If “love” and “law” seem like opposites to you – if you have the idea that one can just “love and do what you will” – then consider this popular passage:

Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. (1 Corinthians 13:4-7)

Many people admire this passage. You will often hear it at weddings, even non-Christian weddings. People hang it on posters with pictures of sunflowers. It is, admittedly, very beautiful. So let’s take a moment and think about what it means.

If we take the passage seriously, then we have to ask ourselves some revealing, and potentially troubling, questions about how “loving” we actually are. Becoming more “loving” or “being a loving person” is perhaps a bit too vague for most people. So perhaps we should make a list based on the passage and ask ourselves several more concrete personal questions.

- Was I patient today (e.g. with my mother’s requests, with my crazy uncle’s stories, when the waitress got my order wrong, or while sitting at the traffic light)?

- How kind to others was I today? How generous? Very? A little bit? Not at all?

- Was I envious or boastful or arrogant or rude? Was I all four at once?

- Did I insist on my own way – repeatedly?

- Was I irritable or resentful? A little bit (and who really even noticed)? A lot? Pretty much all day?

- Did I rejoice in wrongdoing? (e.g., Did I enjoy my bout of gossip? Was I entirely pleased with myself that I got away with cheating or lying?)

- Did I rejoice in the truth? Or is my default setting “untruth” or “my truth” or just “the things I get angry about”?

- Did I bear wrongs with understanding and forgiveness, and did I endure misfortunes gracefully, continuing to believe in God, myself, and others, and then going forth with hope? Or did I surrender to cynicism and despair, become irritable and resentful, insisting on getting things my own way, and then treat people rudely, unkindly, and impatiently when I didn’t get my way?

Do you see? If you love the sound of that passage in 1 Corinthians 13, and if you have long thought there was something very “right” or “true” about it, then consider the list and ask yourself, “How loving am I – really?”

Notice, we haven’t said, “The Church tells you that you must do x, y, and z.” (Catholics have all those rules, it is said.) Or “you are commanded by the Bible to do these things, or you will go to Hell.” (What are we, Protestants? Although to be fair, the Protestants have often helpfully reminded us that you don’t “earn” your way into heaven by good works.)

Those may all be legitimate considerations, but we have not touched upon any of them here. The question isn’t whether I or anyone else likes that passage from 1 Corinthians; the question is whether you do; and if you do, what are you willing to do – what changes are you willing to make in your life – if you think it is true?

This isn’t a question of whether you want to be “moral” or “a good Christian.” Right now, we are simply asking whether you are the person you say you want to be, and whether you are willing to become the person you say you want to become – the kind of person you say you admire. To point out that there is an “internal logic” or “inner consistency” to love is not the same thing as commanding that you act a certain way or even that you become more loving. That choice is yours.

Nor am I posing as someone who is an “expert” – as someone especially good at being loving myself. We have been guided by that beautiful passage in 1 Corinthians 13 which is widely admired by people of all faiths as a counsel of great wisdom. If it is – and many people seem to think it is – then the question we must ask is: How would these words apply in my life?

If this passage sounds like a good description of love, and if I want to be a loving person, then isn’t it important to ask whether the person described in that passage sounds anything like me? Or, to be honest, perhaps not so much?

If, upon reflection, we become aware of ways in which we have failed to love (and remember, “fail” not in the eyes of the Church, but in the sense of not meeting standards of love we ourselves affirm), then for us, the “Good News” could be that, despite these failures, there is still hope.

The Christian message is that the love that made us and the entire universe is a love so great that it entered into our fallenness and became incarnate as a human person to show us that God’s love can overcome even our lack of love. As 1 John 4 tells us, we love because God has loved us first.

A human life without selfless love of the sort described in 1 Corinthians 13 is like a sunflower without sun. It soon withers and dies. So like the sunflower, we need to keep ourselves turned towards the sun and then take that sunshine into ourselves and turn it into something beautiful.

If you think you can rejoice in wrongdoing; indulge in envy, boasting, arrogance and rudeness to others; insist always on your own way; spend your life being irritable and resentful; and repeatedly ignore the truth; and still flourish like the healthy sunflower, well, then, may I suggest you just haven’t yet understood 1 Corinthians 13:4-7.

Or love.

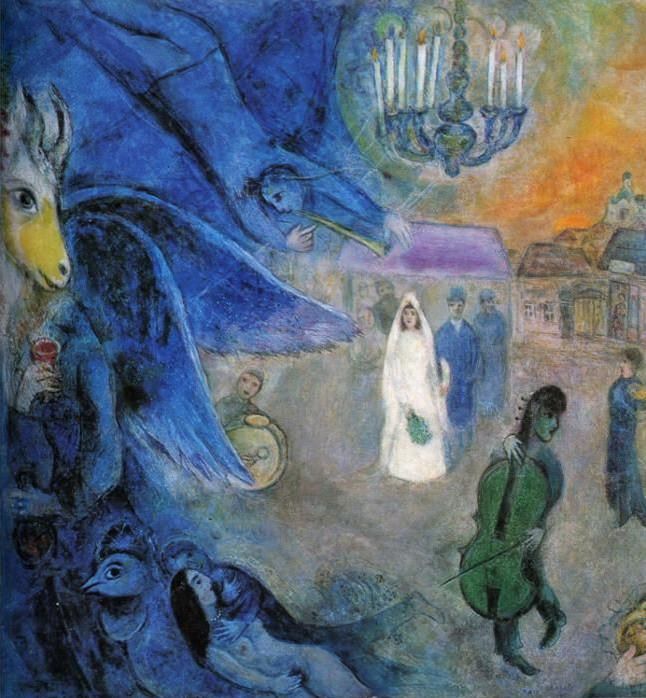

*Image: The Wedding Candles by Marc Chagall, 1945 [private collection]