians. He’s simply the best lay apologist of the last century. But many who know his great books such as Mere Christianity or The Abolition of Man or The Screwtape Letters, are unfamiliar with what may be an even more important book these days, The Four Loves.

Lewis’ four loves are not LGBT, it almost goes without saying, because in the older views of the human person erotic or sexual love – even in its deviant forms – is only one of several kinds of love. And while sex is part of God’s human creation (“male and female he created them”), we were not created solely or primarily for sex.

No mere summary of The Four Loves can do it full justice: You have to read Lewis and absorb his detailed and sensitive attention to the various kinds and manifestations of love that we humans experience to see just how rich and complex the whole subject is.

But in outline, the four loves, as he describes them are:

1) simple affection (Greek storge), such as we see between acquaintances, co-workers, and (Lewis claims) even exists between animals like cats and dogs in the same household (and is no less real for us since we, too, are partly animals);

2) friendship proper (Greek philia), which itself takes many forms, some more interested, others disinterested, in which the good of the others plays at least some role;

3) sexual love (Greek eros), with its many necessary distinctions and moral implications for family, children, community, etc.

4) charity (Greek agape), the purest of loves, the selfless concern for the other, including obedience to God, absolute and beyond our own personal interests and desires.

Just to list these is to see how reductive it is to equate love and sex and – as in so many modern contexts – to assume that sex trumps all other loves. Even in secular terms, given the troubles that unbridled eros has produced – witness most modern films, novels, television, pop songs – this is obviously and disastrously wrong.

Lewis reminds us that the loves often mix with each other. A married couple, for example, comes together and has children through eros, but will usually over time also develop affection, friendship, and even a certain mutual charity that includes their duties to the Creator.

It’s remarkable that even Christian leaders at the highest levels these days often seem oblivious to such distinctions and hierarchies. Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, for example, notoriously said after the Synod on the Family that he knew a “gay” couple in Vienna; when one got sick, the other showed him great care and concern – and that the Church must recognize the value of that.

True, in a way, but even if that care reflected affection, friendship, and charity, it could equally exist between two friends, siblings, or neighbors. It isn’t an excuse, let alone a justification, for – pace Fr. James Martin – an “objectively disordered” sexual relationship.

Neither is it “hate” to point this out. We believe in a Lord who told us there’s a way in which we must “hate” mother, father, wife, children – and ourselves also – if we want to be his disciple. His love will set our other loves in order, and make them more what they are meant to be, not obliterate them.

That an otherwise intelligent prince of the Church (and he’s hardly the only one) implied that we somehow should look past a mortally sinful relationship because of human decencies, reflects the kind of confusion that has marred a great deal of thinking – or rather, non-thinking – within the Church lately.

Lewis labored under no such delusions. He recognized that, unless our loves are ordered to great and unconditional love of God, they can become tyrannous and sometimes idols in their own right. The proof is all around us.

If we want to straighten out the manifest problems in the Church and the world at this historical moment, it’s urgent that we learn to call our loves and Love by their proper names.

*Photo: C.S. Lewis by Arthur Strong, 1947 [National Portrait Gallery, London]