Last July I made a retreat with the Trappists at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky, probably the tenth retreat I’ve made there since I first darkened the guesthouse door as an undergraduate in the 1980s. Around that time someone gave me an old paperback of The Seven Storey Mountain, the bestselling account of conversion by the abbey’s most famous monk, Thomas Merton. And I have been, despite occasional qualms, biased in Merton’s favor ever since.

After that first visit, I cut a swath through Merton’s many books, the kind of zealous reading his work provokes once the bug bites. He’s a good companion for young men with a Thoreauvian bent. Last month marked the 50thanniversary of Merton’s death, so he’s returned to my thoughts.

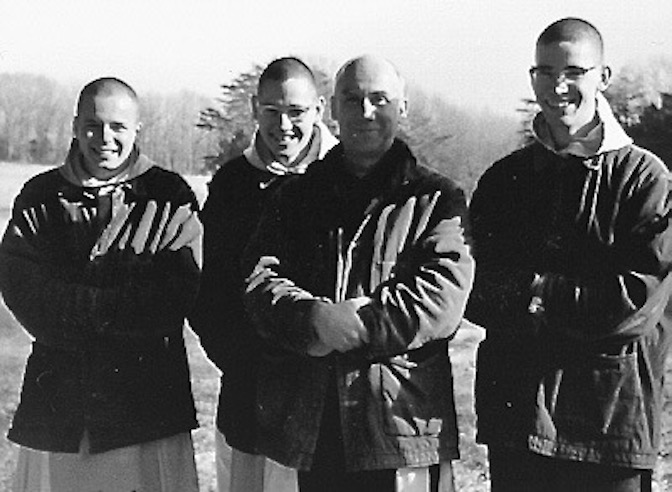

Over the years I’ve had the pleasure of knowing a monk of Gethsemani, Br. Paul Quenon, O.C.S.O., who entered the monastery fresh from high school and found himself immediately under the spiritual direction of the Master of Novices, Thomas Merton. (Imagine: a young man enters a monastery instead of going to college and ends up essentially with Thomas Merton as his teacher and advisor.)

Anybody wishing to know what Merton was like to live with during those years (1958-68) can now find some richly illuminating anecdotes in Brother Paul’s fertile memoir, In Praise of the Useless Life: A Monk’s Memoir. For Br. Paul, like his old novice master, is a well-published poet whose lyrical talent informs his prose. (The best volume for sampling his work is Unquiet Vigil: New and Selected Poems.

I often wondered what Merton would have been like to speak with, how he would have modulated his voice or driven home a point. I wondered how he would have lectured to the monks. Formally? Casually?

But a few years ago Br. Paul reminded me that many of Merton’s talks delivered at Gethsemani (called conferences) had been routinely recorded on an old reel tape recorder from around 1962 until the year of Merton’s final trip to Asia. And it was Br. Paul himself who often pressed the record button.

Those tapes reside at Bellarmine University in Louisville, which also houses the Thomas Merton Center. And now a firm called “Now You Know Media” has released on compact disc many of Merton’s talks on everything from the nature of monastic vows to mystical theology to contemplative prayer to modern and contemporary literature.

These talks open a clear window on Merton the teacher. And one thing we see is that, however edgy and occasionally heterodox Merton might have made himself in some of his published writings, when he spoke to the monks of high and consequential things, he hugged the shore a good deal more than might be supposed by his critics. He relished detail – names, dates, ideas fleshed out. He preferred that the monks know something and not be satisfied with a few scraps of minimal information on any one topic.

Nonetheless, anybody should be warned that these talks, even when strung together by themes – a series on the Latin Fathers or the Twelve Degrees of Humility or poetry or Faulkner, for instance – aren’t “courses” in any systematic sense. Merton was too digressive, too ready to amble up interesting by-ways on route to a larger point. But that’s what makes the talks valuable and, more often than not, pleasantly diverting. Some people are interesting simply when holding forth about anything.

One nicely surprising discovery for me was prompted by a passing remark of Br. Paul who revealed a point once made by Fr. Louis (as Merton was known within the monastery) during those heady days when the Vatican II was still meeting in Rome. St. Thomas Aquinas, Merton said, was a theologian read by almost no one anymore, so far had he fallen out of favor – which fact, Merton said, gave the monks a splendid reason for reading him.

A small set of talks on “The Ways of God,” a work attributed to Aquinas, reveals that Merton, even during the 1960s, retained a keen respect for St. Thomas and the Scholastics generally. A welcome find and not one Merton’s detractors would naturally suspect. And there are others. (He sometimes quotes Latin freely, often without translating but charitably boiling down the sense.)

There’s also, notably, a good deal of laughter. Merton could be silly. He knew how to crack a joke – often at his own expense and to warm appreciation; his was not the demeanor of a man taking himself too seriously. And he could be prophetic even about small things: he once opined off-the-cuff that the music of the Beatles would probably be considered quite good in fifty years, and as we know, fifty years later, he was right.

But whatever his topic, be it time or eternity, Merton was always out to help the monks see the small blue flame of significance burning low in any image or set of words: Mark this and mark it well – don’t neglect what’s here at the center. Any teacher can learn from his method.

It’s always agreeable to step away from any stereotype. Sure, Merton was more a free thinker and loose talker than centuries of the Cistercian and Trappist traditions encouraged or even countenanced, and that trait got him in the soup once in a while. But I find I never finish listening to any talk without imagining what the news of Thomas Merton’s death in far-off Bangkok on a cold day in December 1968 must have felt like to those still faithfully keeping the Hours back in the monastery, who had known and loved and learned from him for so long.